How Lumps on a Man's Heels Signaled a Rare Disease in His Brain

The man developed lumps on his Achilles tendon a decade before he was hospitalized for neurological problems.

Problems with the Achilles tendon, the thick band of tissue that connects the calf muscles to the heel bone, typically don't signal a brain condition. But for one man in China, lumps on the Achilles tendon were an early sign of a serious metabolic disease that affected his brain.

The 27-year-old man was hospitalized after he developed neurological symptoms, including a change in his personality, according to a report of the case, published yesterday (Oct. 21) in the journal JAMA Neurology. He became irritable and hyperactive and had problems with his memory, according to the authors, from The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in Chongqing, China.

Two years before his hospitalization, the man developed glassy eyes and lethargy, and about a decade ago, he developed painless masses on both his Achilles tendons that were 2 inches (5 centimeters) in diameter, the report said.

Related: 27 Oddest Medical Case Reports

At his hospitalization, doctors at Chongqing Medical University noticed that the man still had painless lumps on both his Achilles tendons, but the lumps were now larger, about 3 inches (8 cm) in diameter. He also had trouble maintaining balance while walking in a straight line.

Lab tests additionally revealed that the levels of fat in his blood, called triglycerides, were unusually high — more than double the normal level.

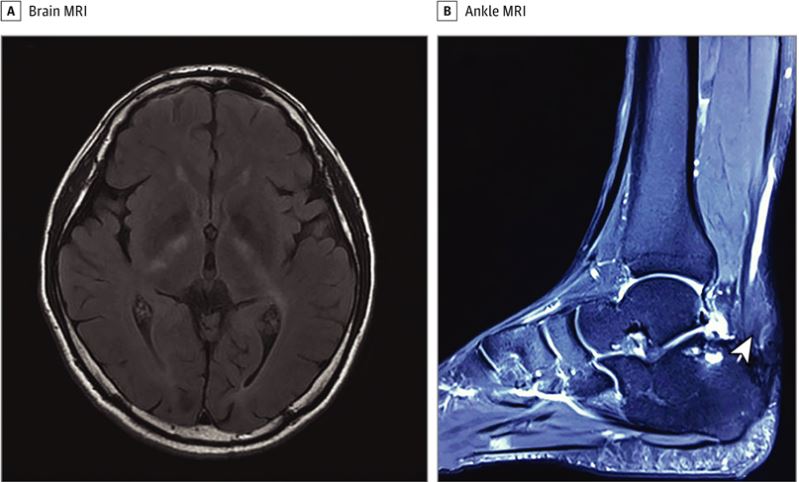

An MRI of his ankles showed enlargement of his Achilles tendons, and an MRI of his brain also showed abnormalities, the report said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A genetic test finally led to the man's diagnosis: He had cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, a rare genetic condition in which a person's body cannot effectively break down fats such as cholesterol, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH)'s Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). This leads to the development of fatty growths, called xanthomas, in the body, especially in the brain and tendons.

The condition often causes progressive neurological problems, including dementia and difficulty with movement, as well as behavioral changes, including agitation, aggression and depression. It can also cause cataracts and mental impairment, GARD says.

The disorder is caused by mutations in a gene called CYP27A1, which produces an enzyme involved in breaking down cholesterol, according to the NIH. This condition is estimated to affect about 1 in a million people worldwide, the NIH says.

Some symptoms can appear as early as infancy or childhood, but the signs are often missed or patients are given the wrong diagnosis; as a result, the true diagnosis can be delayed up to 25 years, the report said.

The condition is often treated with a medication called chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), which can reduce cholesterol levels. However, even with treatment, patients' neurological symptoms often worsen over time, the authors of the case report said.

In the current case, the man experienced some improvement in his glassy eyes after 18 months of treatment and the size of his brain lesions also decreased slightly, the report said. But his symptoms of agitation and hyperactivity remained the same, and he is now bedridden and unable to care for himself, the report's authors said.

They concluded that "early diagnosis and intervention are key factors" in the outlook for patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis.

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain

- 5 Diets That Fight Diseases

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About Fat

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.