This 'Blob' of Radiation Might Be a Long-Lost Neutron Star

The closest supernova to Earth is also one of the most mysterious.

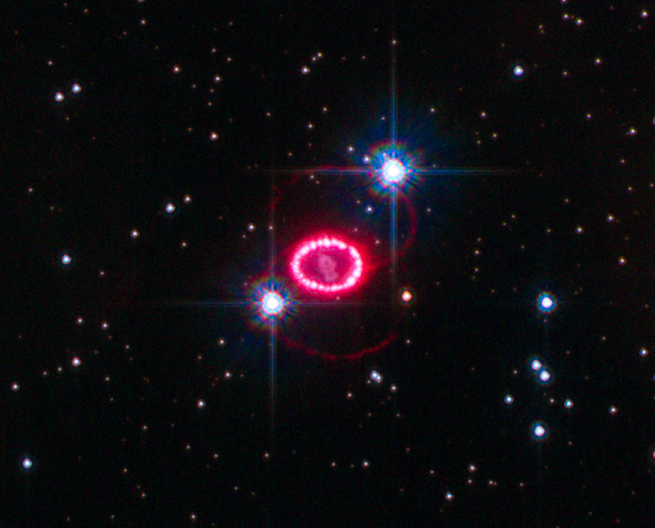

On Feb. 23, 1987, a ring of fire tore open the sky in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small galaxy that orbits ours some 168,000 light-years away. That night, a giant, blue star 14 times more massive than the sun erupted into a supernova explosion brighter and closer to Earth than any other seen in the last 400 years. (Scientists named that explosion "supernova 1987A," because apparently whimsy is as dead as that blue giant.)

In the 32 years since astronomers spotted the blast, a fog of gas and dust many solar systems wide spewed into space where the ex-star used to be. There, scientists have found one of the clearest-ever views of a violent stellar death and its dusty aftermath. One thing they never found, however, is the corpse of the star itself — until now.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope in Chile, a team of researchers peered into the dusty blast site and identified a "blob" of radiation that they believe conceals the remains of the once-mighty star responsible for supernova 1987A. According to a study published Tuesday (Nov. 19) in The Astrophysical Journal, the blob glows twice as brightly as the dust surrounding it, suggesting that the object conceals a powerful source of energy — possibly a superdense, brightly glowing stellar corpse known as a neutron star.

"For the very first time we can tell that there is a neutron star inside this cloud within the supernova remnant," lead study author Phil Cigan, an astrophysicist at Cardiff University in Wales, said in a statement. "Its light has been veiled by a very thick cloud of dust, blocking the direct light from the neutron star at many wavelengths, like fog masking a spotlight."

Researchers have suspected for years that a neutron star lurked behind the dusty fog of 1987A. To produce the sheer mass of gas seen there today, the progenitor star, at its prime, must have been nearly 20 times the mass of Earth's sun, and before running out of fuel and exploding, that star must have been around 14 times the sun's mass.

Stars that big can become so hot that protons and electrons at the stellar core combine into neutrons, flinging out a flood of tiny, ghostly subatomic particles called neutrinos in the process. Following such a star's explosive death, the core compresses into an uber-dense, incredibly fast-spinning ball of pure neutrons known as a neutron star.

Early observations of 1987A confirmed that lots of neutrinos were spilling out of the stellar wreckage. The bright glow of the surrounding dust cloud also suggested that an incredibly luminous object lay within. (Neutron stars that beam beacons of X-ray light out of their poles are known as pulsars and are some of the brightest objects in the sky.) However, the dust was too thick and too bright for astronomers to get a clear look inside.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To get around that obstacle, the authors of the new study used the powerful ALMA telescope to look at incredibly minute differences between light wavelengths inside 1987A. The analysis not only showed where some parts of the cloud were glowing brighter than others, but also allowed the team to infer what kinds of elements were present in the gas and dust.

They found a blob of brighter-than-average energy close to the cloud's center, coinciding with an area that had fewer CO (carbon monoxide) molecules than the rest of the supernova remnant. The authors said the CO is likely being destroyed by a source of high heat, likely the same source of radiation that is making the whole cloud shine. This conclusion suggests a bright, dense object that could very well be the corpse of the star that went supernova in 1987.

"We are confident that this neutron star exists behind the cloud and that we know its precise location," study co-author Mikako Matsuura, also of Cardiff University, said in the statement. Additional observations of the blob will reveal more about its nature; however, the real test will come 50 to 100 years from now. The researchers said that's when the dust should clear enough to reveal the violent engine underneath.

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

- 15 Unforgettable Images of Stars

- 9 Strange Excuses for Why We Haven't Met Aliens Yet

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.