Oregon's 1st bubonic plague case in 8 years tied to patient's pet cat

Oregon saw its first human case of bubonic plague in eight years, and officials suspect the infected person's cat sickened them.

A person in Oregon has been diagnosed with bubonic plague — the first case of the illness reported in the state since 2015.

The patient, in Deschutes County, likely caught the infection from their pet cat, which was showing signs of the illness, health officials said in a statement on Feb. 7.

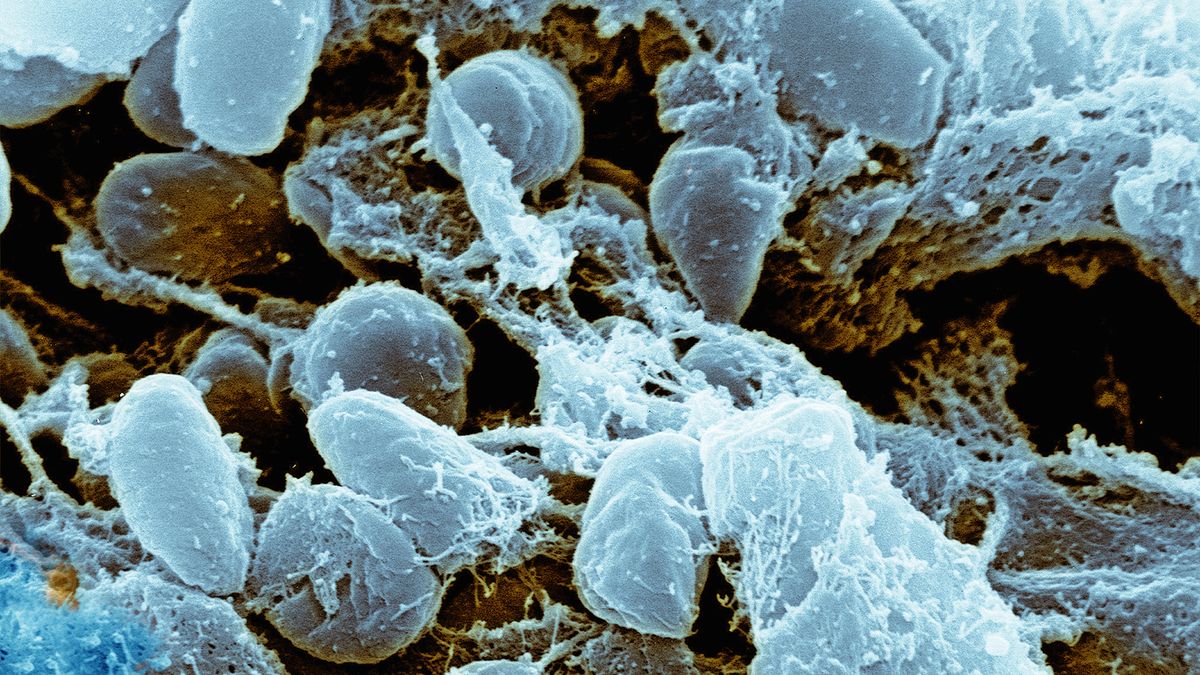

In medical terms, plague commonly refers to an infection caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, and bubonic plague is the most common form of the disease. It's characterized by an infection of the lymphatic system, the body's drainage system, which causes lymph nodes to become inflamed and swell into so-called buboes.

Bubonic plague is most famously associated with the Middle Ages, notably "The Black Death," which is estimated to have killed between 50% to 60% of the population of Europe.

The plague was first introduced into the U.S. in 1900, and although no cities have had plague epidemics since 1925, around seven people are still infected each year, nationwide. These infections happen mainly in northern New Mexico, northern Arizona, southern Colorado, California, western Nevada and southern Oregon — although Oregon hasn't seen a case in years.

Nowadays, the disease can be treated with antibiotics if caught early, but it can quickly become fatal if left untreated.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Y. pestis can be transmitted to humans from infected animals, such as rodents, dogs and cats. People can catch the bug through direct contact with an animal's contaminated fluids or tissues. Most often, though, people develop the infection from the bite of a flea carrying the bacteria.

Human-to-human transmission is rare, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); when it does happen, it usually involves pneumonic plague, which infects the lungs and is transmitted through the air.

In the case of bubonic plague, the bacteria enter the body and spread through the lymphatic system to the nearest lymph node, where they trigger inflammation, resulting in the development of a painful bubo. Patients may also develop symptoms such as fever, headaches and chills.

If left untreated, bubonic plague can spread to the lungs, leading to pneumonic plague, which is always fatal without treatment. By comparison, untreated bubonic plague has a lower fatality rate, around 50%.

In this particular case, the person was likely infected by their cat, the Deschutes County officials said. The animal was "very sick" and had an abscess on its body that was draining, suggesting it had a "fairly substantial" infection, Fawcett told NBC News. In central Oregon, plague is most likely to be carried by squirrels and chipmunks, but mice and other rodents can also carry the bacteria, and cats can then pick it up from the rodents, officials said.

In the recent case, healthcare professionals rapidly identified the illness and treated it in its early stages, so there is little remaining risk to the community. No further cases have been identified in the region, the officials said.

"All close contacts of the resident and their pet have been contacted and provided medication to prevent illness," Dr. Richard Fawcett, the county health officer, said in the statement.

The county officials emphasized that plague is still rare in Oregon. The illness was previously last diagnosed in Oregon in 2015, after a 16-year-old girl from Crook County was bitten by a flea during a hunting trip.

The officials provided several tips to prevent the spread of plague, including avoiding contact with rodents and fleas at all times; keeping pets on a leash when outdoors and protecting them with flea-control products; and keeping wild rodents out of the home.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)