In world 1st, virus spotted attached to 2nd virus

The interaction was captured using a specialized piece of kit called a transmission electron microscope.

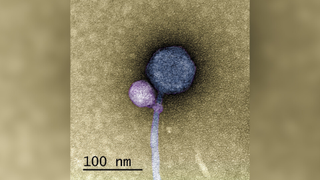

In a world first, scientists have observed one virus latching onto another.

The interaction was captured in astonishing detail using a microscope that fires beams of electrons at its subject. The finding revealed how these two different viruses, both categorized as "bacteriophages," interact and may have co-evolved.

"No one has ever seen a bacteriophage — or any other virus — attach to another virus," lead study author Tagide deCarvalho, an assistant director of the College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences Core Facilities at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, said in a statement.

The two pictured viruses both infect bacteria and are known as bacteriophages, or simply phages. But the smaller one, shown in purple, is a satellite virus, meaning a virus that is incapable of infecting and replicating inside host cells without the assistance of a "helper" virus — here shown in blue.

Related: Mammal cells use some viruses like vitamins, study hints

Satellite viruses rely on helper viruses to replicate their DNA once they infiltrate a cell. To coordinate this, the satellite and helper sometimes need to infect the same cell simultaneously, so they need to be close to each other when this happens. However, the new image captures what is believed to be the first observation of a satellite actually attaching itself to a helper. It is attached at the virus' "neck" — where the helper's outer shell connects to its tail.

The never-before-seen interaction was described in a study published Oct. 31 in the Journal of the International Society for Microbial Ecology.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers made the serendipitous discovery while looking at environmental samples containing a family of bacteriophage satellites that infect Streptomyces bacteria. At first, they thought the samples had been contaminated as they contained large sequences of DNA — the expected bacteriophages — and smaller, unrecognizable sequences that didn't match anything they knew.

Upon further inspection under the microscope, the authors discovered that the samples contained what looked like helper and satellite bacteriophages. About 80% of the helper phages had a satellite bound to their neck. In some of the remaining helpers, the authors observed what looked like "bite marks" — the aftermath of an interaction. These "bites" were actually remnant tendrils from a satellite.

The authors analyzed the genomes of these bacteriophages as well as their bacterial hosts and discovered that the satellites had genes that coded for their outer protein shell but not the key genes needed to replicate within bacterial cells. This further supported the idea that these two types of bacteriophages were interacting with each other.

But why would the satellite grab hold of its helper's neck? It turns out that some satellites lack a gene needed for them to integrate into the genome of bacterial host cells after entering them. Most satellite viruses can hide out in the host's DNA, so when the right helper comes along, the satellite can then replicate. But without that key gene, a satellite would need its helper to chauffeur it into the host's DNA, so it can survive.

To guarantee that the satellite-helper pair enters the host cell together, the satellite attaches to the helper using a unique adaptation to its tail, the researchers found.

"These findings demonstrate an ever-increasing array of satellite strategies for genetic dependence on their helpers in the evolutionary arms race between satellite and helper phages," the authors wrote in the study.

The researchers say the discovery could raise questions about how these bacteriophages evolved, including how satellites came to attach to their helpers and how often this happens.

"It's possible that a lot of the bacteriophages that people thought were contaminated were actually these satellite-helper systems," deCarvalho said in the statement. "So now, with this paper, people might be able to recognize more of these systems."

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)