Bird flu could become deadlier if it mixes with seasonal flu viruses, experts warn

As of now, 17 states have reported H5N1 bird flu cases in humans, but there is still no evidence for transmission between people and the infections have been mild. Could that change?

Bird flu appears to be rising in the U.S., but only among people exposed to infected animals — namely, cows and poultry.

Since April 2024, the U.S. has seen 36 human cases of H5N1 bird flu across 17 states. That includes 16 cases in California, seven of which were diagnosed in the week ending Oct. 20. That same week, six workers at a Washington egg farm were also diagnosed.

Although more and more cases are being reported, officials have not yet found any examples of the virus spreading between people. Experts told Live Science that H5N1 remains a low-level concern until it does so.

There was a scare when a hospitalized patient in Missouri was diagnosed with H5N1 in August, and health care workers treating them developed similar symptoms. However, tests by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that none of the clinicians actually caught the virus, ruling out person-to-person spread. The CDC reiterated that the risk to people who don't have contact with potentially infected animals remains low.

However, the continued spread of H5N1 has raised some questions: Could the germ become deadlier? Could it start spreading between people? And how would we know?

Related: Scientists find secret 'back door' flu viruses use to enter cells

Could the virus become deadlier?

Since the first H5N1 case in April, infections in the U.S. have occurred mostly among dairy or poultry farmworkers, all of whom have experienced mild symptoms, such as eye redness or cough. At a CDC news conference held Oct. 24, Eric Deeble of the U.S. Department of Agriculture said that eye symptoms could be caused by feathers or other virus-laden matter getting into workers' eyes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Historically, human H5N1 infections have been much more severe. Between the virus's discovery in 1997 and June 2024, more than 900 people caught the infection, and just over half died. Egypt, China and Cambodia have reported the most cases, overall.

This year, Cambodia has reported 10 cases of H5N1, two of which were fatal. Vasso Apostolopoulos, an immunologist at RMIT University in Australia, explained in an email that the H5N1 virus in Cambodia belongs to a different branch of the influenza family tree. Genetic differences may account for why the virus is more virulent, causing deadlier disease, she suggested.

