Did pandemic lockdowns stunt kids' immune systems long-term?

Common illnesses spiked in kids as COVID-related social distancing policies were lifted. But experts say this doesn't reflect a long-term change in children's immune systems.

The COVID-19 pandemic drastically reduced people's in-person interactions with others as events were canceled and people limited their excursions, and many also practiced social distancing and masked up if they did go out. These moves were intended to control the spread of the disease and were shown to help flatten the curve.

However, some concerns have been raised about the potential impact of these actions on children's immune systems, and namely, kids' ability to fight infections. But did COVID "lockdowns" and other pandemic-related restrictions actually stunt kids' immune systems?

On that front, parents should not fear, experts told Live Science. Social distancing did not permanently stunt children's immune systems. Rather, it just delayed young children's exposure to various germs.

"During the COVID lockdown, our children were exposed to far fewer pathogens than they typically are in a normal year," Dr. Sarah Nicholas, an assistant professor of pediatrics-allergy and immunology at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, told Live Science.

Related: Master regulator of inflammation found — and it's in the brain stem

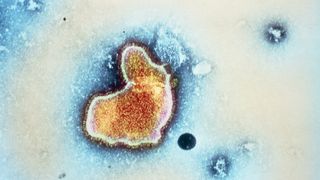

Examples of common respiratory viruses that children may be exposed to include respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); the flu, or influenza; and human metapneumovirus, as well as various viruses that cause the common cold. After such an infection, the body builds up its immune defenses so that it can tackle these pathogens if it encounters the same ones again.

Social distancing reduced not only the spread of COVID-19 but also that of other respiratory viruses, which tend to spread in similar ways. When these restrictions were lifted, the viruses were free to circulate in the population again. In addition, viruses responsible for causing other types of disease, such as viral gastroenteritis or stomach flu, also began spreading again.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As social distancing behavior waned, toddlers who had never caught these viruses were suddenly playing "catch-up" with their immune systems, Dr. James Antoon, an assistant professor of pediatrics at Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt in Tennessee, told Live Science. Consequently, many children became sick at the same time, leading to a surge in hospitalizations, he said.

In the spring and summer of 2021, there was an unusual surge in RSV cases in the U.S.; the virus's transmission normally peaks in the winter. There was also a particularly large spike in cases of RSV between 2022 and 2023 that inundated many hospitals in the country.

Although this resurgence was notable, several studies suggest that the severity of children's illnesses did not rise as COVID-19 restrictions relaxed. In other words, although case numbers rose, on a whole, children were no less able to combat these infections than kids their age had been before the pandemic.

And while social distancing reduced children's exposure to germs, most children likely still underwent routine vaccination regimens during the pandemic, Dr. Janko Nikolich, a professor of immunobiology at the University of Arizona, told Live Science. These vaccines help prime children's immune systems against many major pathogens that are harmful to their age group. Thus, their immunity would be ready for action as social distancing eased.

Notably, though, there was a dip in children's routine vaccinations during the pandemic, and many are still catching up to this day.

"We know that with COVID and with flu that vaccination is absolutely the best way to prevent poor outcomes, hospitalization and complications from these viruses," Antoon said. "So if your child is eligible for some of these vaccines, it's advantageous to get them."

Parents should know that children's immune systems are generally robust, regardless of whether they lived through pandemic lockdowns, Dr. Dean Blumberg, chief of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at UC Davis Health, told Live Science. "The difference is that there were atypical patterns of exposure and infection" during and immediately after the pandemic, he said.

"We're hopeful that kids are caught up now and going forward we shouldn't see these atypical patterns of infection," he said.

Importantly, the pandemic highlighted the impact that basic public health measures can have in preventing the spread of harmful viruses, Antoon said. In daily practice, such measures can include staying home, social distancing and masking when you're sick.

"Those are measures that are really easy to do and we can continue moving forward in a reasonable way," he said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking journalism training. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)