Herodotus lied about famous Greek battle against Carthage, new study finds

It turns out the Greeks used mercenaries.

Herodotus, the famed ancient Greek historian, lied about a pivotal battle between the Greeks and the Carthaginians, a new study finds.

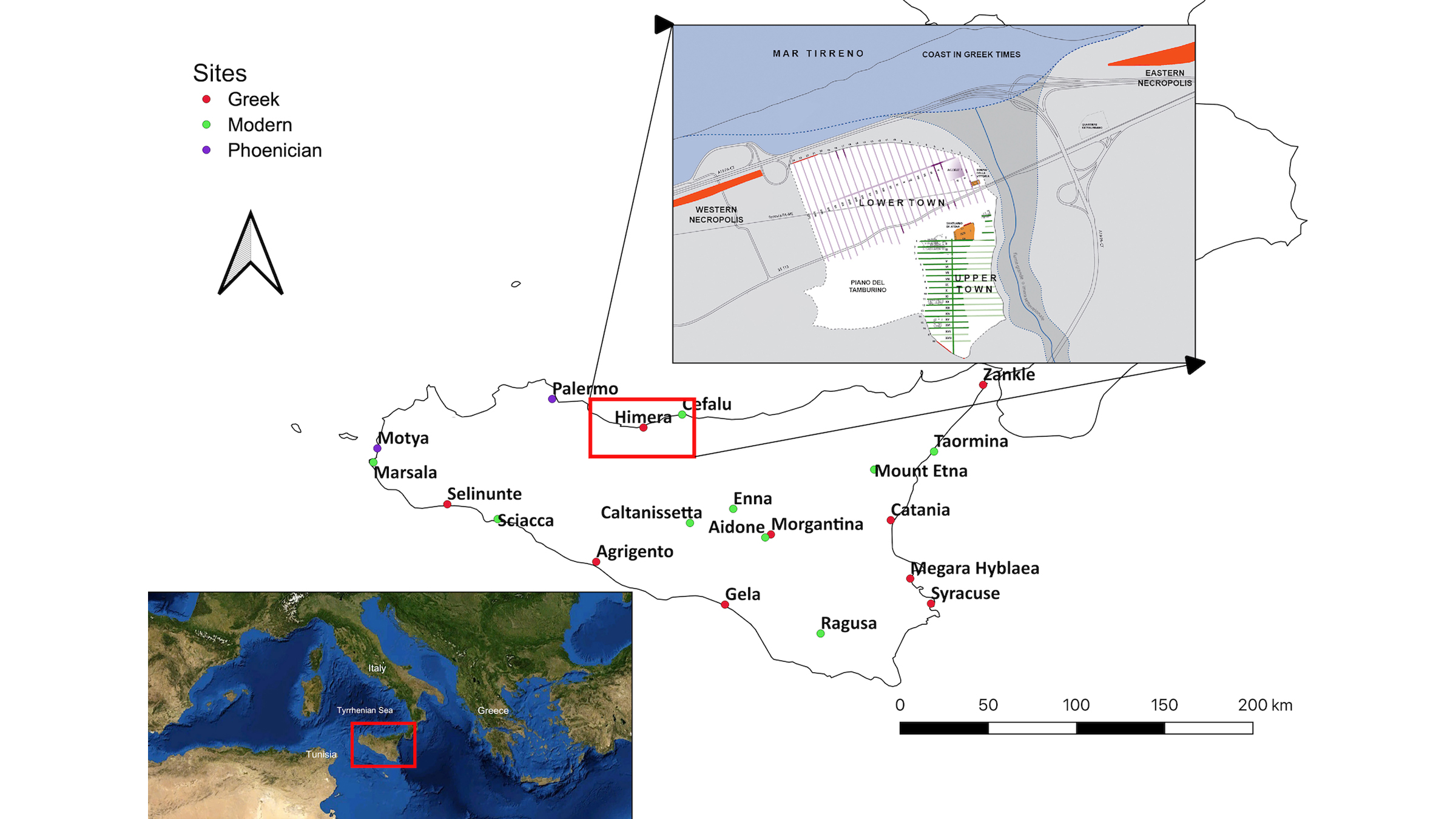

In his magnum opus "The Histories," Herodotus detailed the First Battle of Himera on Sicily in 480 B.C. He wrote that when the "barbarian" Carthaginians attacked the Greek colony of Himera, a coalition of Greek allies from other Sicilian cities joined the fray, leading to a Greek victory.

But now, a chemical analysis of the bones of the soldiers who fought at the First Battle of Himera reveals that those Greek "allies" were actually foreign mercenaries, likely hired by the Greeks to help vanquish their foes.

"We realized that it was possible that many of the soldiers from 480 [B.C.] were coming from outside of Sicily, and maybe even outside of the Mediterreanean," study lead researcher Katherine Reinberger, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Georgia, told Live Science.

