Fungi that cause lung infections may be lurking in the soil of most US states

A study hints that soil-borne fungi that can cause disease may be widespread in the U.S.

Soil-borne fungi whose spores can cause severe lung infections may be far more widespread in the U.S. than experts thought, a new study suggests.

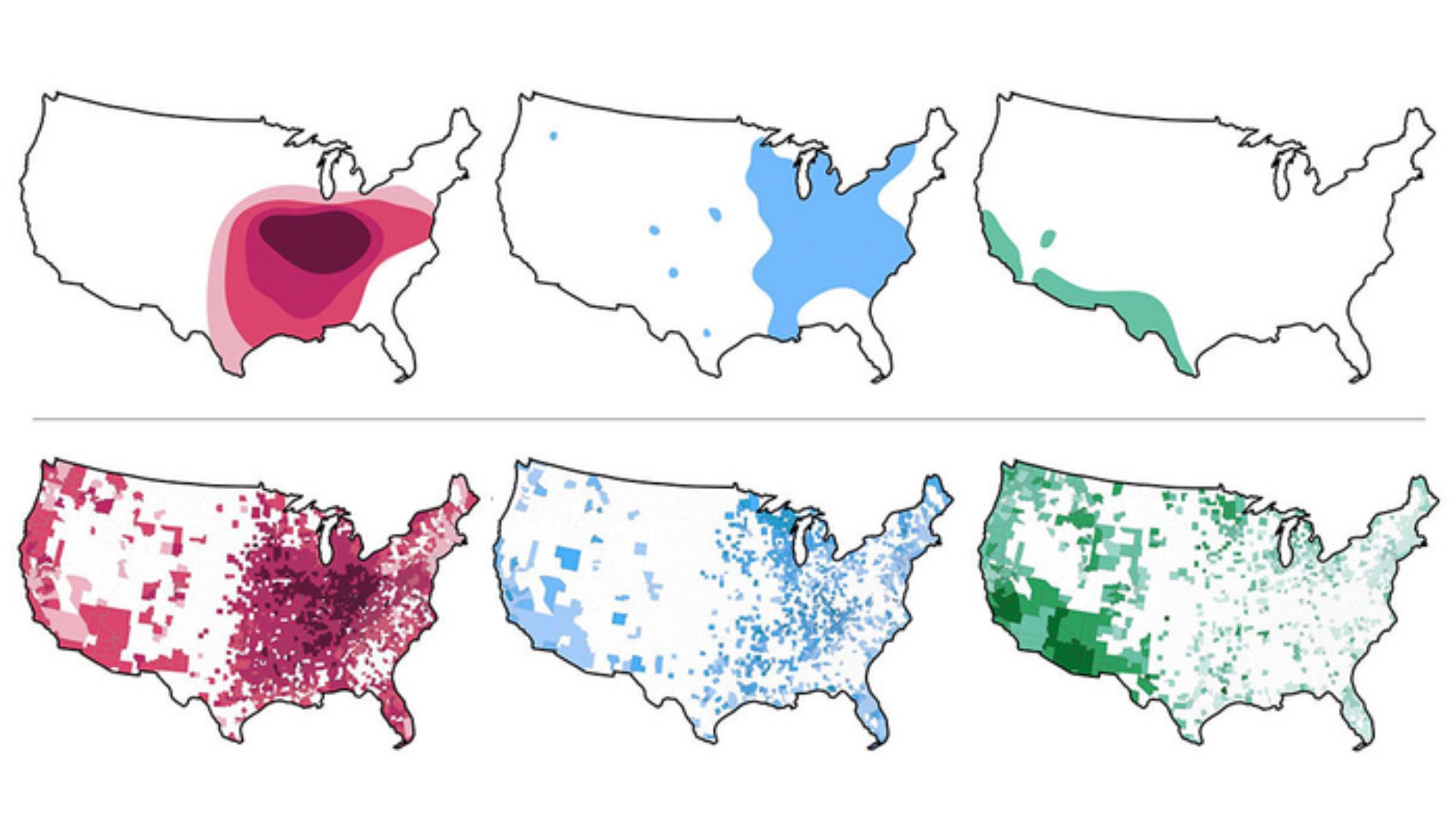

These fungi include Histoplasma, known as histo for short, which is a genus of fungus that causes histoplasmosis. Authoritative sources, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the online medical resource StatPearls, state that the fungi can be found in central and eastern U.S. states, particularly in areas near the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys.

However, according to the new research, Histoplasma can likely be found in 47 U.S. states, plus Washington, D.C., and is growing at clinically significant levels in at least one county per affected state.

"Every few weeks I get a call from a doctor in the Boston area — a different doctor every time — about a case they can't solve," senior study author Dr. Andrej Spec, an associate professor of medicine and a specialist in fungal infections at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, said in a statement. "They always start by saying, 'We don't have histo here, but it really kind of looks like histo.' I say, 'You guys call me all the time about this. You do have histo.'"

Related: Fungi grow inside cancerous tumors, scientists discover

The new study, published Nov. 11 in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, analyzed Medicare fee-for-service claims made between 2007 and 2016 to determine the rate of fungal infection diagnoses in the 50 states and D.C. The team included data only from Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older, so it's not a complete picture of all the fungal infections in each state, the study authors noted.

In addition to histo, the team specifically looked for cases of blastomycosis, an infection caused by fungi in the genus Blastomyces, and valley fever or coccidioidomycosis, which is caused by fungi in the genus Coccidioides. Historically, Blastomyces has been found in Midwestern, South Central and Southeastern states, and around the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River, according to the CDC. Coccidioides has been detected in the southwestern U.S. and south central Washington, the agency says.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When soil is disturbed, fungi in these genera release microscopic spores into the air. Most people don't get sick from inhaling the spores. However, some develop symptoms — such as fever, cough and night sweats — that resolve without medical treatment, and some develop severe lung infections that can then spread to other body parts, according to the CDC.

People with weakened immune systems face a high risk of severe infection from all three genera. In the case of histo, infants and adults older than 55 years old also have a high risk of serious disease, and for Valley Fever, the same is true for people who are pregnant or have diabetes.

Considering the 50 states and D.C., more than 90% of jurisdictions had histo, while 69% and 78% had at least one county with significant rates of coccidioidomycosis and blastomycosis, respectively, the team found.

To determine where the diagnoses took place, the team took beneficiaries' home addresses into account and assumed that they'd picked up the infections in their counties of residence. This is a limitation of the study, as it doesn't account for travel-related exposures, the authors noted. This is especially relevant because, depending on the infection, a person's symptoms may emerge weeks to months after they breathe in fungal spores, giving them plenty of time to hop state lines.

But regardless of its limitations, the study hints that these fungi lurk in far more states than experts once thought, and doctors should recognize the potential for these illnesses to crop up all across the country, the study authors concluded.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

What are mRNA vaccines, and how do they work?

Deadly motor-neuron disease treated in the womb in world 1st