Drug makes blood toxic to malaria-spreading mosquitoes

Nitisinone, a drug that is already used to treat two genetic diseases, could be repurposed to control the spread of malaria, according to new research.

A drug approved to treat rare genetic diseases can also make human blood toxic to the mosquitoes that spread malaria, a new study finds.

The drug, called nitisinone, is currently used to treat two genetic conditions: tyrosinemia type 1 and alkaptonuria. The drug works by inhibiting an enzyme called 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD), which is involved in a chain of chemical reactions known as the tyrosine detoxification pathway. By blocking the enzyme, nitisinone prevents the accumulation of harmful chemicals in the bodies of patients with these genetic conditions.

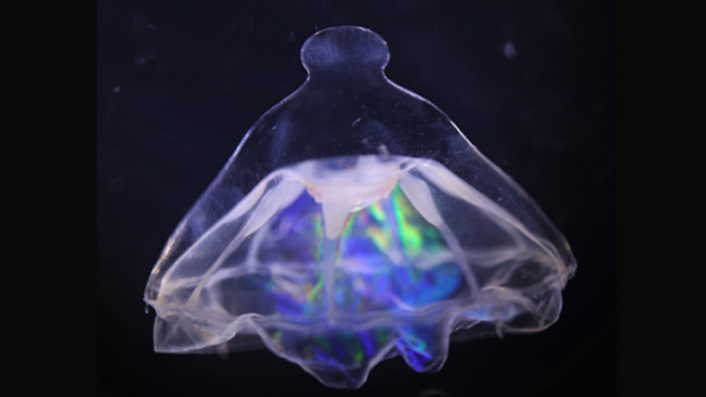

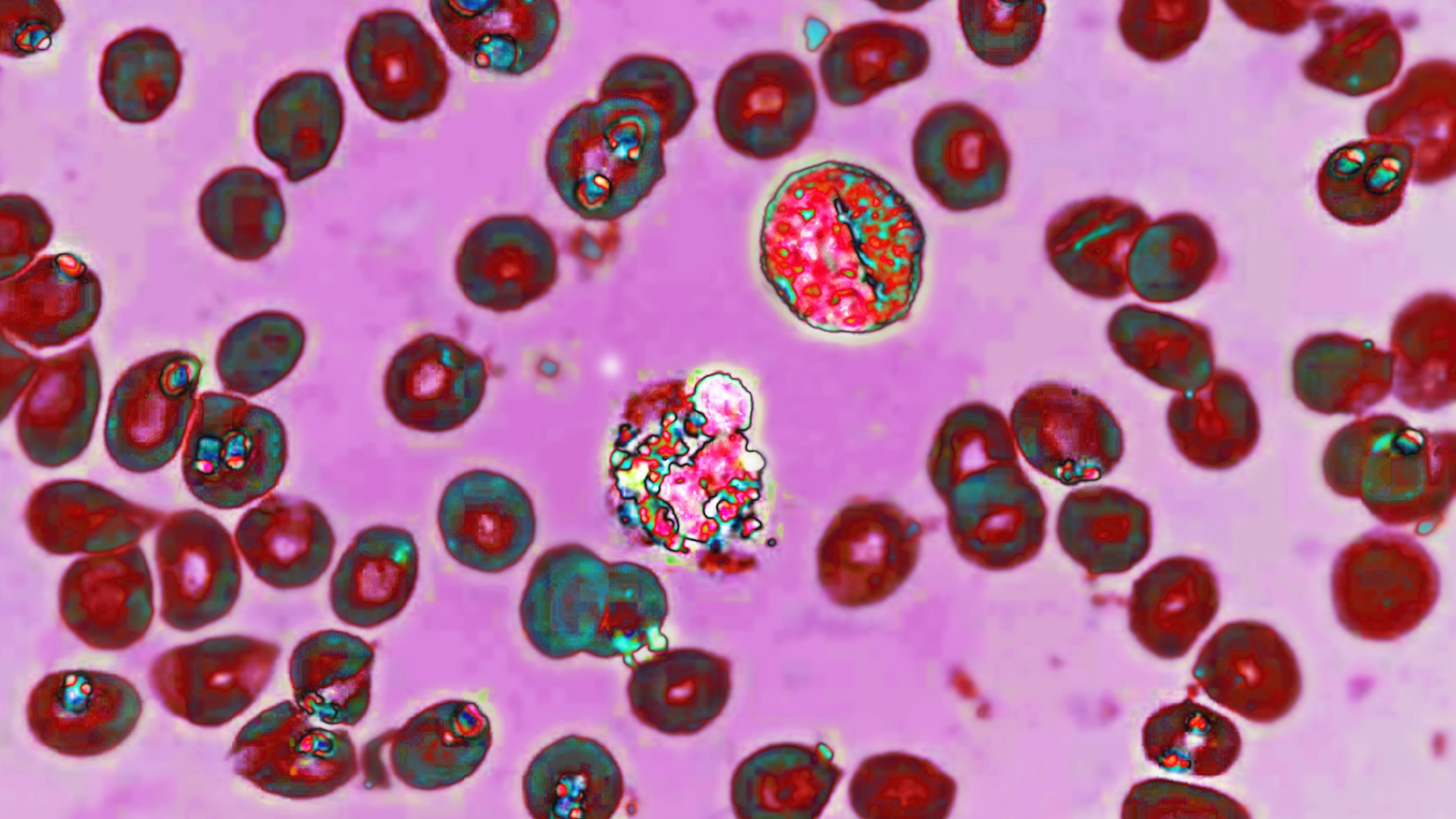

But recent research has also shown that blood-sucking insects — including mosquitoes in the genus Anopheles, which spread the Plasmodium parasites behind malaria — need HPPD to digest their blood meals.

Now, a study published March 26 in the journal Science Translational Medicine provides early evidence to suggest that treating human blood with nitisinone makes the blood lethal to Anopheles mosquitoes. By messing with the HPPD enzyme, the drug effectively makes it so mosquitoes can't detoxify an amino acid found in blood, called tyrosine, so they die after eating.

Related: DNA from dozens of human skeletons unravels history of malaria

With further research, nitisinone could potentially be repurposed as a new malaria-control method, the scientists behind the research hope. Devising additional control methods could be especially helpful given that mosquitoes are becoming ever more resistant to the traditional insecticides used to kill them.

That said, nitisinone is not a "silver bullet," said study co-author Alvaro Acosta-Serrano, a professor of molecular parasitology and vector biology at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. The drug will not prevent people from getting infected with malaria, nor cure people who are already infected, he told Live Science. But nitisinone could reduce the transmission of the disease by shrinking the population of mosquitoes that carry Plasmodium parasites, he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new study, the researchers ran several lab experiments to determine the minimum concentration of nitisinone that would be needed to kill Anopheles mosquitoes. Using the lowest dose possible can help reduce the risk of potential side effects in people taking the drug, as well as decrease the likelihood that mosquitoes would become resistant to it over time, Acosta-Serrano said.

