Mysterious virus-like 'Obelisks' found in the human gut and mouth

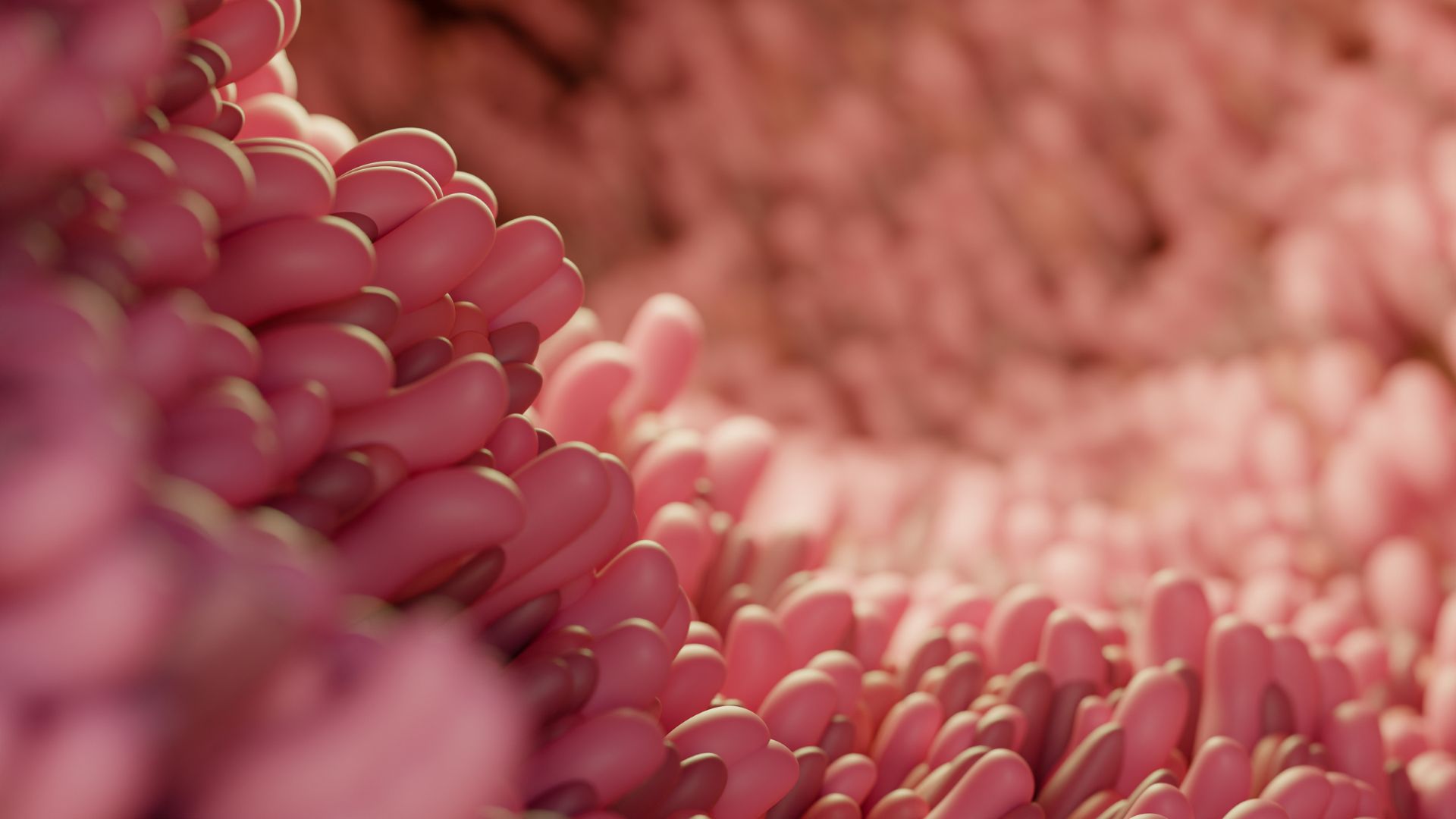

Scientists have uncovered a unique group of virus-like entities in the human gut and mouth.

Scientists have uncovered a never-before-seen class of virus-like entities hiding in the human gut and mouth, and these "viroids" may influence the gene activity within the human microbiome, Science reported.

The researchers confirmed one host for these viroids, namely, a common bacterium found in the mouth called Streptococcus sanguinis. They've yet to confirm additional hosts, but they suspect at least a fraction are bacteria.

Viroids are tiny loops of RNA, a genetic cousin of DNA, and they've been found to infect primarily plants, such as potatoes. Viroids differ from larger, RNA-based viruses in several ways. First, they're naked, lacking the protective shells that viruses use to hold their genetic material. Second, their RNA doesn't contain instructions to build proteins; whereas viruses carry instructions for their outer shells and for certain enzymes they need to replicate, viroids co-opt these enzymes from their hosts.

Although viroids were once thought to infect only plants, recent studies suggest they may infect additional hosts, such as animals, fungi or bacteria. In the new study, researchers searched for possible viroids among the genes of microbes that reside in the human body.

Related: 70,000 never-before-seen viruses found in the human gut

In a report published Jan. 21 to the preprint database bioRxiv, the team introduced "Obelisks," a newly named class of viroid they discovered in the human gut and mouth. In all, they identified nearly 29,960 examples of the viroids. (The work has not yet been peer-reviewed or published in a scientific journal.)

They named them Obelisks because the viroids' secondary structure — a 3D shape they assume by folding onto themselves — is predicted to look like a thin rod.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using previously published data, the researchers combed through readouts of gene activity in different microbial communities within the body. These gene-activity summaries are known as "metatranscriptomes."

They found that Obelisks were present in roughly 7% of the metatranscriptomes from human feces. These stool samples give a snapshot of gene activity in the gut microbiome. The team also found the newly named viroids in 17 out of 32, or about 53%, of the mouth metatranscriptomes they screened.

In further analyses, the team was able to match an Obelisk with its host, S. sanguinis. "While we don't know the 'hosts' of other Obelisks, it is reasonable to assume that at least a fraction may be present in bacteria," they wrote in the preprint.

Interestingly, some of the newfound Obelisks seemed to contain instructions for enzymes needed for replication, making them more complex than viroids that had been described previously, Science reported. Like most viroids, though, they still lacked instructions for a protective outer shell.

It's still unknown how or whether these viroids affect human health, although they may shape the human microbiome, since at least some infect bacteria. There's also ongoing discussion of whether viruses evolved from viroids or if viroids actually evolved from viruses, so this new discovery may help fuel that debate.

Read more in Science.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.