Measles has long-term health consequences for kids. Vaccines can prevent all of them.

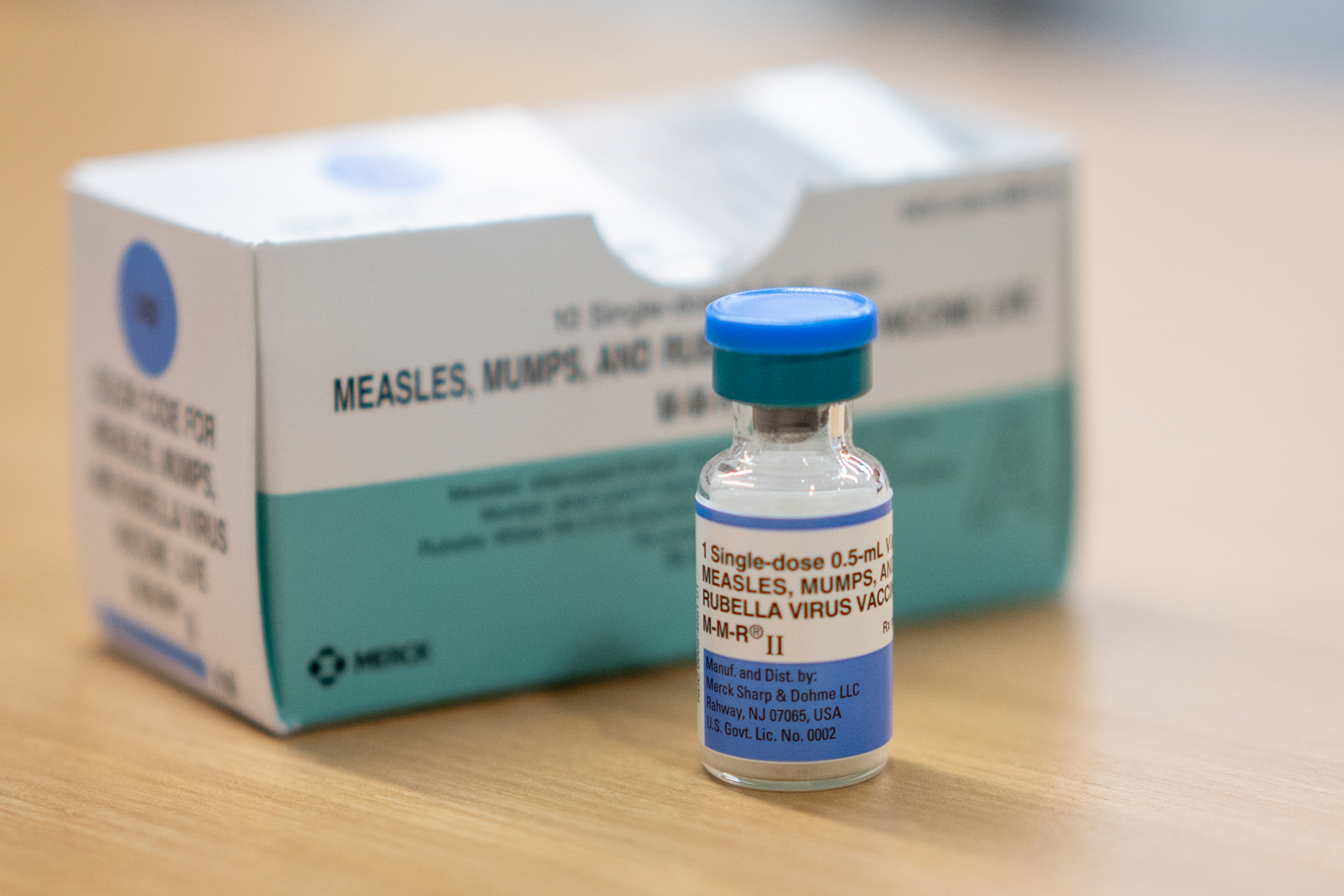

Measles can erase the immune system's "memory" and cause a rare but fatal health condition. The MMR vaccine prevents these repercussions, evidence shows.

Measles kills between 1 and 3 out of every 1,000 children infected with the viral disease. But even for those who survive the illness, the long-term consequences of measles can be serious. Long after a person recovers from their acute infection, their immune system is compromised — and in rare cases, the measles virus can hide out in the nervous system, roaring back to cause a fatal disease years later.

In the short term, measles, caused by a highly contagious virus, usually causes fever, respiratory symptoms like coughing, and a distinctive rash that spreads from the hairline down the body. It appears as if a "bucket of rash" is poured over the head, according to Patsy Stinchfield, an infectious disease nurse practitioner and the most recent past president of the non-profit National Foundation for Infectious Diseases (NFID).

Because the two-shot measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine is 97% effective at preventing measles, many U.S.-based medical professionals have never seen the disease that's now causing a major outbreak in Texas and bordering states, experts told Live Science. Cases have been so low in the U.S. that measles was declared eliminated from the country in 2000.