Related: Photos: Ancient Greek burials reveal fear of the dead

Several decades later, in 409 B.C., the Second Battle of Himera erupted between the Greeks and Carthaginians, but this time the Carthaginians won. Herodotus had died by that time, but another ancient Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus (whose name means Diodorus of Sicily), wrote about it, as well as the first battle. While Diodorus Siculus also omitted the Greeks' use of mercenaries during the First Battle of Himera, he accurately described the second, saying that local Greeks at Himera fought but lost the battle. This account is corroborated by a new chemical analysis of those soldiers' remains, Reinberger said.

The new research suggests that "in general, [these two ancient historians] are trying to be accurate in their accounts," Reinberger said. "However, as we have to with modern sources of information, we have to evaluate them and use other available evidence to think critically about how accurate they are and why they may have emphasized or omitted certain pieces of information."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ancient mass graves

In 2008, Italian archaeologists discovered ancient mass graves in Himera filled with the remains of 132 soldiers, some with weapons still embedded in their bones, dating to 480 B.C. and 409 B.C. The deceased were buried in orderly rows, and archaeologists think this indicates that these soldiers fought for Himera and were intentionally buried "by Greek victors who had time and opportunity to respectfully bury their own dead," the researchers wrote in the new study.

This find caught the attention of the Bioarchaeology of Mediterranean Colonies Project (BMCP), co-led by study researchers Laurie Reitsema, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Georgia, and Britney Kyle, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Northern Colorado, because they were interested in the ancient soldiers who fought for the Greek colonies.

