Discovery of 'hidden world' under Antarctic ice has scientists 'jumping for joy'

The secret ecosystem was found more than 1,600 feet below the surface.

A never-before-seen ecosystem lurks in an underground river deep below the icy surface in Antarctica. Researchers recently brought this "hidden world" into the light, revealing a dark and jagged cavern filled with swarms of tiny, shrimplike creatures.

The scientists found the secret subterranean habitat tucked away beneath the Larsen Ice Shelf — a massive, floating sheet of ice attached to the eastern coast of the Antarctic peninsula that famously birthed the world's largest iceberg in 2021. Satellite photos showed an unusual groove in the ice shelf close to where it met with the land, and researchers identified the peculiar feature as a subsurface river, which they described in a statement. The team drilled down around 1,640 feet (500 meters) below the ice's surface using a powerful hot-water hose to reach the underground chamber.

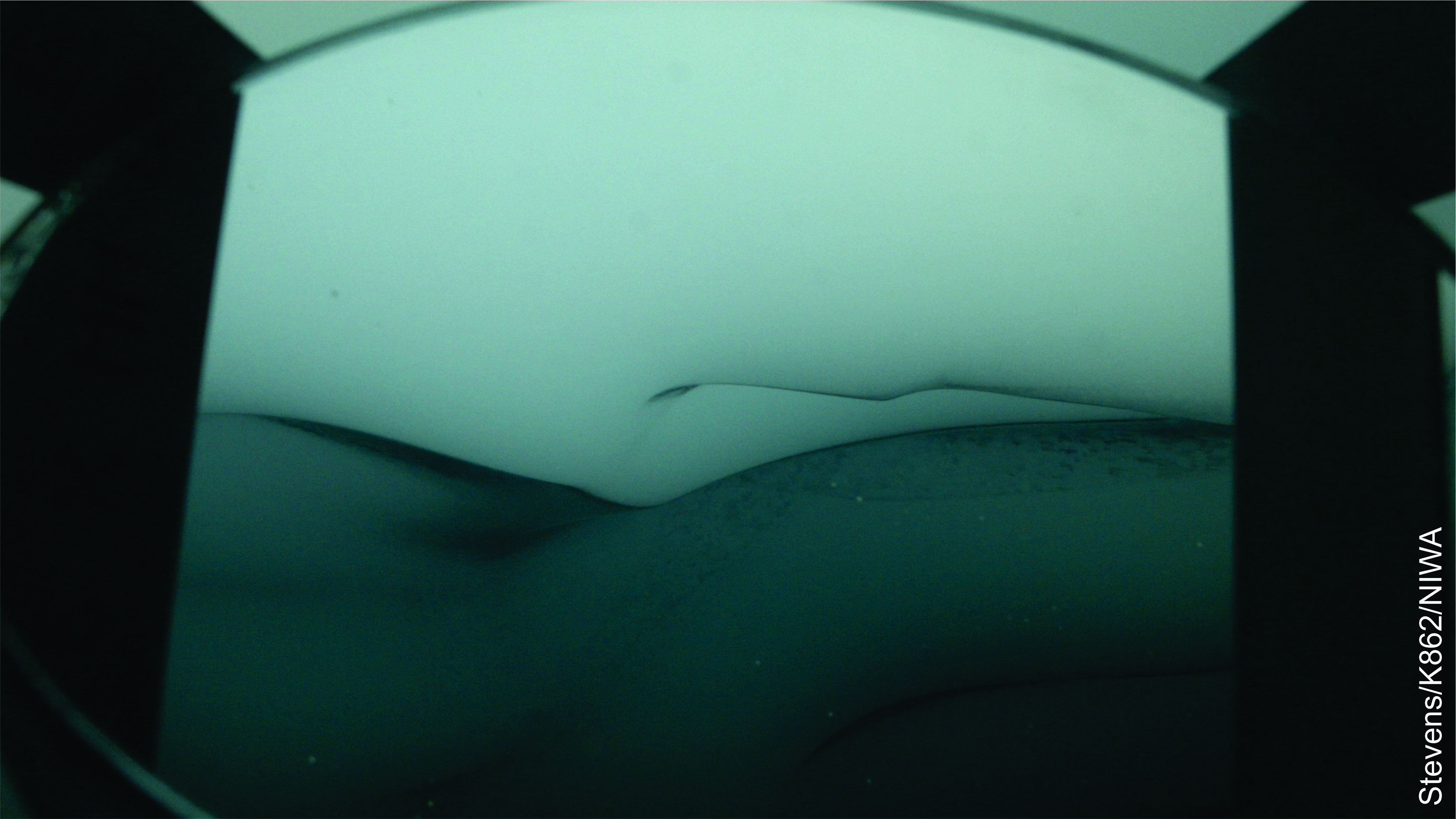

When the researchers sent a camera down through the icy tunnel and into the cavern, hundreds of tiny, blurry flecks in the water obscured the video feed. Initially, the team thought their equipment was faulty. But after refocusing the camera, they realized that the lens was being swarmed by tiny crustaceans known as amphipods. This caught the team off guard, as they had not expected to find any type of life this far below the icy surface.

"Having all those animals swimming around our camera means there’s clearly an important ecosystem process happening there," Craig Stevens, a physical oceanographer at the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) in Auckland, New Zealand, said in the statement. The discovery of the secret shrimp-infested structure had the team "jumping up and down for joy," Stevens added.

Related: Alarming heat waves hit Arctic and Antarctica at the same time

Experts have long suspected that there is a vast network of rivers, lakes and estuaries underneath Antarctica, but until now these features have been poorly studied. It was previously unknown if they harbored life, which makes the new finding even more important. "Getting to observe and sample this river was like being the first to enter a hidden world," lead researcher Huw Horgan, a glaciologist at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, told The Guardian.

Horgan first spotted hints of the subsurface structure in 2020 while looking at a satellite photo of the area. It was visible as a long depression, or groove, stretching across the ice — a hallmark of an underground river. However, despite being prominent in the satellite images, the groove initially eluded surface detection, Stevens said. "But then we found this tiny, gentle slope and guessed we’d got the right spot."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After sending the camera down into the river, the team was surprised to learn that the cavern looked drastically different from what they had predicted. The researchers had expected that the roof of the chamber would be smooth and flat. But instead, they found that the roof was very uneven and had lots of steep undulations. The cavern was also much wider nearer the roof. "It looked like a loaf of bread, with a bulge at the top and narrow slope at the bottom," Stevens said.

The researchers also unexpectedly discovered that the water column underground split into four or five distinct layers of water flowing in opposite directions. "This changes our current understanding and models of these environments," Stevens said. "We’re going to have our work cut out understanding what this means."

The team arrived above the buried river just in time to make another interesting observation. The researchers set up camp a couple of days before the record-shattering eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano in Tonga on Jan. 15. The massive explosion caused pressure waves that rang Earth's atmosphere like a bell, and sensors the researchers had placed on the ice's surface recorded similar pressure waves moving through the underground chamber. "Seeing the effect of the Tongan volcano, which erupted thousands of kilometres away, was quite remarkable," Stevens said. "It is a reminder about just how connected our whole planet is."

The scientists will continue to study the newfound subsurface ecosystem and hope to learn more about how the nutrients in the water are cycled through Antarctica's underground water networks to support the abundance of life that lives there.

However, the researchers also worry that even hidden ecosystems like this one may be at risk from rapidly warming temperatures caused by climate change. "The climate is changing, and some key focal points are yet to be understood by science," Steven said. "But what is clear is that great changes are afoot."

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.