Deadly amoeba brain infection can result from unsafe nasal rinsing, CDC warns

A CDC report describes 10 patients infected by an amoeba after conducting a nasal rinse, three of whom died from a nervous-system infection.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued a new report that highlights a potential danger of nasal rinsing with unsterile tap water: amoeba infections of the skin, eyes, lungs or brain.

In the report, published Tuesday (March 12) in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, the agency detailed the cases of 10 U.S. patients who were infected with a type of amoeba called Acanthamoeba between 1994 and 2022. Nine of the cases occurred in the past decade. All of the patients had rinsed out their nasal passages, most with devices like squeeze bottles or neti pots, before falling ill. They did so for various reasons, including to relieve symptoms of chronic sinusitis, or sinus inflammation.

The patients experienced a range of health complications as a result of their amoeba infections. Six people developed skin diseases, and six experienced a rare nervous system infection called granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE), which affects the brain and spinal cord. Of the 10 people who were infected, seven survived their illnesses and three of the people with GAE died.

All of the infected patients had weakened immune systems, most commonly because they had cancer and were undergoing treatment. Of the five people who reported what kind of water they had used for nasal rinsing, four said they used tap water and one said they'd used sterile water but also submerged their device in tap water.

Related: 'Brain-eating' amoebas are a new concern in northern US states, health officials advise

Tap water typically contains small amounts of microbes that are usually killed by the acid in the stomach. However, these microorganisms can survive in the nose and cause infections if they end up in there. Nasal rinsing with unsterile tap water has previously been linked to a variety of amoeba infections, such as those caused by the brain-eating amoebas Naegleria fowleri and Balamuthia mandrillaris.

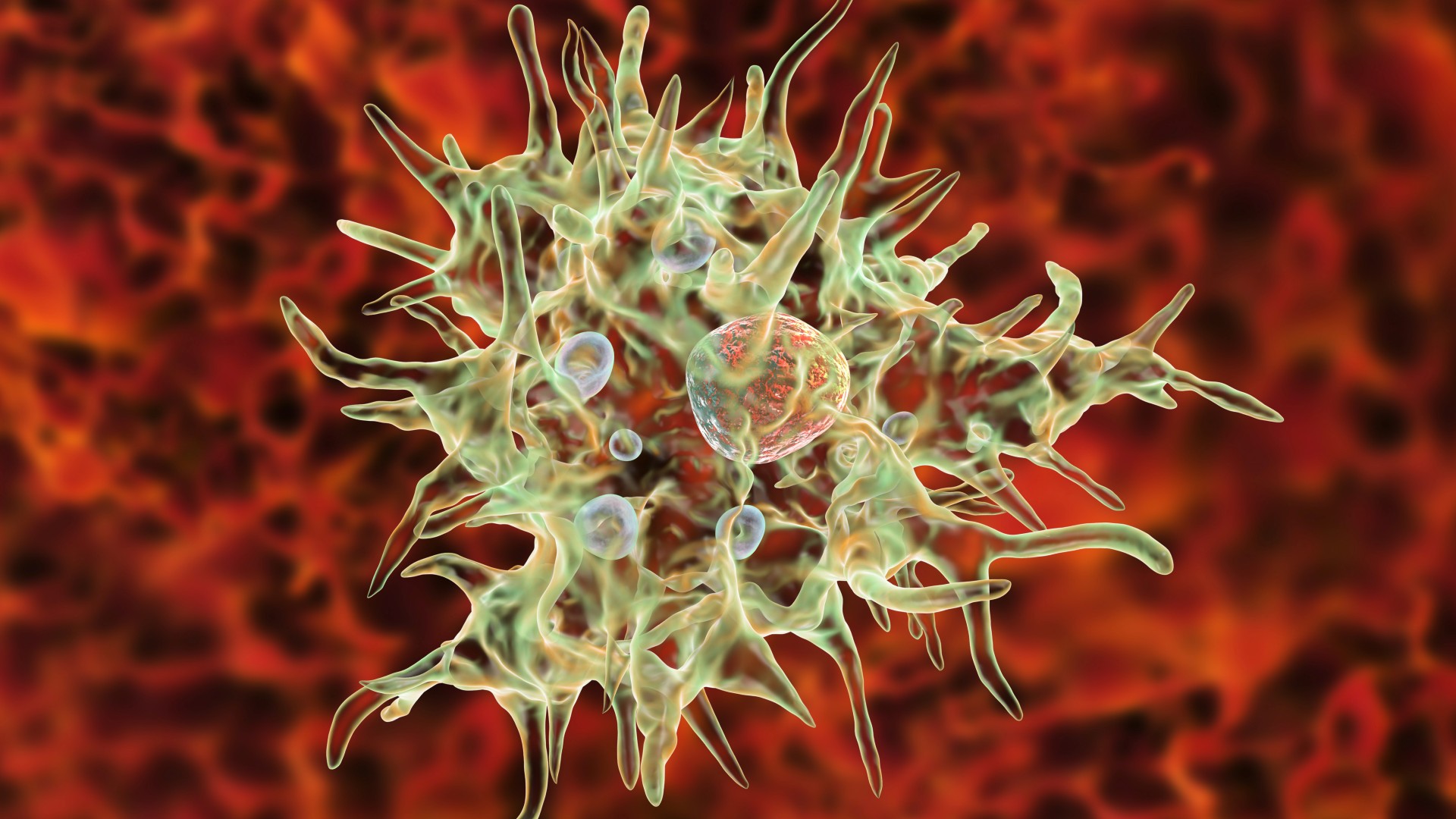

Acanthamoeba amoebas can also cause a life-threatening, brain-damaging disease, that being GAE, which starts with symptoms of confusion, headaches and seizures. The amoebas are found worldwide and live in both soil and bodies of water, including in lakes, rivers and tap water.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings of the new CDC report therefore serve as a reminder to those who practice nasal rinsing to do so safely. The CDC recommends that anyone who conducts nasal rinsing use boiled, sterile or distilled water. Tap water, for instance, should be boiled for at least one minute to sterilize it, or for three minutes if you are located above 6,500 feet (2,000 meters). It should always be cooled before use.

"We published this study because we want people to be aware of this risk," Dr. Julia Haston, senior study author and a physician and medical epidemiologist at the CDC, told CBS News.

Acanthamoeba can enter the body in numerous ways, including through the eyes, broken skin or the respiratory tract. It is a type of opportunistic pathogen, meaning it doesn't normally harm healthy people but can seize the opportunity if someone has a weakened immune system or if it can enter the body through damaged tissue. People who are most at risk of infection are those who have had an organ transplant, cancer, HIV or diabetes.

Acanthamoeba are found everywhere, so it is often hard to determine how a person may become infected or to identify ways to prevent infection, the authors acknowledged in the report. As such, with the data they have, they cannot confirm that all 10 of the highlighted individuals became infected from unsterile tap water.

Nevertheless, the authors stressed the need for increased awareness of the importance of safe nasal rinsing, which, if done safely, has several health benefits, such as relieving symptoms of allergies or colds.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents