Scythelike jaws of Cretaceous 'hell ant' clutch a baby cockroach in an amber tomb

Vertical-swinging jaws trapped prey against the ant's horn.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

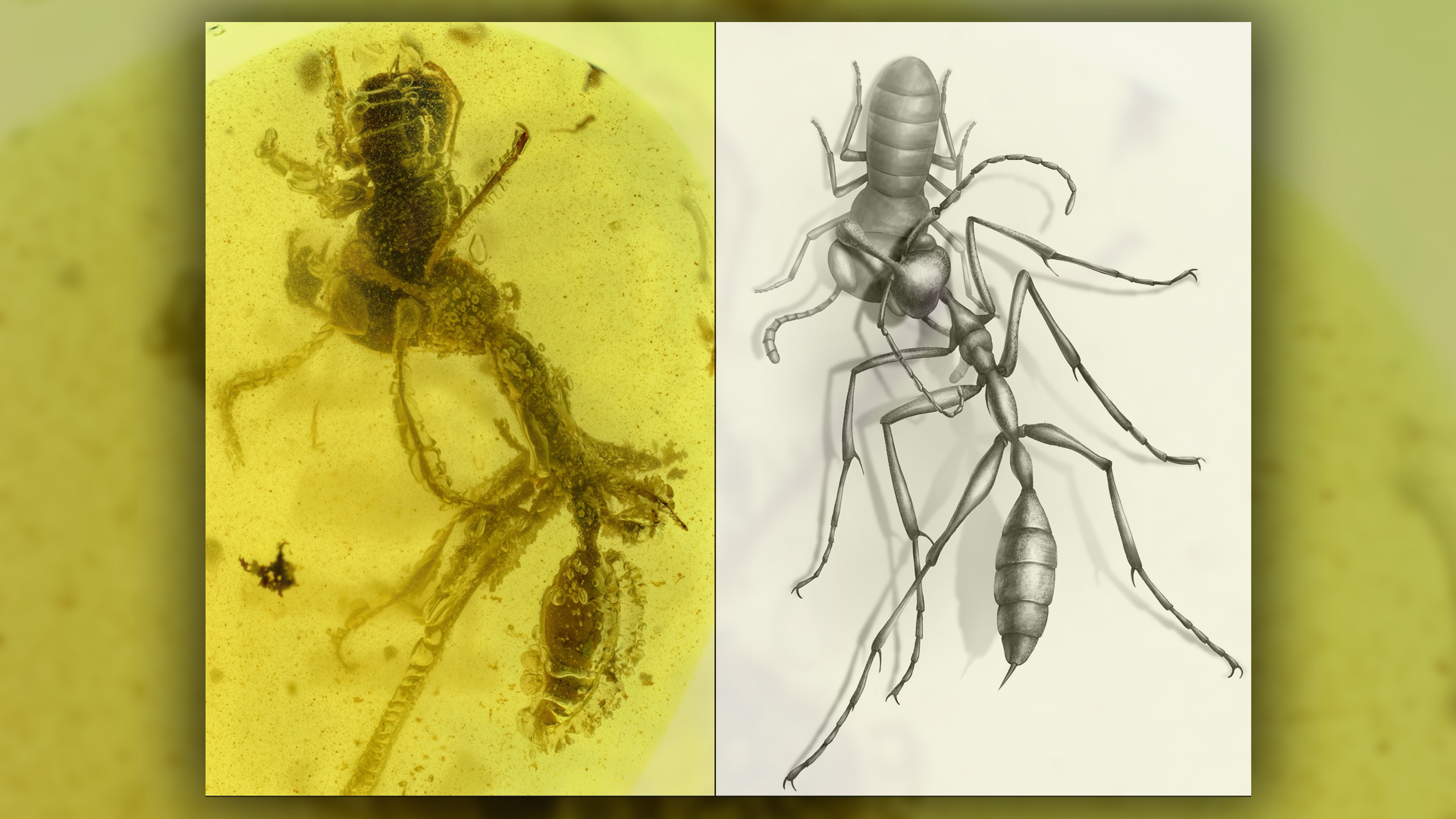

Around 99 million years ago, a juvenile cockroach met a hellish fate. It was snapped up by the jaws of a Cretaceous hell ant, a fierce predator with long, curving mandibles that swept up toward the top of the ant's head.

Just moments later, the ant and roach were trapped in sticky sap that eventually turned to amber, providing scientists with a first glimpse of how the weird-faced ants trapped prey.

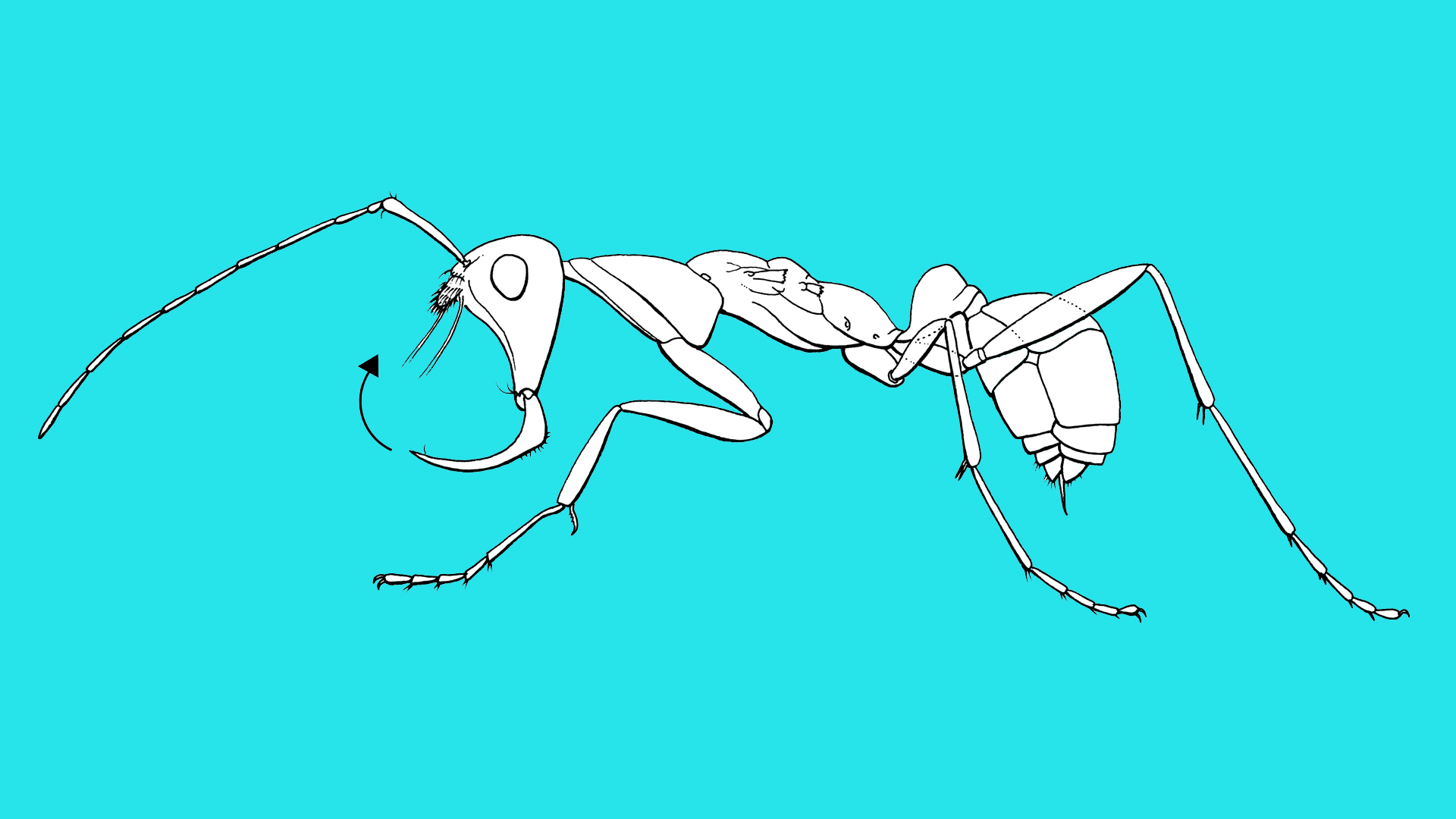

The profile of a hell ant, with exaggerated upward-facing jaws that arc like the Grim Reaper's scythe, is unlike that of any ant alive today. Adding to the facial weirdness is a hell ant's horn, which comes in a variety of shapes in this ant group, known as Haidomyrmecine.

Researchers had long suspected that hell ants swung their prominent mandibles upward to catch their prey, unlike modern ants that snap their jaws together horizontally. In the piece of Cretaceous amber from Myanmar, scientists found the first confirmation of this hunting technique.

Related: Photos: Ancient ants & termites locked in amber

Hell ants lived during the Cretaceous period (about 145.5 million to 65.5 million years ago), and are known from amber deposits in Myanmar, France and Canada spanning 100 million to 78 million years ago, said evolutionary biologist Phillip Barden, an assistant professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. Barden and his colleagues described the amber-embedded hell ant in a new study, published online today (Aug. 6) in the journal Current Biology.

Scientists described the first hell ant about a century ago, and have since identified 16 species — all of whom have elongated mandibles and horns.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the amber, the mandibles of the hell ant Ceratomyrmex ellenbergeri hug the roach nymph, Caputoraptor elegans, from below, pinning it against the horn on the ant's head. Finding this rare example of fossilized predation was astonishing — but also vindicating, Barden told Live Science.

"When we first started working on hell ants in 2011 to 2012, it looked like the only way they could have fed was by moving their mouth parts vertically," Barden said. At the time, the notion was "a little contentious," but this little hell ant showed their hypothesis was correct, he said.

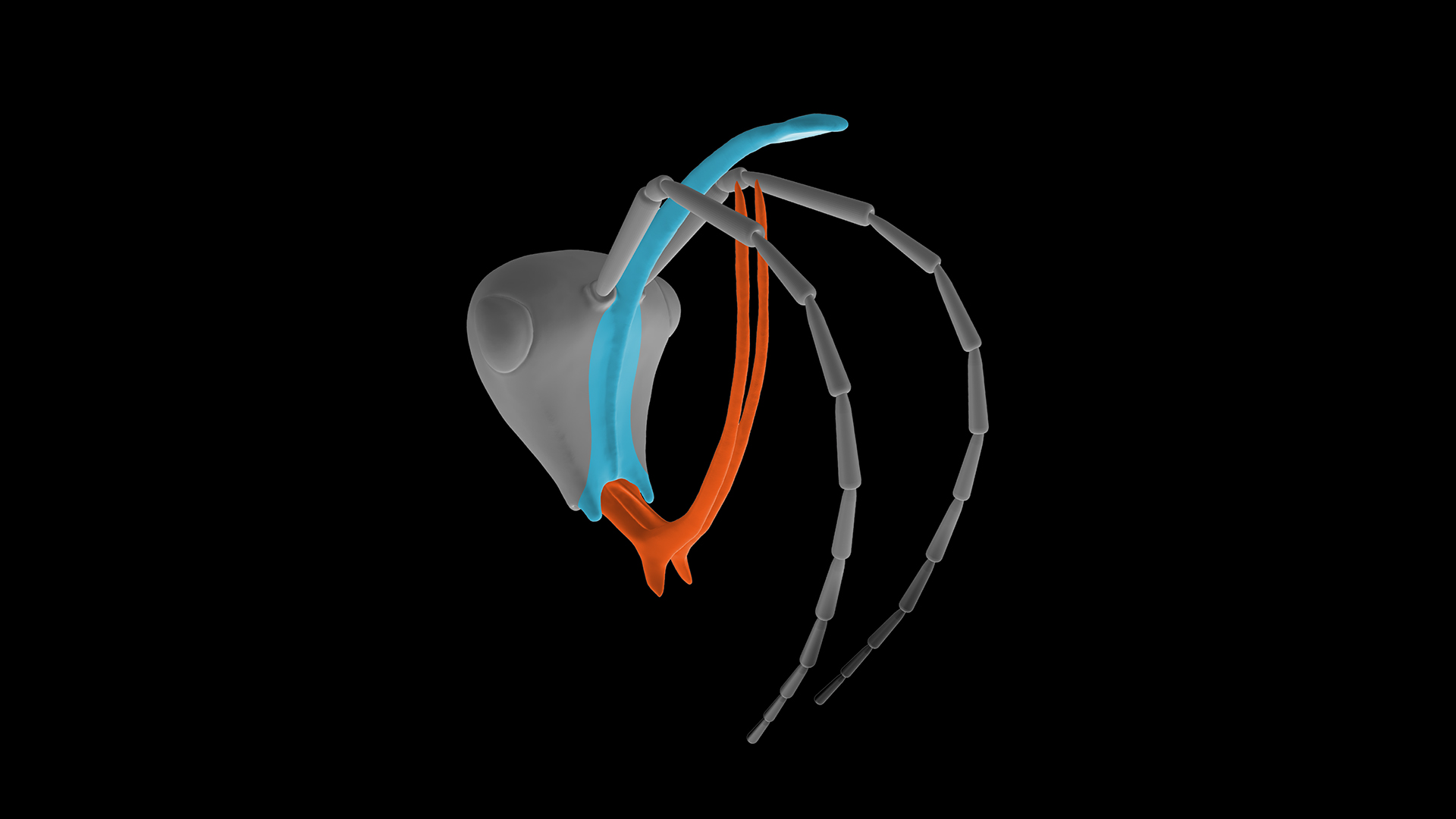

The researchers also digitally modeled the heads of Ceratomyrmex and other hell ants in 3D, comparing them to both modern and extinct ants. Their analysis of the evolutionary relationships between the groups confirmed that hell ants were among the earliest known ants, according to the study.

Social digestion

The amber-trapped hell ant never got to eat the roach. However, Barden offered some diabolical possibilities for how that meal may have unfolded.

"First thing would probably be that the ant would have stung the prey to paralyze it," he said. And how would it have eaten the roach? "We originally thought that all the hell ants would have pierced their prey and drunk the hemolymph, which is like insect blood," Barden said. However, while some hell ant species have horns that are reinforced for piercing, Ceratomyrmex's horn was holding the nymph in place but not piercing it.

The best potential explanation, Barden told Live Science, comes from the feeding habits of a modern ant from Madagascar called the Dracula ant (Adetomyrma venatrix), which also has oddly-shaped mandibles.

"They have these highly specialized mouthparts that are so exaggerated they can't feed themselves," Barden explained. "Instead, they feed the prey to their own larvae — and the larvae have unspecialized mouthparts, so they can chew normally."

Once the larvae are fed, what happens next truly seems like a scene from hell. Adult ants pierce the larvae's sides and they drink the hemolymph of their own offspring and siblings, a charming practice called non-destructive cannibalism, Barden said.

"Basically, they use their own siblings and offspring as a social digestive system," he said. "We don't have direct evidence that's the case here, but that could be something that's going on."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus