Situs inversus: The condition where your organs are on the 'wrong' side

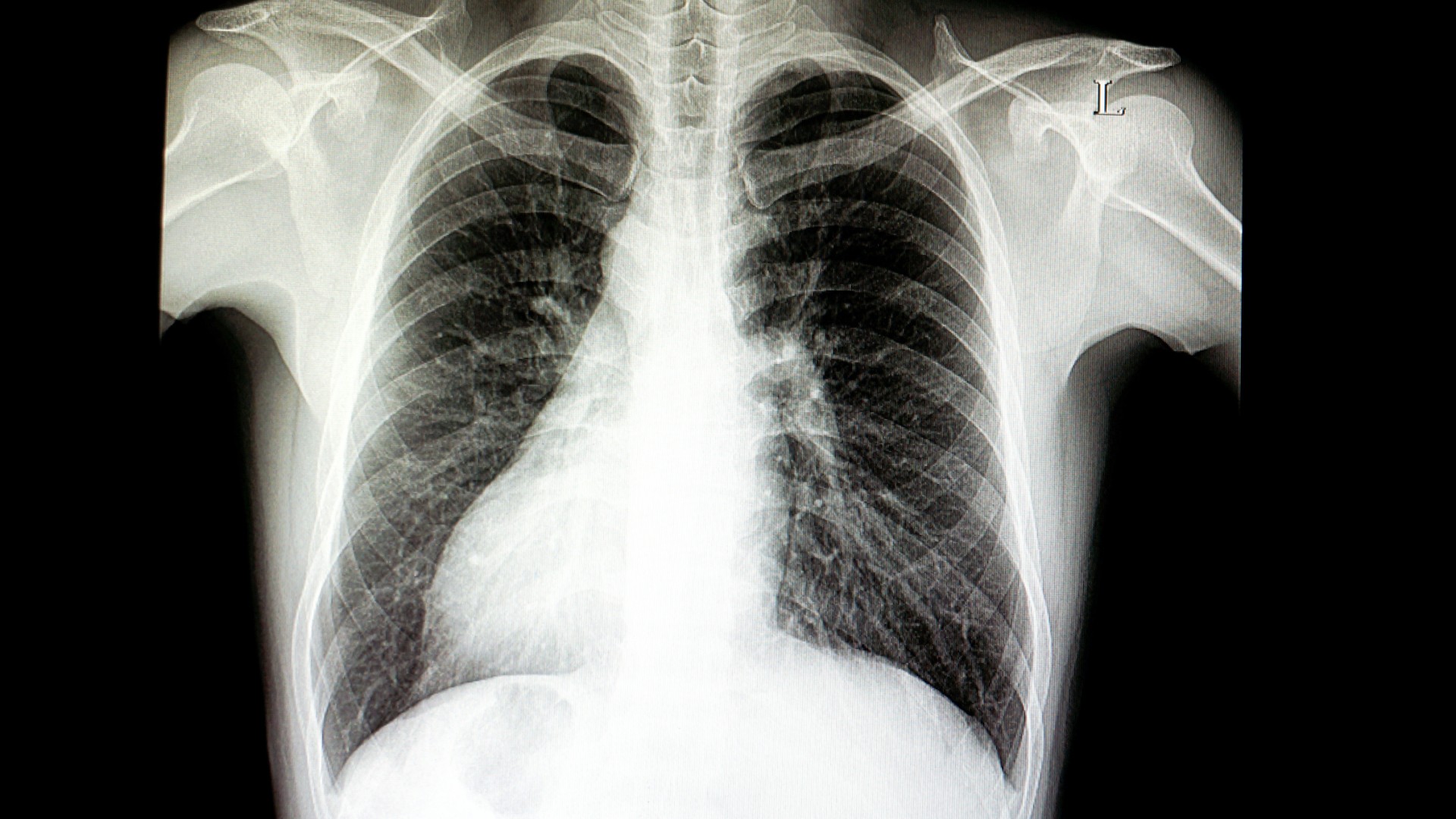

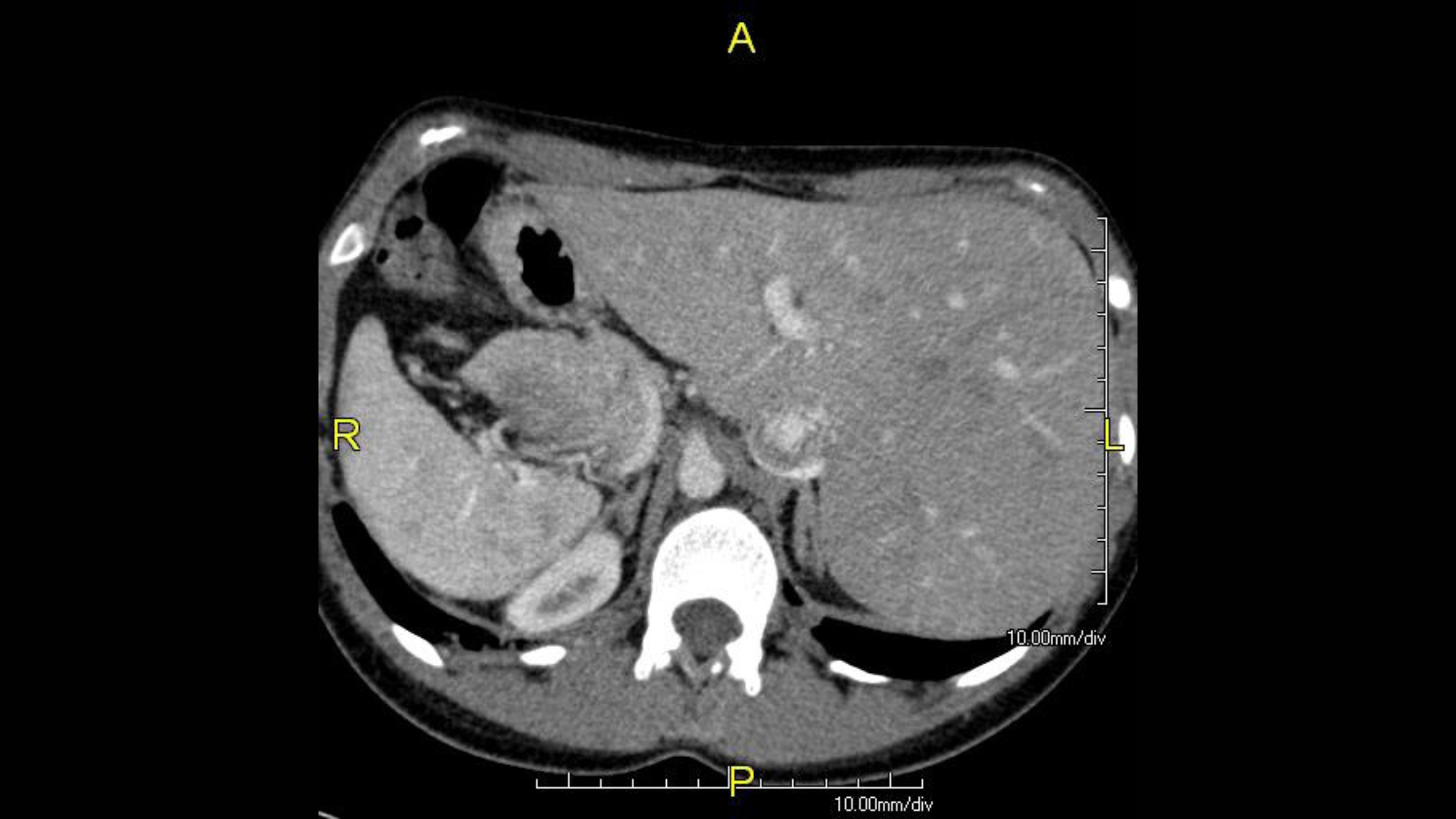

Situs inversus is a rare genetic condition that causes the organs in the chest and abdomen to be located on the opposite side from where they're usually found, like a mirror image.

Disease name: Situs inversus

Affected populations: Approximately 1 in 10,000 people have situs inversus. Men are 1.5 times more likely than women to experience the condition.

Causes: Situs inversus is a genetic condition that causes organs in the chest and abdomen, such as the liver and spleen, to be flipped across the midline of the body. If the heart's position is also flipped — a phenomenon known as dextrocardia — then the condition is described as situs inversus totalis.

Situs inversus is caused by mutations in one or more genes. More than 100 genes have been tied to defects in the "sidedness" of the body, such as the gene NME7, which encodes a protein that helps regulate the creation of tube-like cellular structures, called microtubules. These structures have numerous functions, including supporting cell shape and their ability to move around the body.

Related: 10 body parts that are useless in humans (or maybe not)

Situs inversus is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, meaning that both parents need to pass on a mutated gene for their children to develop it.

People may have situs inversus on its own, or alongside another condition such as primary ciliary dyskinesia. This is when there's dysfunction in cilia — the tiny, wiggling hair-like structures that keep the airways, ears and sinuses free from infectious germs. During embryonic development, cilia help determine the left-right axis of the body.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Symptoms: Many people with situs inversus will not develop any notable symptoms from the condition — although the positions of their organs are flipped, the organs still work normally. Many individuals may not even realize that they have situs inversus until they are examined by doctors for another, unrelated condition.

However, between 5% and 10% of people with situs inversus have heart defects that are present from birth. And those who also have primary ciliary dyskinesia may be more likely to develop respiratory infections, such as bronchitis and sinusitis, in which the airways and the sinuses are inflamed, respectively.

If they are unaware of their condition, people with situs inversus may also be at risk of diagnostic errors if they're hospitalized for certain ailments. For instance, appendicitis typically causes pain on the lower right-hand side of the abdomen, where the appendix is normally located. But this condition may be missed or diagnosed later than usual if the pain a person experiences is on their left-hand-side instead.

Treatments: As situs inversus doesn't usually cause any symptoms, there is generally no need for treatment. Instead, treatment is focused on targeting the symptoms of any co-occurring conditions, should any emerge.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)