Strange 'heartbeat' signal spotted coming from deep space

It's probably not aliens.

Astronomers have detected a mysterious radio signal that is pulsing rhythmically "like a heartbeat" in deep space.

The signal, named FRB 20191221A, is a fast radio burst (FRB) — an intensely strong flash of radio waves — coming from an unknown point of origin.

Most FRBs last only a few milliseconds at most, but the new signal is much longer — about 3 seconds — making it the longest FRB ever discovered. Moreover, it produces bursts of radio waves that repeat every 200 milliseconds, in a heartbeat-like rhythm, making it the FRB with the clearest periodic pattern ever detected. The researchers published their findings July 13 in the journal Nature.

Related: Weird type of fast radio burst discovered 3 billion light-years away

Fast radio bursts discharge more energy in a few milliseconds than the sun does in a year. Astronomers have long puzzled over the source of these sudden, bright flashes. But because FRBs erupt predominantly from galaxies millions — or even billions — of light-years away, and flare quickly and often only once, scientists have struggled to identify the sources of these bursts.

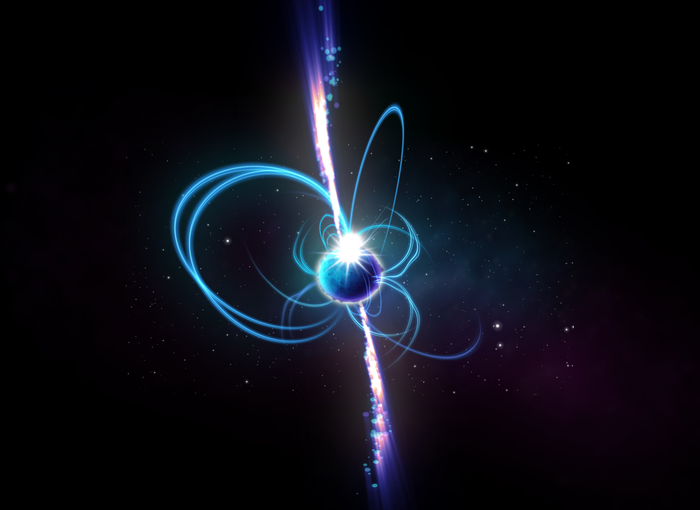

In 2020, the first-ever detection of an FRB within our own Milky Way galaxy enabled scientists to trace the FRB's origins to a magnetar, a highly magnetized, fast-rotating husk of a dead star. Magnetars, and their less magnetized cousins pulsars, are special types of neutron stars, which are ultradense stellar corpses left behind from the explosive deaths of stars. Pulsars and magnetars have unusually strong magnetic fields that are often millions or trillions of times more powerful than Earth's, and as they spin rapidly in space, they sweep out a beam of intense electromagnetic radiation from their poles, like giant lighthouses. But scientists aren't sure that all FRBs come from magnetars.

While most FRBs are one-time events, some repeat — sometimes in a single brief burst and other times across multiple periods.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There are not many things in the universe that emit strictly periodic signals," study co-author Daniele Michilli, an astrophysicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said in a statement. "Examples that we know of in our own galaxy are radio pulsars and magnetars, which rotate and produce a beamed emission similar to a lighthouse. And we think this new signal could be a magnetar or pulsar on steroids."

The astronomers first spotted the new signal using the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME), a radio telescope designed to spot radio waves emitted by hydrogen at one of the earliest stages of the universe — when mysterious, hypothetical dark energy first caused the universe to begin expanding at an accelerating rate. On Dec. 21, 2019, while scanning the skies for distant hydrogen radio emissions, CHIME picked up the strange signal.

"It was unusual," Michilli recalled. "Not only was it very long, lasting about 3 seconds, but there were periodic peaks that were remarkably precise, emitting every fraction of a second — boom, boom, boom — like a heartbeat. This is the first time the signal itself is periodic."

After analyzing the pattern produced by the signal's radio bursts, the researchers found that its emissions closely matched those seen from radio pulsars and magnetars spotted in our own galaxy. But there was one key difference: FRB 20191221A seems to be a million times brighter, according to the scientists.

They aren't sure what could be behind this intense luminosity, but they proposed that it could be caused by a source that is usually not as bright but, for some unknown reason, fired off a succession of brilliant bursts that CHIME happened to catch.

"CHIME has now detected many FRBs with different properties," Michilli said. "We've seen some that live inside clouds that are very turbulent, while others look like they're in clean environments. From the properties of this new signal, we can say that around this source, there's a cloud of plasma that must be extremely turbulent."

To learn more about the bursts and their mysterious source, the researchers are now preparing to hopefully catch additional pulses from FRB 20191221A. Doing so would help the team investigate what might be causing the pulses and learn more about the unexpected behaviors of neutron stars.

"This detection raises the question of what could cause this extreme signal that we've never seen before and how can we use this signal to study the universe," Michilli said. "Future telescopes promise to discover thousands of FRBs a month, and at that point, we may find many more of these periodic signals."

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.