'Brain-eating' infections could become more common, scientists warn

Researchers think climate change will soon cause an increase in the incidence of Naegleria fowleri infections, a "brain-eating" disease.

2023 was the hottest summer in the past 2,000 years, and summer 2024 is looking to be just as intense. As summer peaks, freshwater lakes and pools all over the United States will likely be filled with people trying to cool off. But as the temperatures of these freshwater environments rise, the organisms that live in them can shift, posing harmful, or even lethal, threats to swimmers.

Naegleria fowleri is one such threat that seems primed to start infecting more people — but surprisingly, it hasn't done so yet.

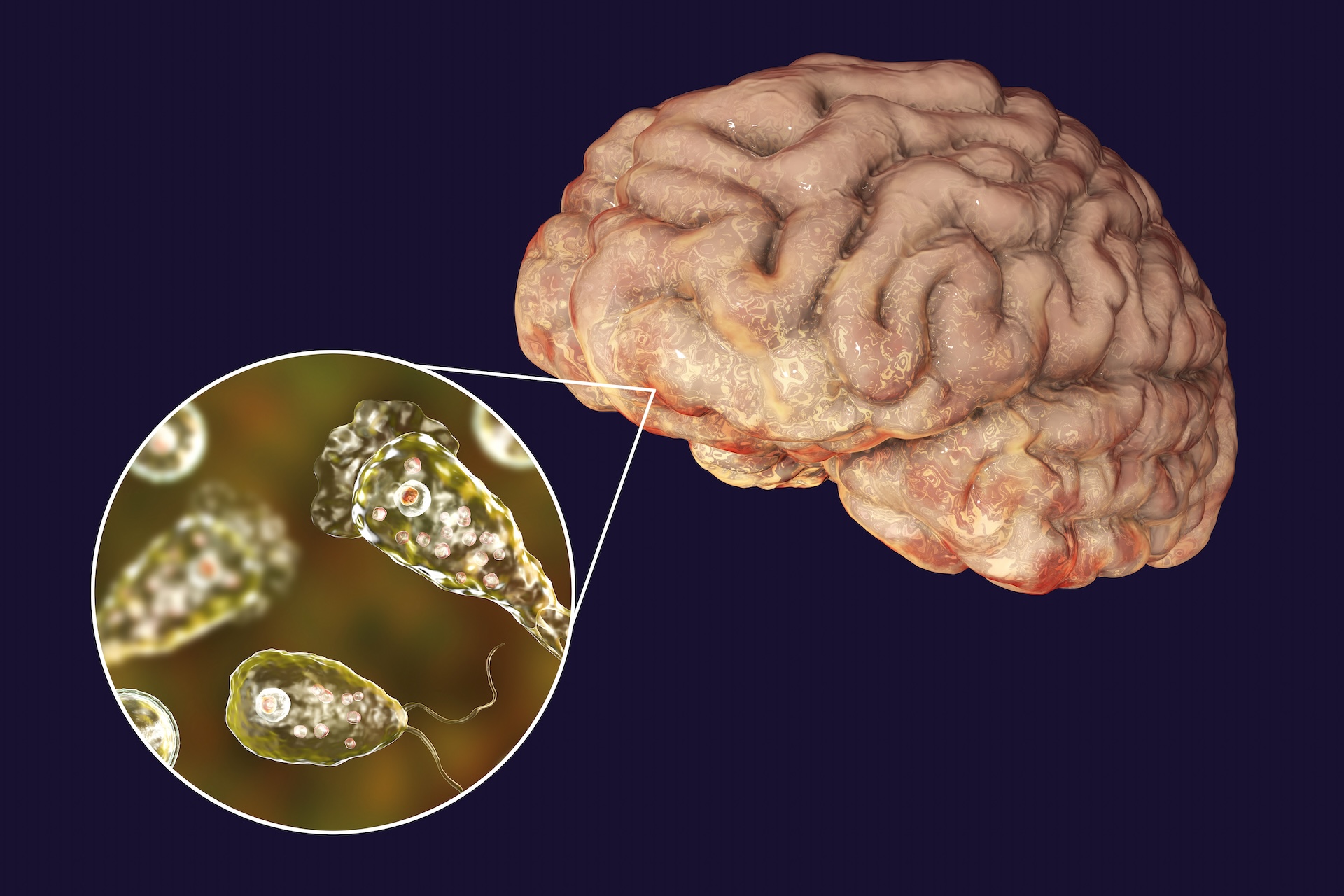

N. fowleri is a single-celled organism that loves warm temperatures, lives in soil and fresh water, and preys on bacteria, much like many others of its kind. The amoeba can lurk in lakes, rivers, hot springs, well water, tap water and poorly maintained swimming pools, among other water sources.

