The deadly 'black fungus' infection that decimates flesh

Mucormycosis is a rare fungal infection. Most people are exposed to the fungi behind the disease regularly, but in certain individuals, the microbes can end up being deadly.

Disease name: Mucormycosis, also known as "black fungus"

Affected populations: Mucormycosis is a potentially fatal fungal infection that typically affects people with weakened immune systems, such as those with diabetes or severe COVID-19, including people in recovery from the infection. It can also affect individuals who have received a solid organ transplant or who have a low number of white blood cells, a type of immune cell that normally fights infections. People with HIV and those who use immunomodulating drugs are also at high risk of developing mucormycosis.

The World Health Organization estimates that cases of mucormycosis range between 0.005 and 1.7 per million people worldwide. The burden of the disease is much higher in specific countries, such as India, where there are approximately 80 times more cases at any point in time, potentially influenced by climatic factors and the dominance of certain fungal species in the environment.

The exact incidence of mucormycosis in the United States is unknown; because the condition is rare, there is no national surveillance program to track the disease. However, a study in San Francisco in the late 1990s estimated that there may be 1.7 new cases of mucormycosis per million people every year.

Related: 'Black fungus' treatment runs short in India as new cases of infection emerge

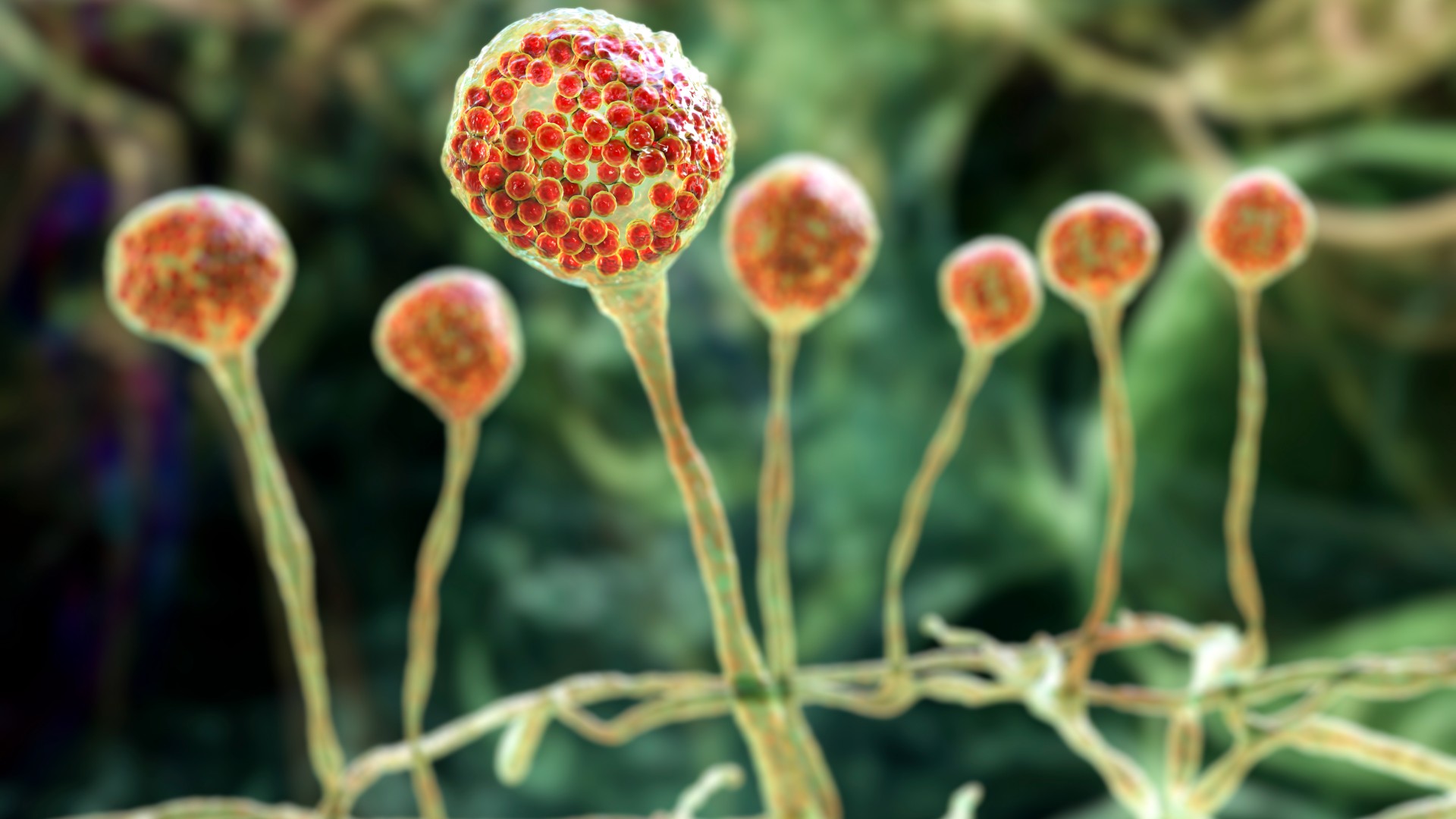

Causes: Mucormycosis is caused by a group of fungi known as mucormycetes — in particular, species in the genus Rhizopus. Mucormycete spores are found naturally in the environment, including in soil, fallen leaves, compost, animal dung and the air. People can get mucormycosis after inhaling or ingesting these spores or if the spores accidentally enter the body via a cut or burn.

Mucormycete spores live harmlessly in many people's bodies, and they typically cause infection only in some individuals who have weakened immune systems. Most cases of mucormycosis occur randomly — in other words, they're not linked to a common infection source. However, outbreaks of the disease have been reported; for instance, health care settings can see outbreaks if fungal spores contaminate hospital supplies or ventilation systems.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Once inside the body of a vulnerable person, mucormycete fungi invade the blood vessels, causing blood clots to form and tissues to become deprived of nutrients and oxygen and die.

Symptoms: Symptoms of mucormycosis differ depending on the part of the body that is affected. These body parts can include the sinuses, lungs, skin, stomach and intestines.

Most mucormycosis infections tend to occur in the sinuses or the lungs after a person inhales fungal spores from the air, which then triggers symptoms such as facial swelling, headaches, fever, cough and chest pain. Mucormycosis infection can also spread from the respiratory system to other parts of the body, such as the brain, spleen and heart.

Overall, death rates for mucormycosis usually exceed 50%, even with medical care.

Mucormycosis is not contagious — people can pick up the spores from the environment, but they cannot then spread those spores to others. In other words, the disease cannot be transmitted from one person to another.

Treatments: It is crucial to diagnose mucormycosis and begin treatment as early as possible. This treatment involves taking antifungal drugs — usually amphotericin B — to kill the fungi that cause the infection, as well as surgically removing any dead tissue to help prevent spores from spreading to other regions of the body.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.