Malfunctioning mitochondria may drive Crohn's disease, early study hints

A new study in mice suggests that dysfunctional mitochondria may change the gut microbiome and thus drive Crohn's disease.

Defective mitochondria may disrupt the gut microbiome, driving the development of Crohn's disease, new research in mice suggests.

If these findings hold true in humans, they could ultimately lead to the development of targeted treatments that get at the root cause of the condition.

Crohn's disease is a chronic inflammatory disorder that affects the gastrointestinal tract, causing symptoms such as lower abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea and fever. The exact cause of the condition is unknown, but it's thought to stem from dysfunction in the immune system and, potentially, genetic factors. Treatments mainly include immunosuppressants and anti-inflammatory medications, which target the general inflammatory symptoms of the disease.

Research in patients suggests that Crohn's may be partly caused by changes in the composition and function of the gut microbiome, the collection of microbes that live inside the digestive tract. Those microbes can influence inflammatory cells of the immune system, so when they change, the immune system changes in turn.

Related: Scientists invent tool to see how 'healthy' your gut microbiome is — does it work?

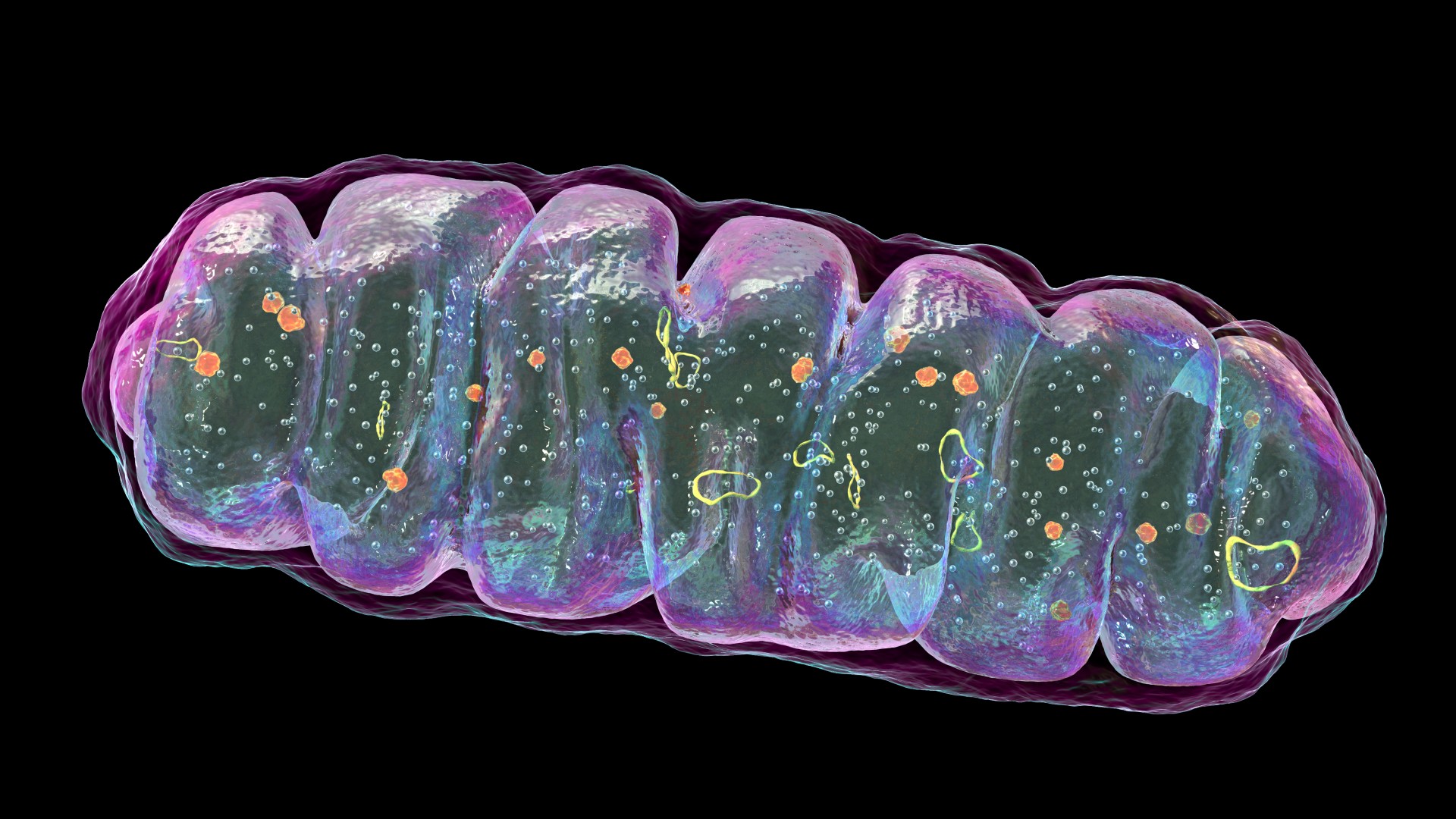

Now, a study published Aug. 14 in the journal Cell Host & Microbe may explain why these microbial changes occur. It turns out that disruptions to mitochondria — the "powerhouses" of cells — in the intestine can cause tissue damage that then alters the composition of the gut microbiome.

The study authors made this discovery after breeding genetically modified mice that couldn't produce a key mitochondrial protein known as HSP60. Cells that line the inside of the intestine specifically lacked this protein. The team focused on mitochondria because earlier research had flagged that these powerhouses may be tied to Crohn's disease.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the team took tissue samples from the intestines of the mice and analyzed them under the microscope, they found signs of inflammation and tissue injury that resembled Crohn's disease in humans. For instance, they saw a decline in the amount of mucus made by the intestinal tissue, which would normally protect the organ's inner lining.

In separate experiments, the team bred mice that lacked both HSP60 and gut bacteria. Notably, these mice didn't develop any tissue damage in their intestines. That suggests that the inflammatory process associated with Crohn's may be mediated by intestinal microbes, because when they're missing, that damage disappears.

To narrow down which bacteria might be the culprits, the team ran a DNA analysis using tissue samples from mice with intact microbiomes but dysfunctional mitochondria. This experiment suggested that a common group of gut bacteria known as Bacteroides begins to dominate the intestines following mitochondrial-induced tissue damage.

Bacteroides normally live in the guts of mammals, including humans, without causing a stir. However, they can become opportunistic pathogens, meaning that they may seize the opportunity to cause infections if, for instance, the intestinal wall is compromised.

More research is needed to figure out why these bacteria thrive after tissue injury and how they might contribute to the inflammation seen in Crohn's, the team wrote in their paper. Future work will also be needed to decipher what causes mitochondrial damage to occur in the first place, as well as to see whether the same chain reaction happens in humans.

If so, these findings in mice may someday inspire targeted treatments for Crohn's disease.

Such drugs could act on mitochondria or somehow tweak the interactions between the mitochondria and gut microbiome, study co-author Dirk Haller, a professor of nutrition and immunology at the Technical University of Munich, said in a statement.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.