New species of bacteria discovered after man is bitten by stray cat

The case highlights that there are unknown illnesses that can pass between cats and humans.

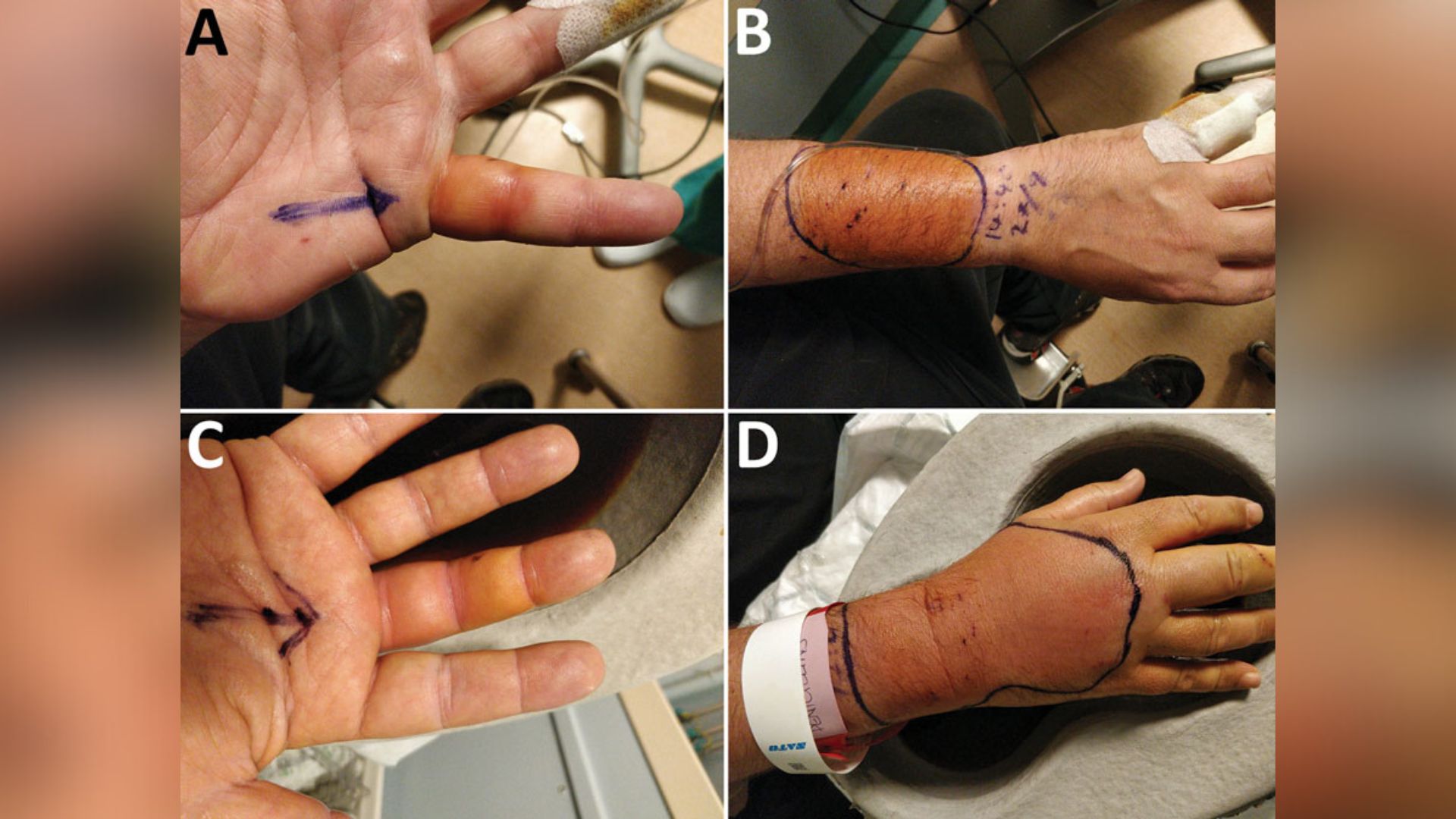

A man developed an "extensive" infection that caused his hands to swell after being bitten by a stray cat that was carrying an unknown species of bacteria, a new case report reveals.

The 48-year-old went to an emergency department in the U.K. because of painful swelling that developed in both his hands eight hours after he'd been bitten multiple times by a stray cat.

After washing and dressing his wounds, doctors gave him antibiotics and a booster dose of the tetanus vaccine to protect against infection by Clostridium tetani bacteria, which can cause painful muscle spasms, seizures and potentially death.

A day later, the patient returned to hospital as the infection had spread deep into the tissue of his left little finger, right middle finger and both his forearms, which had grown red and even-more swollen. He had signs of cellulitis, a bacterial infection in the deep layers of the skin, and tenosynovitis, a condition in which the protective, fluid-filled tissue layer around the tendon becomes inflamed.

Related: A woman needed her hands and legs amputated after contracting infection from dog 'kisses'

Doctors administered several antibiotic drugs into the patient's veins, and they removed damaged tissue from his infection sites and washed out the remaining wounds. After that, the man was given oral antibiotics to take for five days and fully recovered.

Scientists analyzed tissue taken from the patient to find out what caused the infection. At first, scientists struggled to identify bacteria in the sample, probably because of the previous antibiotic treatment. They did, however, notice some Staphylococcus epidermidis that had been growing on the man's right middle finger, and a "Streptococcus-like organism" they couldn't initially identify. The mystery bacterium didn't match any genetic records of known bacterial species, but the team determined that it belonged to the genus Globicatella.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Globicatella bacteria are small microbes that resemble the more commonly known Streptococcus genus, which includes the Group A Streptococcus bacteria that can cause strep throat, scarlet fever and "flesh-eating infections." Until now, scientists only knew two species of Globicatella: G. sanguinis — which can infect humans and cause blood, heart, central nervous system and urinary tract infections — and G. sulfidifaciens, which so far has been found to infect only animals, such as pigs, cows and sheep.

The newly identified microbe's genome bacteria differed from that of G. sanguinis and G. sulfidifaciens by around 20%, which indicated it was "a distinct and previously undescribed species." Importantly, the newfound species responded well to many antibiotics, including some that other Globicatella bacteria have shown resistance to in the past, such as cefotaxime and penicillin.

In the U.S., 1% of emergency department visits are caused by dog or cat bites, with our feline friends being responsible for 15% of these visits. "Cats are major reservoirs of zoonotic infections," the case report authors wrote. "Their long, sharp teeth predispose to deep-tissue bite injuries and direct inoculation of feline saliva gives high risk for secondary infection."

Bites may become infected with bacteria that live in the cat's mouth, such as Pasteurella and Streptococcus species. Cat bites, like those from other domestic animals, can also cause rabies and tetanus infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises that anyone who is bitten or scratched by an animal should immediately clean the wound for at least 20 minutes with soap and running water then seek medical attention.

The authors of the new case report published their findings June 14 in the CDC journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents