Florida man gets 'flesh-eating' bacterial infection after a relative bit him

A resident of Riverview, Florida was bitten by a relative and later developed a "flesh-eating" infection — likely from the bite.

A man in Florida developed a rampant "flesh-eating" infection that tore through his thigh just days after a relative bit his leg during a fight at a family gathering.

The 52-year-old Riverview resident, Donnie Adams, initially noticed a small bump on his left thigh, which emerged two days after he'd broken up a fight between two family members at a gathering, The Tampa Bay Times reported. Thinking the wound looked like a bite mark, Adams went to a local emergency room to get a tetanus shot and antibiotic treatment.

But three days later, "my leg was very sore. I couldn't walk, it was very warm and very painful," Adams told local news network WFLA.

Adams returned to the emergency room at HCA Florida Northside Hospital in St. Petersburg, where doctors determined he needed immediate surgery. Dr. Fritz Brink, general surgeon and wound care specialist, treated Adams and later told the Tampa Bay Times that grey fluid seeped out of Adam's leg as soon as his surgical instruments pierced the tissue. This is a sign of necrotizing fasciitis — colloquially known as a "flesh-eating" infection.

Related: Does the giant blob of seaweed headed to Florida really contain 'flesh-eating' bacteria?

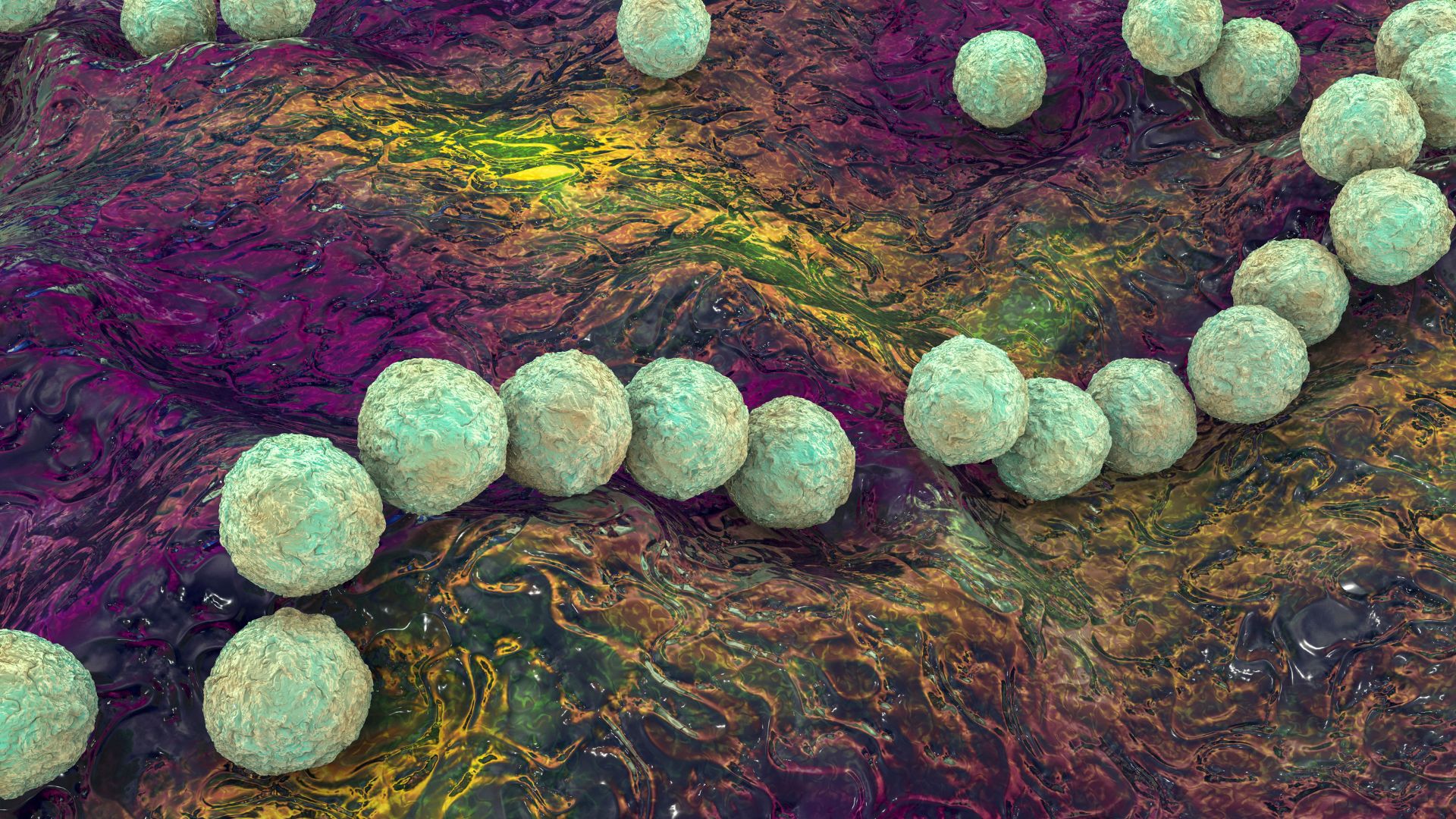

Multiple types of bacteria can cause necrotizing fasciitis, which triggers intense inflammation that causes the infected tissue to rapidly die, or "necrotize." Bacteria known as group A Streptococcus, or group A strep, are likely the most common cause of the gruesome disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, certain microbes found in warm water, including Vibrio vulnificus, are the bacterial species that tend to make headlines.

Flesh-eating bacteria typically enter the body through breaks in the skin, such as cuts, burns, insect bites, or as in Adams' unusual case, human bites. If left untreated, the infections can lead to a life-threatening immune reaction called sepsis, organ failure and death. "Even with treatment, up to 1 in 5 people with necrotizing fasciitis [caused by group A strep] died from the infection" in the past five years, the CDC website notes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To treat necrotizing fasciitis, doctors give antibiotics to kill the bacteria and surgically remove a patient's dead and infected flesh. Adams had about 70% of the tissue removed from the front of his thigh and required a second surgery to remove some infected flesh that had been missed, the Tampa Bay Times reported. He spent three weeks recovering in the hospital and required six months of additional care after discharge, to make sure his thigh wound properly healed.

The hospital doctors told the Tampa Bay Times that they'd never before treated a case of necrotizing fasciitis caused by a human bite. It's unknown whether the culprit bacteria came from the bite itself or entered Adams' skin after the fact, but it's certainly possible that the microbes came from the biting relative's mouth, Brink told the Times.

"Normal bacteria in an abnormal spot can be a real problem," Brink said. (The news reports don't note what specific species of bacteria infected Adams.)

Adams' leg is now heavily scarred and occasionally painful, but it's healed and fully functional. Regarding the fight that started it all: "The parties involved are very sorrowful," he told the Times.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Measles has long-term health consequences for kids. Vaccines can prevent all of them.

100% fatal brain disease strikes 3 people in Oregon