However, Stinchfield responded to a 2017 measles outbreak in Minnesota and saw multiple kids affected.

"The kids that come into the emergency room and get to go home, even those kids look like rag dolls over their parents' shoulders," Stinchfield told Live Science. "They're miserable."

An estimated 1 out of every 5 kids who catch measles will be hospitalized, and 1 in 20 will get pneumonia, which is what kills most children who die of the disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Some of these hospitalized children will need to be put on a ventilator to recover, Stinchfield said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In about 1 in 1,000 cases, measles causes brain swelling, or encephalitis, which can cause seizures. When it's not fatal, the swelling itself can subside, but it can cause permanent brain damage and other lasting side effects, such as blindness or deafness.

"Immune amnesia"

Even patients with milder cases of measles can suffer long-term knock-on effects.

Measles binds to a receptor that happens to be present on several important immune cells: T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and long-lived plasma cells. These are cells that "remember" past infections for decades, thus enabling the immune system to rapidly mount a defense if it encounters a pathogen again.

It does this by making protective proteins called antibodies, along with summoning other immune defenders. But a 2019 study found that, after a measles infection, people lose between 11% and 73% of the antibodies they had to previous infections.

To recover from this so-called immune amnesia, a person would have to catch all those diseases again, said Stephen Elledge, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School and the senior author of that 2019 research. In the meantime, that means they're vulnerable to a whole host of infections after contracting measles.

Furthermore, a 2015 study led by Elledge's collaborator, epidemiologist Dr. Michael Mina, found that kids who got measles had a higher death rate from other infectious diseases in subsequent years.

These infectious diseases, including measles, are the primary reason that nearly 1 in 5 children died before their fifth birthday in the U.S. back in 1900. A 2024 study published in The Lancet estimated that vaccination has saved at least 154 million lives since 1974, alone.

"The vaccine is much more important than we thought it was," Elledge told Live Science. "It doesn't just save from the 0.1% or 0.2% of children that die [of measles]. It may be the 0.5% to 1% of the kids that get measles [and] might succumb to another infection. That starts to get a little bit bigger."

A lingering threat

The measles virus is capable of replicating in the brain, said Ross Kedl, a professor of immunology at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. In some cases, the immune system beats the virus back and the person seems to recover, but measles still lurks in their nervous system.

The nightmarish effect of this long-term persistence is a condition called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). This is a progressive neurological disorder that might start with mood changes and muscle tremors; then, as it progresses, the person starts losing speech, vision and hearing. After about two years, the person falls into a coma and dies.

"The person you knew transforms in front of you and wastes away and then they're gone," Kedl told Live Science.

The risk of SSPE is highest in kids who catch measles before the age of 2, at about 1 in 1,000, Kedl said. For older patients, the risk is closer to 1 in 10,000, which is still twenty times higher than the risk of serious side effects from any vaccine on the market, he said. (1 in 10,000 is 20 in a million, whereas serious adverse events from vaccines occur at a rate of roughly 1 to 2 per million, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.)

Because SSPE is most common in kids who catch measles before age 2, and it tends to emerge about seven years after their acute infection, the victims are typically around the age of 9 or 10.

SSPE happens because the measles virus can go dormant within the nervous system, similar to how the chickenpox virus — called varicella — can go dormant and cause shingles decades later. One benefit of the varicella vaccine is helping prevent the chickenpox infections that can lead to shingles down the line; similarly, the MMR vaccine prevents SSPE.

Measles vaccines save lives and prevent disability

The MMR vaccination has effectively cratered the annual number of U.S. measles cases — which totalled 3 million to 4 million before vaccines were introduced, according to the CDC. Because of the vaccine's success, people forget how bad the disease can be, said Dr. Michelle Barron, senior medical director of infection prevention and control at UCHealth, a medical system in Colorado.

With vaccination rates sliding in various jurisdictions, there are now active measles outbreaks in Texas, New Mexico, Kansas and Ohio, with scattered cases in 16 other states, Barron told Live Science. There are also outbreaks in Mexico and Canada. It's important to be vaccinated to protect both yourself and those who can't be vaccinated, including babies under 1 year old, she said.

There are no treatments for measles that can reduce the risk of the disease's knock-on complications, Barron said. The "natural" remedies that have been pushed by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and others, such as vitamin A, are not measles treatments. Rather, they are treatments for malnutrition that are often used to help support kids with measles in places with extreme poverty and childhood malnourishment, Barron said.

What does cut the risk of knock-on effects of measles? Not catching the disease in the first place.

"Vaccine is protective against all of these complications," Barron said.

Editor's note: This article was originally published on April 3, 2025.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Parasitic worm raises risk of cervical cancer, study finds

Cancer: Facts about the diseases that cause out-of-control cell growth