The researchers found that when Anopheles mosquitoes were fed human blood samples containing nitisinone, the insects died. This was true regardless of whether the mosquitoes were resistant to traditional insecticides.

In another experiment, the researchers modeled how nitisinone stacked up against ivermectin, a common drug used to treat various parasitic diseases in humans, including malaria; it's intended to kill parasites in the body but not to kill mosquitoes that bite people. The team found that nitisinone was more effective than ivermectin at killing mosquitoes.

A single dose of nitisinone (approximately 0.1 milligram per kilogram of body weight) could make someone's blood deadly to mosquitoes for around five days, they found. However, no mosquito mortality was observed for "any single dose of ivermectin," the team reported.

In a separate analysis, the researchers fed mosquitoes blood samples from three patients with alkaptonuria who regularly took 2 mg of nitisinone a day. All of the mosquitoes died within 12 hours of feeding. Blood from a patient with alkaptonuria who had not started the treatment was not toxic to mosquitoes.

Taken together, these findings suggest that nitisinone therapy could be a promising new malaria-control method. However, the researchers cautioned that there are still many hurdles to overcome before the drug could be used for this purpose.

For example, the safety of nitisinone still needs to be tested in healthy individuals in the general population, particularly those who live in areas of the world where malaria is common. If the drug were to be used for malaria control, it would be taken by people who otherwise have no need for the treatment, so it would have to have very minimal or no side effects to be worth it.

Scientists will also have to test how nitisinone interacts with common antimalarial drugs, which would still be needed to treat patients with malaria.

Finally, the exact reasons why blocking the tyrosine detoxification pathway is lethal to blood-feeding insects are still unknown, Acosta-Serrano said. Understanding nitisinone's mechanism of action would help scientists predict how easily mosquitoes could become resistant to the drug, he added.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.