Fatal familial insomnia: A genetic condition where people never sleep again

As fatal familial insomnia progresses, patients completely stop sleeping and enter a coma-like state that results in death within months.

Disease name: Fatal familial insomnia (FFI)

Affected populations: The disease affects an estimated 1 to 2 people per million every year, according to the National Organization of Rare Disorders. FFI is passed from parent to child, and between 50 and 70 families worldwide are believed to carry the genetic mutation that causes FFI. Males and females are equally likely to develop the condition.

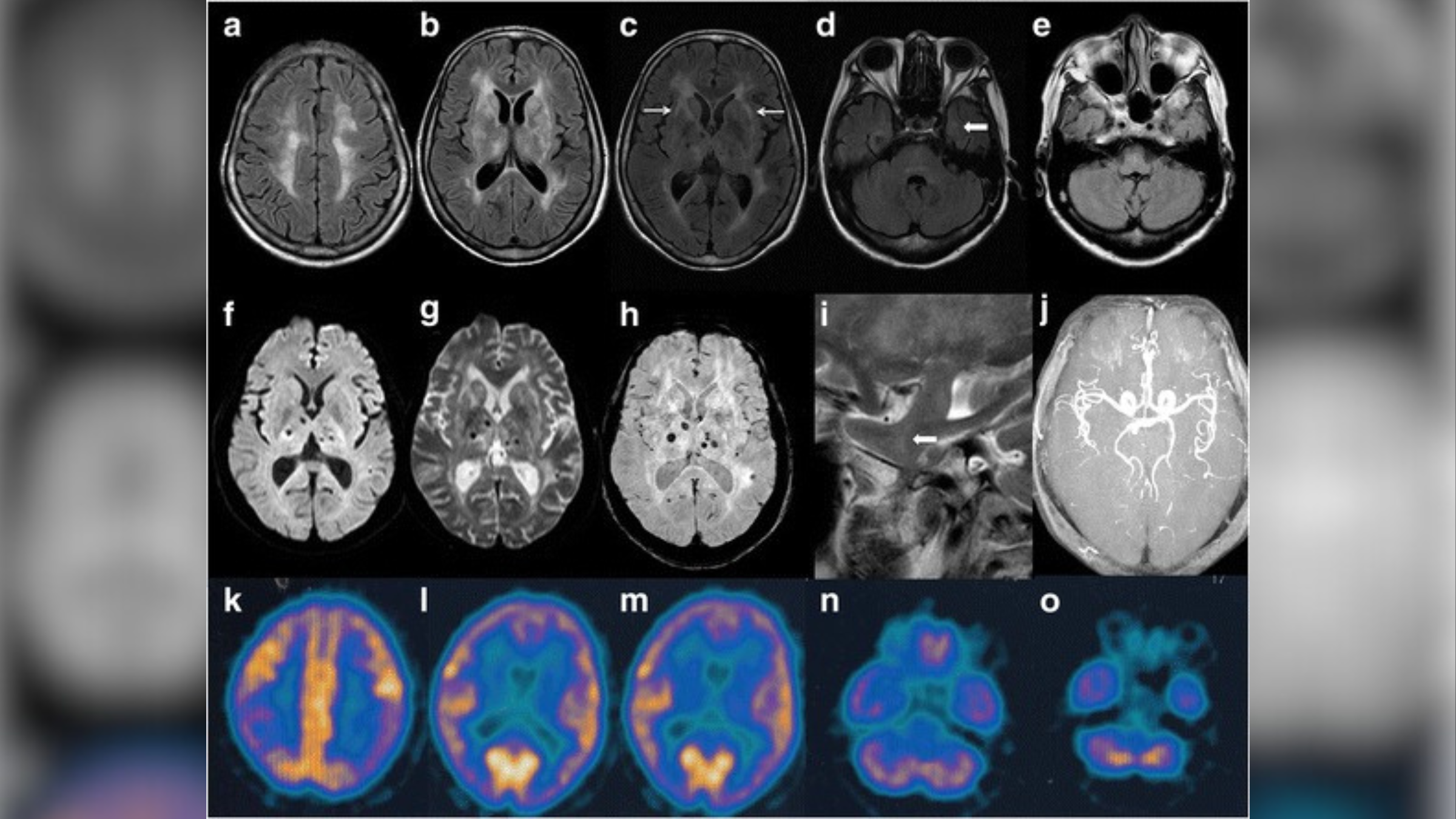

Causes: FFI is a neurodegenerative prion disease that is caused by a mutation in a gene called PRNP, which produces a so-called prion protein. Prions are misfolded versions of normal proteins, and their abnormal shape is toxic to cells in the body, particularly neurons in the brain. One of the tissues that is primarily damaged in patients with FFI is the thalamus, a region of the brain that regulates an array of body functions including sleep, body temperature and appetite.

Children need to inherit only one copy of the mutant PRNP gene from a parent to develop the condition. In rare instances, patients may spontaneously develop mutations in the PRNP gene, despite having no family history of FFI. They can then pass this mutation on to their children in the regular way.

Related: Not all insomnia is the same — in fact, there may be 5 types

Symptoms: The hallmark symptom of FFI is insomnia, or the inability to fall or stay asleep, which progressively worsens over time to the point where patients cannot sleep at all.

Patients with FFI also commonly experience memory loss, high blood pressure, hallucinations and involuntary jerking of their muscles. They may sweat profusely and lose their coordination.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Symptoms usually begin around age 40, but can develop as early as age 20 or as late as age 70. Patients eventually enter a coma-like state and typically die within nine to 30 months after their symptoms emerge.

Treatments: There is currently no cure for FFI. As the disease is so rare, there is also no standard way of treating it. Instead, patients may be given advice on how to best manage their symptoms and live as comfortable a life as possible. For instance, taking the drug clonazepam can reduce muscle jerking.

A medical case report from 2006 showed that trying to induce sleep — for instance, by engaging in rigorous exercise and taking narcoleptic drugs — extended and enhanced the life of 52-year-old man with FFI by about a year, but did not prevent his death.

In 2015, a clinical trial of a drug that aims to prevent the onset of FFI was launched. Over 10 years, 10 people who carry the FFI mutation will be given the antibiotic doxycycline and their prognosis and survival after disease onset will be compared to patients who previously died of FFI. Doxycycline has also been shown to prevent the formation of misfolded proteins in another prion disease, called Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, helping patients live twice as long as those who didn't receive the treatment.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)