What to know about Oropouche virus — the deadly fever that has reached the U.S.

Cases of "sloth virus" have been reported in the U.S. and Europe for the first time. But what is it?

As of Aug. 16, 2024, more than 20 cases of Oropouche virus disease — sometimes nicknamed "sloth virus" — have been confirmed in travelers returning to the U.S. from Cuba.

These are the first known cases in the U.S. of the viral disease, which normally circulates in parts of South America, Central America and the Caribbean. They join a further 19 cases that have also been detected for the first time in travelers returning to Europe from the Americas this summer.

So far, no one in the U.S. has died of the virus. However, health officials are warning people who wish to travel to areas where the virus spreads, especially pregnant women, to be extra vigilant.

Here's what we know so far about the so-called sloth virus.

Related: WHO declares mpox outbreak in Africa a global health emergency

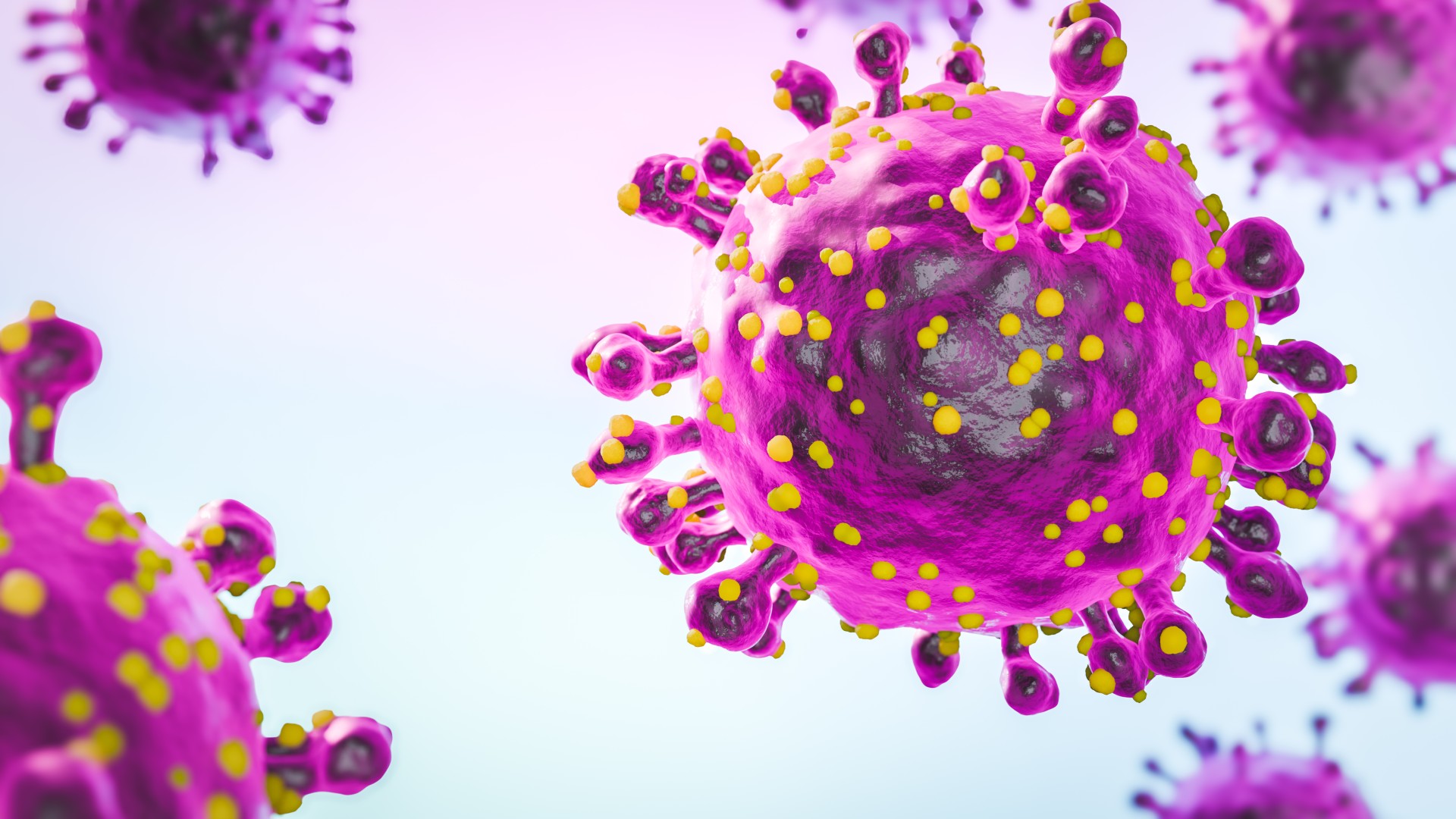

What is Oropouche virus?