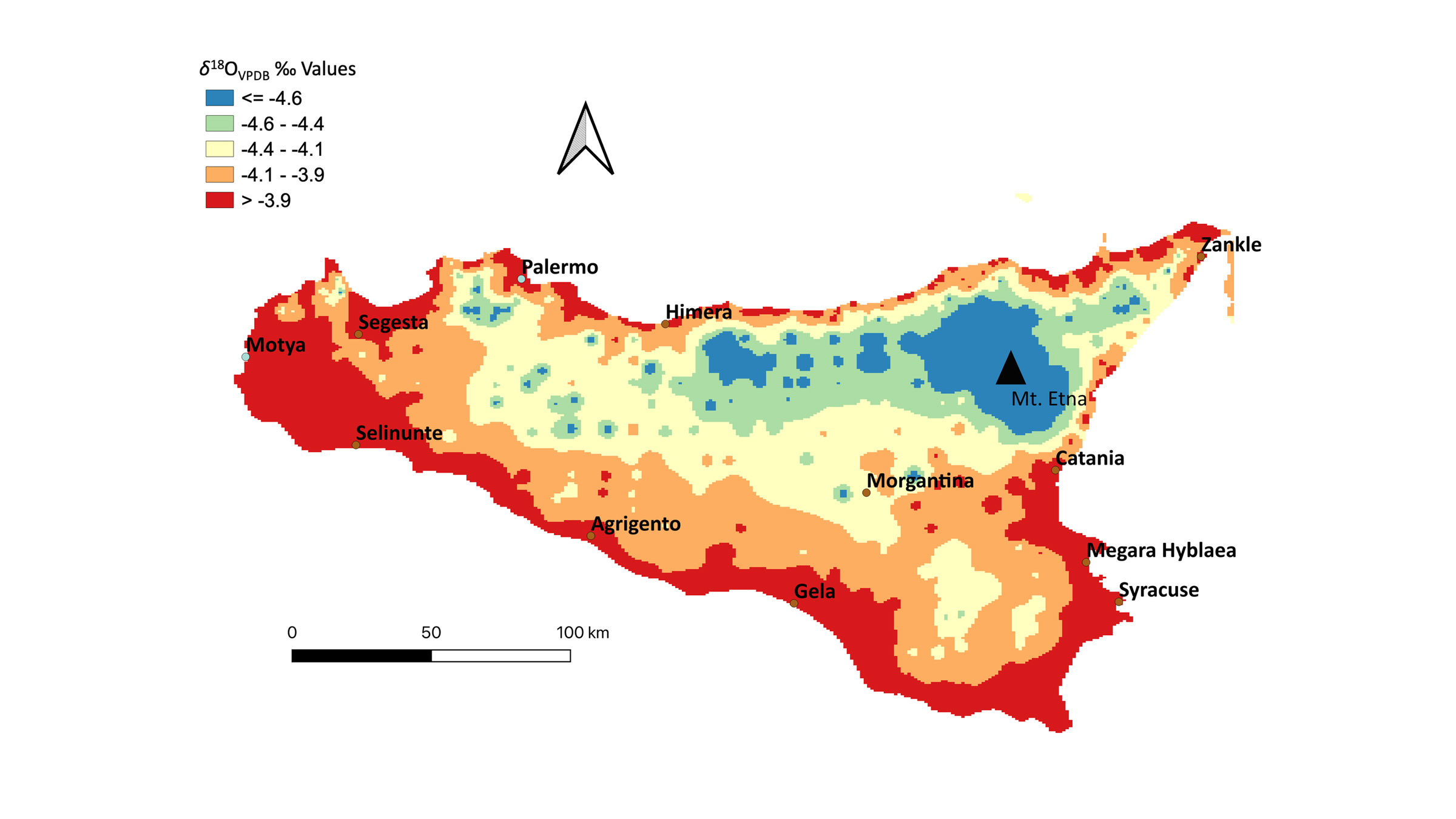

Working with BMPC, Reinberger analyzed where these soldiers came from. She examined the soldiers' bones using a technique that looks at different versions of elements — in this case strontium and oxygen — that have a different number of neutrons in their nuclei, known as isotopes. Over time, oxygen from the water people drink and strontium from the food they eat ends up in their tooth enamel. By comparing the isotope ratios in the teeth with those found in the landscape, researchers can determine where individuals grew up.

The team analyzed isotopes in the tooth enamel of 62 soldiers — 51 from 480 B.C. and 11 from 409 B.C. — as well as 25 ancient individuals from the general population of Himera, found at a nearby cemetery. The soldiers from the First Battle of Himera had highly variable isotopic values, much more so than the general population samples, meaning they grew up in many different places, the researchers found. Overall, about two-thirds of the soldiers from 480 B.C. were not local to Sicily. This suggests that "Greek tyrants [in Sicily] hired foreign mercenaries from more distant places," during the First Battle of Himera, the researchers wrote in the study.

Related: 10 ancient battles that changed history

It's a mystery where these mercenaries came from, but locations with similar strontium isotopic ratios to some of the ones found in the bones include the Greek Cyclades islands in the Aegean, and Catalonia, Spain, the researchers said. The soldiers' oxygen isotope values suggest that they came from areas farther inland and at higher elevations than coastal Sicily, including the ancient Greek cities of Himera, Agrigento and Syracuse, the team found.

Determining the exact location of where the soldiers came from may prove challenging, said Rasmus Andreasen, an isotope geochemist at the Department of Geoscience at Aarhus University in Denmark, who was not involved with the study.

"There's not a whole lot of variation geologically in the Mediterranean area, so there's a lot of places that could be a potential match," Andreasen told Live Science. "It's not a signature that's unique to one place, so you can't use it to say, 'Oh, they definitely came from here.' You can safely say that they did not come from Himera, but where they came from is more open to interpretation."

Meanwhile, just one-fourth of the soldiers whose remains were unearthed from the second battle were not local, indicating that the historical records about the second battle were accurate, the team found.

Why did Herodotus lie?

Himera sits in northern Sicily, a strategic spot for trade in the Mediterranean. That's likely why the Greeks founded a colony there in about 648 B.C. The Phoenicians also had colonies in Sicily, and they often traded with Greek colonies there, Reinberger noted. It's not clear why tensions arose between the Greeks and Phoenicians from the city-state of Carthage during the First Battle of Himera, but one idea is that it was related to political unrest from Greek tyrants, while another is that the Persians, who were already fighting the Greeks in the Persian Wars, conspired with the Carthaginians to attack Greek Sicily, Reinberger said.

In "The Histories," Herodotus states that the Carthaginians used mercenaries when they attacked Himera, but neither he nor Diodorus Siculus mention foreign mercenaries on the Greek side. There might be a reason for this: Greek pride.

"I do think the ancient Greek historians had an interest in keeping the armies fully Greek," Reinberger said. "The Greeks were obsessed with being Greek." Herodotus' bias toward foreigners is evident in his writing. "He uses the term 'barbarian' a lot. In ancient Greece that just meant anyone who doesn't speak Greek," she added.

What's more, in some cases foreign mercenaries could gain citizenship by fighting for the Greeks. "Not all of the citizens of the Greek cities in Sicily were particularly happy about that because citizenship is tied up in independence and [owning land for] farming and the democratic nature of ancient Greek city states," Reinberger said. "I think there's at least one historical reference to Greeks being upset that there were some foreign mercenaries that were granted citizenship."

In their writings, Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus tie the First Battle of Himera to other Greek triumphs, writing that the victories at the Battle of Thermopylae and the Battle of Salamis happened on the same day, "as though heaven had deliberately arranged for the finest victory and the most famous of defeats to take place simultaneously," Diodorus said in a translated text. The stated timing is probably not factual, but shows just how much pride the Greeks had in their military forces, Reinberger said.

The new study has "pretty solid work," Andreasen said. "It's interesting that you can actually take the written records and match it up with the geological records."

The study was published online Wednesday (May 12) in the journal PLOS One.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.