Tularemia: The 'rabbit fever' that can fatally infect humans

Tularemia, or "rabbit fever," is an infectious disease that normally affects animals but can spread to humans, sometimes via tick and deer fly bites.

Disease name: Tularemia, also known as "rabbit fever" or "deer fly fever"

Affected populations: This disease is rare in the U.S. Between 2011 and 2022, 2,462 cases of tularemia were reported in 47 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Historically, human tularemia infections have been reported in every U.S. state except Hawaii. They are especially likely to occur in rural areas of Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma and Kansas, and they usually happen between May and September. Most cases occur in children, especially males.

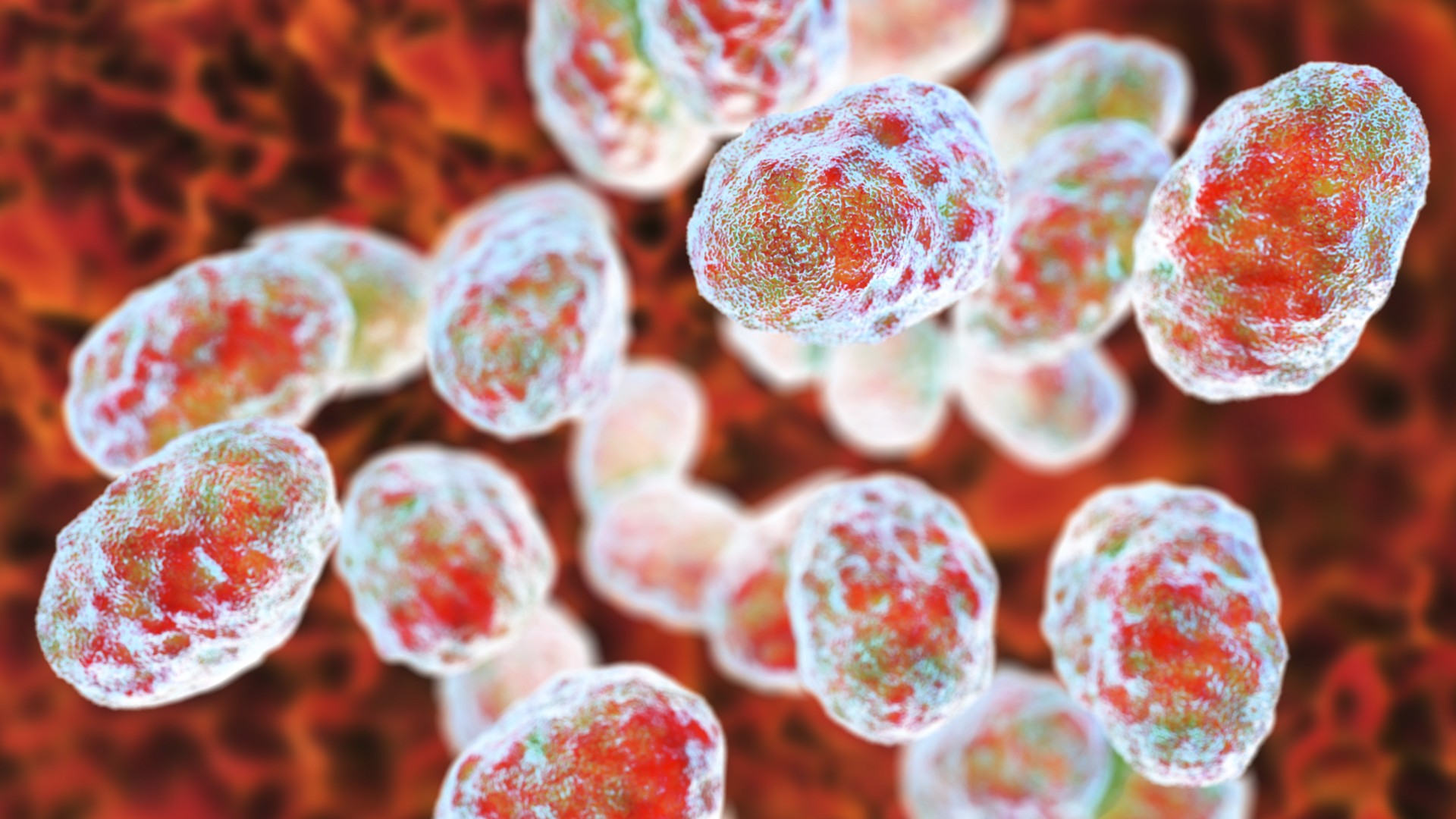

Causes: Tularemia is an extremely infectious disease caused by Francisella tularensis bacteria. The microbe is found throughout the Northern Hemisphere and occasionally in the tropics and Southern Hemisphere.

Related: 'Unusual' beaver die-off in Utah caused by 'rabbit fever,' which can also infect humans

There are four types, or subspecies, of F. tularensis, which differ in terms of their location and their propensity to cause severe disease. F. tularensis type A, for instance, is the most dangerous type and is only found in North America.

As its nickname suggests, tularemia normally affects animals such as rabbits, hares and rodents, but humans can also become infected. This can happen in several ways: through the bite of infected ticks or deer flies; by drinking contaminated water; or via physical contact with an infected animal, including being bitten. As few as 10 to 25 individual bacterial cells can cause tularemia infection in humans.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tularemia cannot be spread from person to person. People who participate in activities such as hunting, wildlife management, hiking and camping are at higher risk of tularemia than the average person.

Symptoms: The exact symptoms of tularemia in humans depend on where the bacteria enter the body, but infected individuals usually experience a fever up to 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 degrees Celsius).

If F. tularensis enters the body via the skin, infected people may also develop an ulcer at the site of infection, as well as swelling of their lymph nodes, particularly in the armpit or groin. People who eat or drink food or water contaminated with F. tularensis may develop a sore throat, mouth ulcers and tonsilitis, or inflammation of the tonsils.

In the most serious cases of tularemia, in which people inhale dust or aerosols containing F. tularensis, the disease may cause symptoms in the lungs, including chest pain, a cough and breathing difficulties. These symptoms can also arise if an F. tularensis infection in other parts of the body is not treated and the bacteria then spread to the lungs.

Treatments: Tularemia can be treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, meaning those that are capable of killing a wide variety of bacteria. This treatment can lower the death rate of the disease from between 5% and 15% to 2%. There is currently no vaccine against tularemia that is approved for use in the U.S.

People can take precautions to prevent tularemia, according to the CDC. These include using insect repellant while outdoors and wearing gloves when handling sick or dead animals.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)