Oropouche virus disease is a Zika-like illness that was first detected in a forest worker in Trinidad and Tobago in 1955.

Several media outlets have recently referred to the disease as "sloth virus" because scientists have proposed that the main animal host of the virus is the pale-throated sloth (Bradypus tridactylus). These sloths are thought to be a source of human infection transmitted by insect bites, and vice-versa.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, other researchers have proposed that other animals, such as wild birds or primates including capuchin (Cebus) and howler (Alouatta) monkeys, are actually the main animal host of the disease.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms of Oropouche virus disease are similar to those of dengue, chikungunya, Zika and malaria.

Symptoms usually begin around four to eight days after a person is infected by a disease-carrying insect. They include sudden-onset fever, headache, joint stiffness, pain and chills, which generally last for between five and seven days. Sometimes, patients may also experience persistent nausea and vomiting.

Fewer than one in 20 patients develop severe disease, including inflammation around the spinal cord and brain (meningitis) or inflammation of the brain (encephalitis).

The disease is rarely fatal, however, two deaths from severe disease have been recently reported in Brazil. Most patients recover within a week of contracting the disease, but some may take weeks to recover.

How is the virus transmitted?

People catch Oropouche virus from a biting fly called a midge. The midge species, Culicoides paraensis, that typically transmits the virus is found in forests and around bodies of water, such as lakes and ponds. These midges live throughout the Americas, including several states in the U.S., but have not been found in Europe.

The disease can also be transmitted to humans by some species of mosquito, such as certain Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. As of yet, direct human-to-human transmission has not been reported.

Where have cases been reported?

Over the past 60 years, more than 30 epidemics of Oropouche virus disease, which collectively have caused more than half a million cases, have been reported in Brazil, Peru, Panama and Trinidad and Tobago.

This year Oropouche virus disease outbreaks have occurred in Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia and Peru. Cuba also reported its first-ever known cases in June 2024. The disease could spread even further, as climate change creates more favorable conditions for this to happen.

All recorded cases in the U.S. so far have been in travelers returning from Cuba: 20 in Florida and one in New York. Most patients have had a "self-limiting" illness that resolved on its own without treatment, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, at least three patients have experienced their symptoms come back after their initial illness was resolved, the CDC says.

Of the 19 known imported cases of Oropouche virus disease in Europe recorded in June and July 2024, 18 were in travelers returning to the continent from Cuba, while the other was in traveler from Brazil. Twelve of these cases were recorded in Spain, five in Italy and two in Germany.

Related: Rare meningitis and bloodstream infections on the rise in the US, CDC warns

What treatments are available?

There are no treatments or vaccines available for Oropouche virus disease. However, the CDC recommends that symptoms of the disease are treated by drinking fluids to prevent dehydration, staying well-rested and taking over-the-counter pain medications such as acetaminophen to curtail fever and pain.

Are pregnant women particularly vulnerable?

Health officials are investigating whether, like Zika, infection with Oropouche virus disease can cause poor outcomes during pregnancy, such as miscarriage and stillbirth.

In July 2024, the Brazilian Ministry of Health reported six possible cases of Oropouche virus disease being transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy. These have been tied to incidences of microcephaly — meaning the baby's head is smaller than average — and miscarriage. This is worrisome because microcephaly, which is associated with problems relating to physical and intellectual abilities, is a known risk when a person becomes infected with Zika during pregnancy.

However, there is not yet enough data to confirm that Oropuche is causing microcephaly.

"We want to be at high alert and respond quickly to make sure that we are protecting the health of pregnant moms everywhere," Dr. Mandy Cohen, director of the CDC, told CBS News.

How can I avoid becoming infected?

Most public health advice is currently centered around preventing insect bites while traveling to areas where the virus spreads. This includes using Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) - registered insect repellent, wearing light-colored long-sleeved shirts and long pants while outside, and using Insecticide-treated bed nets in rooms that do not have adequate air conditioning or window or door screens.

Pregnant travelers should disclose details about their plans with their healthcare provider, and reconsider "non-essential" travel to high-risk areas, such as Cuba, the CDC says.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)