What's harrowing about this tiny organism is that it can enter the brain via nerves in the nose and then decimate brain cells. This rare infection can lead to a fatal condition called primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), which is why N. fowleri is commonly known as a "brain eating amoeba."

Related: Rare 'brain-eating' amoeba infection behind death of 2-year-old in Nevada

N. fowleri infections that lead to PAM are relatively rare in the U.S., averaging about zero to eight laboratory-confirmed cases per year. Although all incidents of PAM are caused by an N. fowleri infection, this fatal disorder can sometimes be misdiagnosed as other, more-common infections of the nervous system, such as bacterial meningitis and viral encephalitis. Such misdiagnoses may mean that some cases of PAM are missed.

Symptoms of PAM typically start one to 12 days after a person is exposed to the amoeba, and patients die within one to 18 days of symptoms starting. Testing for an N. fowleri infection is also a slow process, further complicating diagnosis, and there are no specific drugs to kill the amoeba.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Historically, diagnosed N. fowleri infections have been concentrated in warmer, Southern states. In recent years, however, the amoeba has been detected — and even caused infections — farther north, including in Iowa, Nebraska and Minnesota. The reason behind this is climate change.

The infections seen in northern latitudes have researchers worried that warming temperatures could make N. fowleri infections more common.

Leigha Stahl, a faculty member at the University of Alabama, recently published work on determining how changes in the environment affect the growth of N. fowleri populations. Stahl found that N. fowleri can withstand high temperature changes that other waterborne microorganisms cannot. This resilience means the amoeba can outlive its competition and thus increase its access to resources.

According to Stahl, the amoeba can survive at a range of temperatures and acidity levels. It can grow in temperatures up to 115 degrees Fahrenheit (46 degrees Celsius) but has also been known to proliferate in temperatures as low as 80 F (26 C).

"It can definitely thrive in a variety of different environments," Stahl told Live Science. As the temperatures in U.S. lakes and rivers increase — either from the overall warming of the planet or thermal pollution from manufacturers that use the water as a coolant — this fosters a more suitable environment for N. fowleri to flourish, she said.

Warming temperatures are not the only thing that could spur the spread of N. fowleri, however. Stronger and more frequent storms due to climate change can cause local changes in water levels and increase the amount of organic matter that ends up in the water from runoff. This runoff can provide nutrients to organisms in the water, including brain eaters. Storms could not only spread more N. fowleri from land to water but also change the levels of other aquatic microorganisms.

Related: Fatal 'brain-eating' amoeba successfully treated with repurposed UTI drug

"What you might see is spikes in these organisms after an extreme weather event," said Charles Gerba, a professor of microbiology and public health at the University of Arizona. "So the more nutrients in the water, the more bacteria you'll get," Gerba told Live Science.

"You could have less dissolved oxygen … more blooms of different things … maybe a greater proliferation of bacteria," Stahl added. "And if there's a greater amount of prey sources in the water, maybe that would allow the N. fowleri to eat more or be happier."

'Brain-eating' amoeba infections are nearly always fatal. But could new treatments change that?

Read more:

—This is what it's like to treat a 'brain-eating' amoeba infection

Already, massive changes in our freshwater sources have coincided with increases in the detection of N. fowleri in both Southern and Northern latitudes. And yet, paradoxically, there has yet to be a significant uptick in confirmed brain-eating amoeba infections. We're still seeing about one to two a year — but why?

The previously mentioned difficulties in diagnosing N. fowleri infection could be a factor, meaning cases might just be going unreported. Plus, Gerba said he believes it goes underdiagnosed for other reasons, particularly in northern areas.

"We're seeing it creeping up to states further and further north all the time," Gerba said. "Somebody in Minnesota or Michigan doesn't even consider that as a potential case of infection when they see it, so that's probably how they're being missed."

Evidence backs the idea that PAM cases can go underreported due to a lack of expertise among medical staff about the very rare condition, as well as the fact that autopsies are not always carried out on deceased patients.

In addition to getting more cases up north, as summertime temperatures stick around for longer, "the time period when you'll find N. fowleri will increase," Gerba said. With cases of N. fowleri infections on the rise in other countries, experts are urging U.S. clinicians to become more aware of the signs and inform more of the public about these brain-eating amoebas.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Jennifer Zieba earned her PhD in human genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is currently a project scientist in the orthopedic surgery department at UCLA where she works on identifying mutations and possible treatments for rare genetic musculoskeletal disorders. Jen enjoys teaching and communicating complex scientific concepts to a wide audience and is a freelance writer for multiple online publications.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents