High school students may have just discovered an 'impossible' proof to the 2,000-year-old Pythagorean theorem

Two high school seniors have presented their proof of the Pythagorean theorem using trigonometry — which mathematicians thought to be impossible — at an American Mathematical Society meeting.

Two high school students say they’ve proved the Pythagorean theorem using trigonometry — a feat mathematicians thought was impossible.

While the proof still needs to be scrutinized by mathematicians, it would constitute an impressive finding if true.

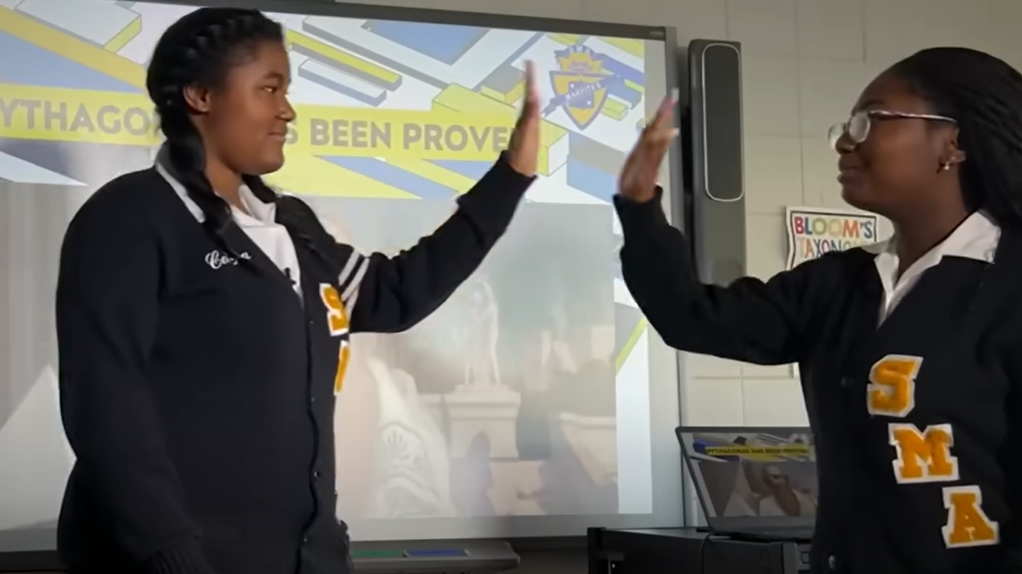

Calcea Johnson and Ne'Kiya Jackson, who are seniors at St. Mary's Academy in New Orleans, presented their findings March 18 at the American Mathematical Society’s (AMS) Spring Southeastern Sectional Meeting.

"It's an unparalleled feeling, honestly, because there's nothing like it — being able to do something that people don't think that young people can do," Johnson told the New Orleans television news station WWL. "You don't see kids like us doing this — it's usually, like, you have to be an adult to do this."

Pythagoras' 2,000-year-old theorem, which states that the sum of the squares of a right triangle's two shorter sides is equal to the square of the hypotenuse, is the basis for trigonometry. Trigonometry, which comes from the Greek words for triangle ("trigonon") and to measure ("metron"), lays out how the side lengths and angles in a triangle are related, so mathematicians thought that using trigonometry to prove the theorem would always include some hidden expression of the theorem itself. Thus, proving the theorem with trigonometry would constitute a failure of logic known as circular reasoning.

Remarkably, Johnson and Jackson say they can prove the theorem without using the theorem itself. Because the findings have not yet been accepted into a peer-reviewed journal, however, it's still too soon to say whether their proof will ultimately hold up.

Related: Mathematicians make rare breakthrough on notoriously tricky 'Ramsey number' problem

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In their abstract, Johnson and Jackson quote from a 1927 book by the American mathematician Elisha Loomis (1852 to 1940) called "The Pythagorean Proposition," which contains the largest known collection of proofs of the theorem — 371 solutions, according to research published in the Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing. "There are no trigonometric proofs, because all the fundamental formulae of trigonometry are themselves based upon the truth of the Pythagorean Theorem,” Loomis wrote.

But "that isn't quite true," the teenagers wrote in the abstract. "We present a new proof of Pythagoras’s Theorem which is based on a fundamental result in trigonometry — the Law of Sines — and we show that the proof is independent of the Pythagorean trig identity sin2x+cos2x=1." In other words, the high school seniors said they can prove the theorem by using trigonometry and without circular reasoning.

"It is unusual for high school students to present at an AMS Sectional Meeting," Scott Turner, director of communications at AMS, told Live Science in a prepared statement.

Despite their young age, the AMS has encouraged the high schoolers to submit their findings to a scientific journal. "Following their conference presentation, their next step would be to look into submitting their work to a peer-reviewed journal, where members of our community can examine their results to determine whether their proof is a correct contribution to the mathematics literature," Catherine Roberts, executive director at AMS, said in the statement.

Johnson and Jackson's achievement has not gone unnoticed in math circles. "We celebrate these early career mathematicians for sharing their work with the wider mathematics community and we encourage them to continue their studies in mathematics," Roberts added.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.