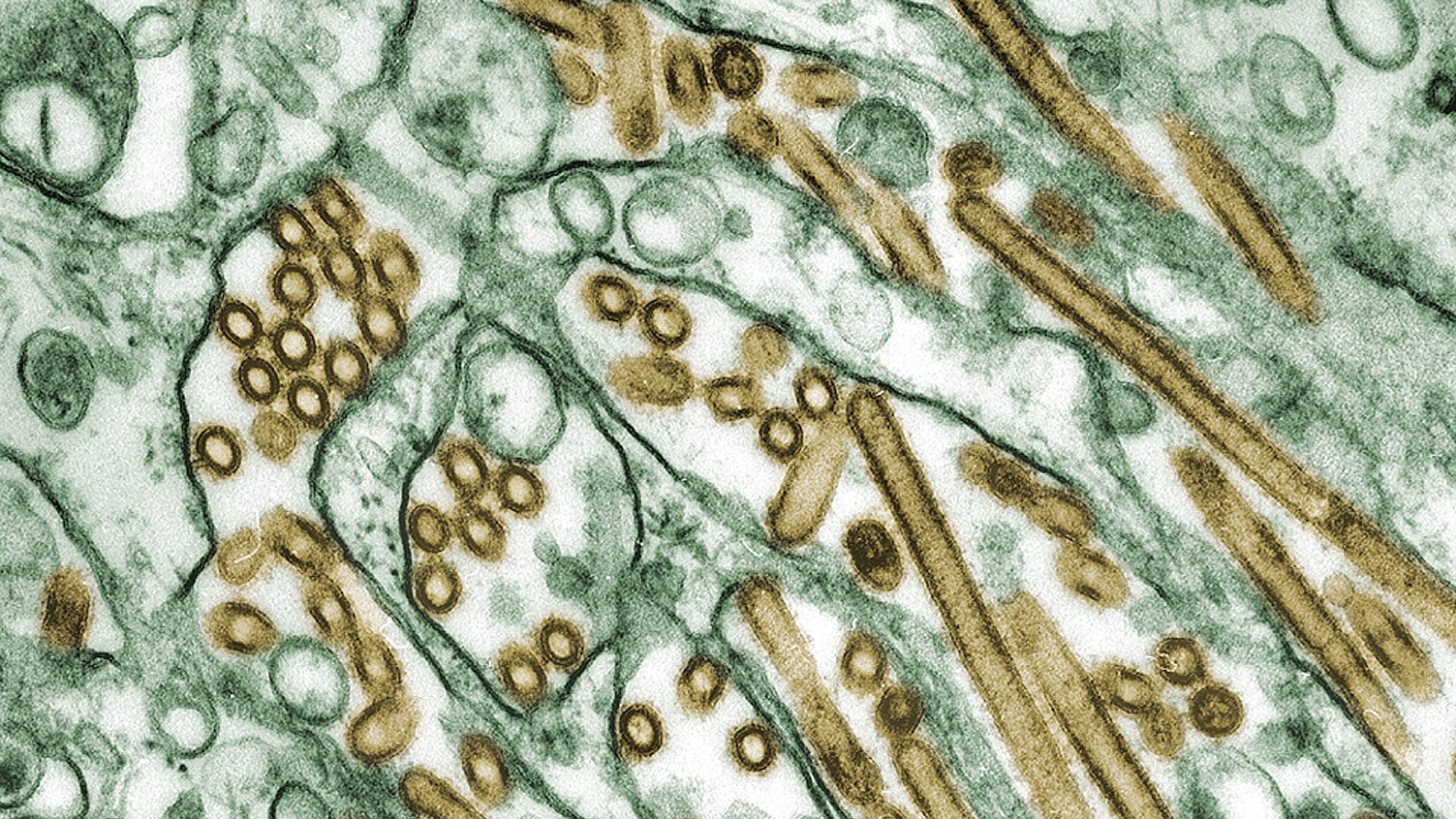

One study found mutations in several genes that may boost the virus's virulence, including a gene that codes for hemagglutinin, a protein that helps the virus enter cells, and a gene for a protein that helps the virus replicate.

The H5N1 strain in the U.S. appears less severe, but "there are still too few human cases to draw definitive conclusions about its virulence," Francesco Branda, an epidemiologist at the Campus Bio-Medico University of Rome, told Live Science in an email. Most of the U.S. cases involve able-bodied farm employees, so it's unclear whether older adults or people with other medical conditions would also show mild symptoms.

Genomes from H5N1 samples from six of the California cases suggest there are no new mutations that could theoretically worsen the infection. "However, it should be remembered that influenza viruses are known for their ability to mutate rapidly, so this may change with time," Branda said.

One concerning possibility is reassortment: If multiple strains of influenza infect the same person, they can mix and match segments of their DNA, producing a brand-new strain. As the U.S. enters flu season, reassortment could occur in farm workers who get infected with seasonal flu and H5N1 at the same time, Apostolopoulos argued. This could lead to "the emergence of a new, highly virulent strain, potentially resulting in an outbreak or pandemic," she said.

Reassortment gave rise to the virus behind the 2009 swine flu pandemic.

Related: Increased evidence that we should be alert': H5N1 bird flu is adapting to mammals in 'new ways'

Could we be missing cases?

Public health laboratories are testing for H5N1 in people exposed to infected animals, such as cows and birds, and people who test positive for flu but negative for seasonal flu varieties, like the Missouri patient. The CDC has then been following up on any positive test results with confirmatory tests.

As flu season begins, though, local labs could experience an uptick in regular flu testing. "Saturation of laboratories and health systems due to seasonal influenza cases could delay diagnosis and response to H5N1 outbreaks," Branda said.

Public health agencies could do more to control the outbreak, experts say.

"I would like to see mandatory testing of animals in all farms from affected states, increased testing of humans in contact with affected animals, and broader surveillance testing across the country," Diego Diel, a Cornell University virologist who studies viral infections in animals, told Live Science in an email.

As of now, testing of both animals and people has been patchy. Boosting surveillance will require the cooperation of farm owners, some of whom have refused to test their employees for bird flu, KFF reported, potentially because time that sick workers take off after diagnosis would lower their output. Diagnosed workers may also not get paid during their time off, meaning getting tested could come at a cost.

Update on the Missouri case

The Missouri patient raised alarm bells because they said they'd had no exposure to infected animals, raising the possibility that they could have caught H5N1 from another person.

However, it's still "likely exposure was an animal or animal product that we have not identified," Demetre Daskalakis, director of the CDC's National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said at the news conference. Domestic cats, wild birds and unpasteurized milk are potential routes of exposure that can't be ruled out.

Then, when six health care workers caring for the patient developed possible symptoms, it was suggested that person-to-person transmission might have occurred.

Related: Flu shots have changed this year — here's why

One health care worker tested negative for flu during their illness, but the others were not tested while they were sick. On Sept. 27, after the five remaining health care workers had recovered, the CDC said that it would test their blood for antibodies that would evidence a recent H5N1 infection.

The body typically makes antibodies against proteins on a virus's surface — hemagglutinin, in the case of influenza. However, after analyzing the genome of the virus from the Missouri patient, the CDC discovered some mutations in the hemagglutinin protein that differ from the version they use in standard H5N1 tests.

These mutations may change the shape of the hemagglutinin and, thus, the antibodies that bind to it. This difference might render the CDC's standard tests unsuitable, so the agency spent three weeks developing new antibody tests based on the mutant protein.

On Oct. 24, they announced the results of the health care workers' blood tests, finding that none carried H5N1 antibodies. This suggests their symptoms had other causes and that no person-to-person spread of the virus took place.

Questions remain as to whether the CDC will repeatedly need to design new tests each time the hemagglutinin gene mutates — which could delay them in flagging whether H5N1 has started spreading between people.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Oct. 31 to correct Vasso Apostolopoulos' affiliation. The article was originally published on Oct. 30.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Kamal Nahas is a freelance contributor based in Oxford, U.K. His work has appeared in New Scientist, Science and The Scientist, among other outlets, and he mainly covers research on evolution, health and technology. He holds a PhD in pathology from the University of Cambridge and a master's degree in immunology from the University of Oxford. He currently works as a microscopist at the Diamond Light Source, the U.K.'s synchrotron. When he's not writing, you can find him hunting for fossils on the Jurassic Coast.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents