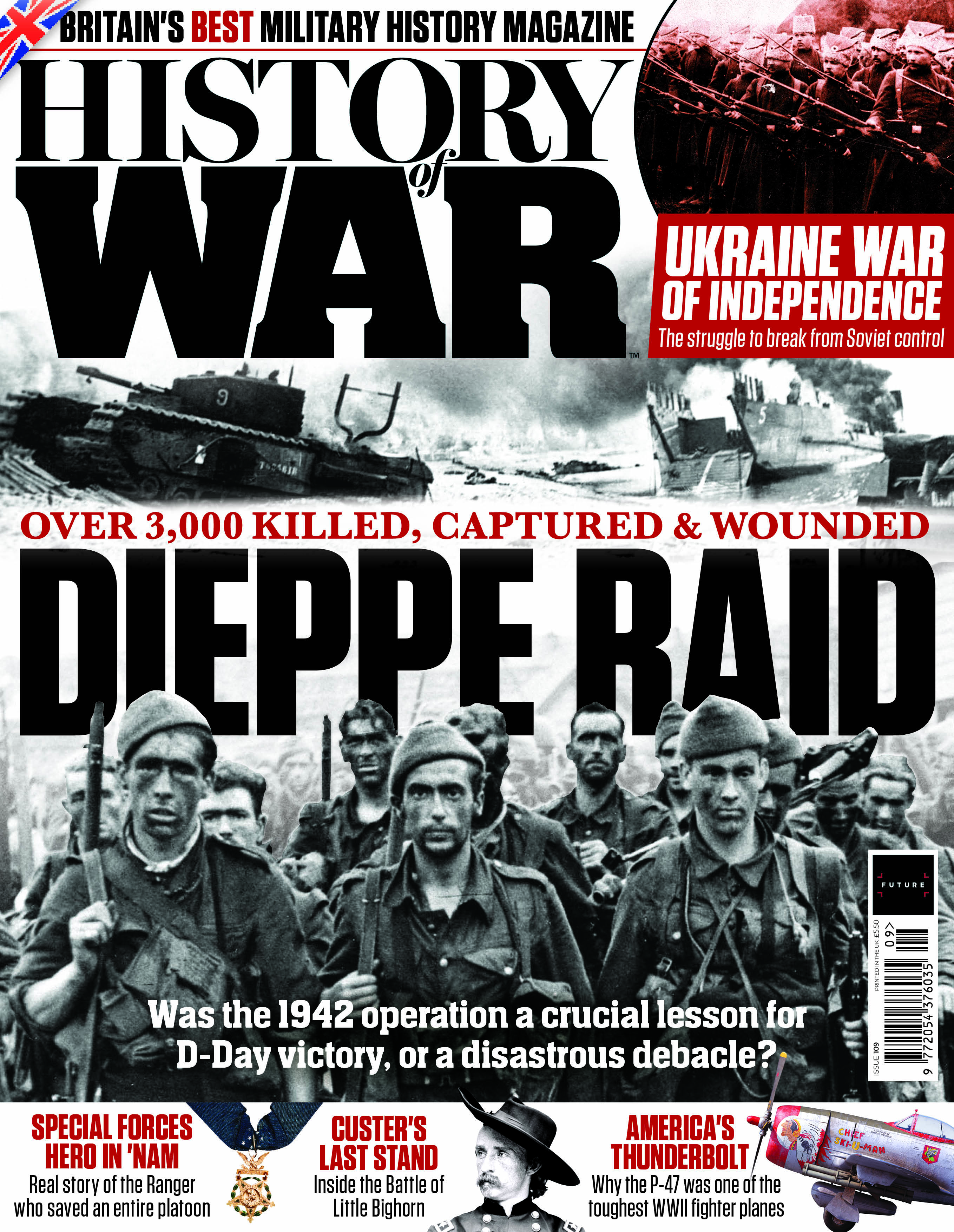

Custer's last stand: How the Native American victory unfolded

Inside History of War issue 109: Read a blow-by-blow account of the Battle of Little Bighorn.

In June, 1876, one of the most famous battles in U.S. history took place in what later became Montana and the Crow Indian Reservation. On June 25-26 a few hundred men of the 7th U.S. Cavalry, commanded by George Armstrong Custer, were outnumbered and totally defeated by a Native American coalition force of approximately 2,000 warriors, led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse.

The Native American force included warriors from the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes, according to the U.S. National Park Service. The defeat was a shock to the U.S. Army and the nation, though ultimately the tribes were forced to surrender and the nearby Black Hills, thought to be rich in gold, were seized.

Become a subscriber to get your copy of History of War magazine delivered straight to your door before it appears in stores and even save money on the usual price — starting at just $3.00 for 3 issues (followed by $28.50 per quarter).

Inside History of War issue 109, you can find a full account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, including a detailed map showing Custer's tactical errors on the field, and how the Native American forces were able to overwhelm and defeat their enemy.

Also in issue 109 historian Anthony Tucker-Jones discusses his new book "Hitler's Winter" (Osprey Publishing, 2022), which explores the German perspective of the Battle of the Bulge. He discusses what German commanders on the ground really thought of the desperate final offensive, and how the Allies were caught off-guard by the Nazi operation.

Elsewhere this issue you can take a look inside the P-47 Thunderbolt, otherwise known as the "Juggernaut", which took on the Luftwaffe in the battle for Europe's skies in WWII. This bulky but steadfast fighter plane was a favorite among pilots for its survivability and became one of the most prolific aircraft in the war.

Related: Read a free issue of History of War here

Take a look below for more on our big features in issue 109.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Custer's last stand: Blow-by-blow account

On Jun 21, 1876, Custer and his 7th Cavalry were sent to perform a wide flanking manoeuvre, and attack the Indians from the east and south, preventing them from being able to disperse into the wilderness, while other infantry and cavalry hit from the north.

On June 25, when his Crow and Arikara scouts spotted traces of the enemy encampment near the Little Bighorn River, Custer initially wanted to launch a surprise attack. However, when the scouts indicated their presence had already been spotted by enemy warriors, he decided to attack immediately. At Wolf Mountain, he split his forces into four; retaining 210 men, while sending 125 with Captain Frederick Benteen, 140 with Major Marcus Reno and 125, and the rest guarding the slow-moving pack train of supplies.

When reports of US troop movements came in mid-afternoon, the Oglala elder, named Runs the Enemy, recounted: "We could hardly believe that soldiers were so near." Soon, reports came in that US soldiers had killed an Indian boy two miles away, and a woman even closer. Oglala chief Thunder Bear says breathless women rode in saying "The country...looked as if filled with smoke, so much dust was there".

As the men assembled, Crazy Horse summoned his medicine man to invoke the spirits, adds Lehman. His battle planning and rituals took so long that one young soldier said "many of his warriors became impatient". Undeterred, Crazy Horse wove some long stems of grass into his hair and burned a pinch of medicine from the bag around his neck over a fire of buffalo chips; the smoke carrying his prayers to the heavens. After painting his face with hail stops and dusting his horse with dry earth, he was ready.

Get a full blow-by-blow account of the battle in Issue 109

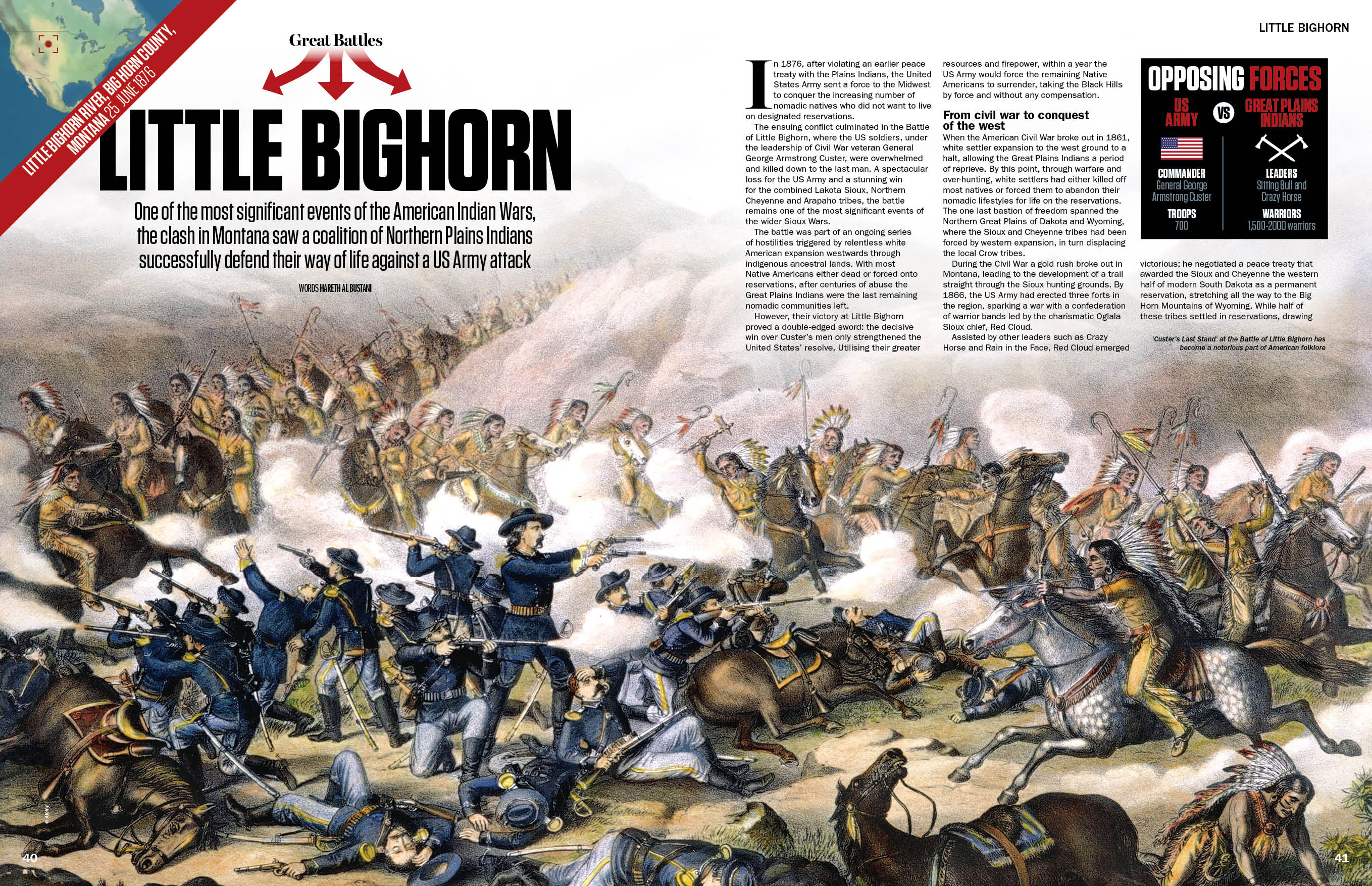

Canada's WWII tragedy at Dieppe, 80 years on

In History of War's lead feature this issue, Tim Cook of the Canadian War Museum discusses the disastrous Dieppe Raid, which saw over half of an Allied raiding force killed, captured or killed. He explains why this painful event in Canada's history has been remembered as a necessary lesson for victory on D-Day, 1944.

Two years and 14 days after the Dieppe raid — Sept. 1, 1944 — the first group of men from the 2nd Canadian Division entered the town. The lead reconnaissance unit had prepared for gunfire, but instead, they encountered crowds of cheering people thronging the streets.

"There’s was an operation planned thatwas going to bring in heavy bombers," Tim Cook told History of War magazine. "They were going to saturate bomb [Dieppe]. At the last moment… a Canadian scout goes in and sees the Germans have fled… they call off this operation. Wouldn’t that have been a bit of a different story, if the Canadians were waiting on the outskirts about to attack, guns ablaze, artillery smashing, tanks hurling shells, and with this massive carpet bombing of several hundred heavy bombers? That didn’t happen — thank goodness."

The Germans had indeed left and, two days later, on Sept. 3, the 2nd Canadian Division — having been welcomed back as liberators — held a ceremony to honour those who had come before them on August 19, 1942.

It was perhaps a bittersweet moment to pay tribute to the 765 graves, 582 of them Canadian, that lay about 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) from Dieppe — especially since so few of the raid’s veterans were present, their lives lost on the road from Caen to Falaise after the success of D-Day months earlier.

But at least in the eyes of Allied commanders, the sacrifices made during the Dieppe Raid had not been in vain. It had, in fact, according to them and the propaganda that immediately followed the operation, been a valuable lesson learned that ensured victory for the Normandy landings.

Read the full story in History of War issue 109

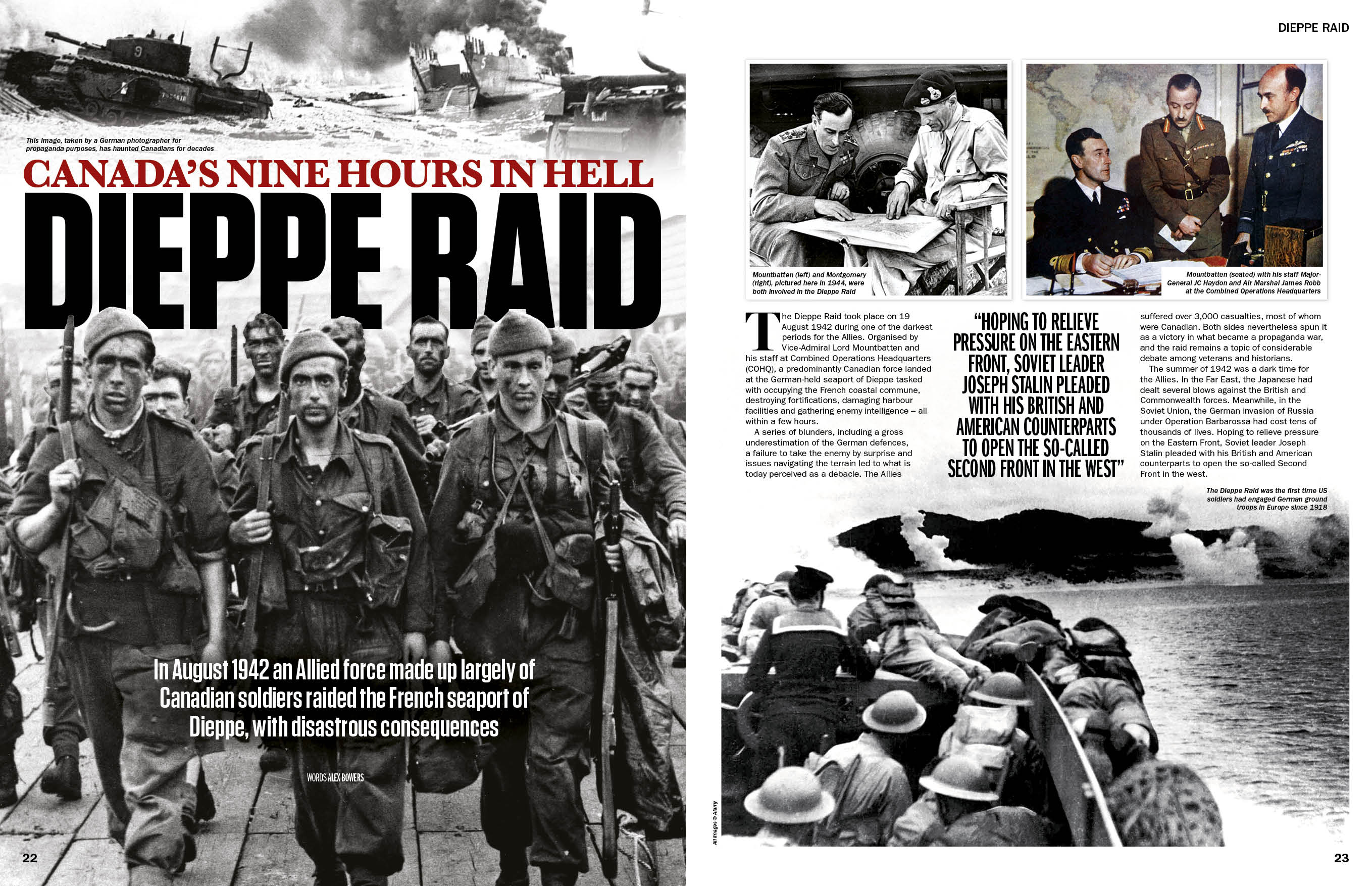

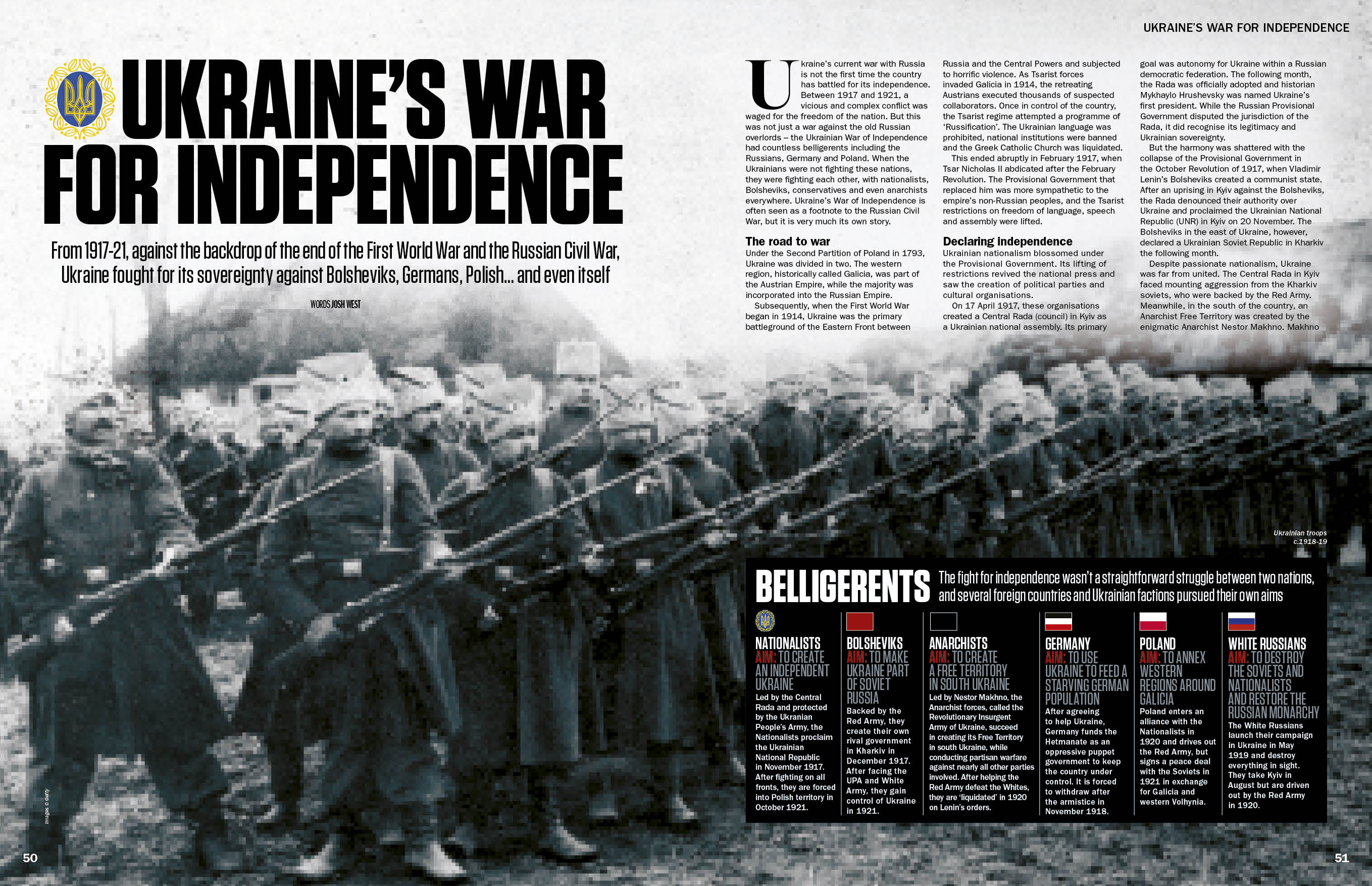

Ukraine's original war for independence

Ukraine’s current war with Russia is not the first time the country has battled for its independence. Between 1917 and 1921, a vicious and complex conflict was waged for the freedom of the nation. But this was not just a war against the old Russian overlords, the Ukrainian War of Independence had countless belligerents including the Soviets, Germany, and Poland. When the Ukrainians were not fighting these, they were fighting each other, with Nationalists, Bolsheviks, conservatives, and even Anarchists everywhere. Ukraine’s war for independence is often seen as a footnote to the Russian Civil War, but it is very much its own story.

Under the Second Partition of Poland in 1793, Ukraine was divided in two. The western region of Galacia was part of the Austrian Empire, whilst the majority was incorporated into the Russian Empire.

Subsequently, when the First World War began in 1914, Ukraine was the primary battleground of the Eastern Front between Russia and the Central Powers and subjected to horrific indecency. As Tsarist forces invaded Galacia in 1914, the retreating Austrians executed thousands of suspected collaborators. Once in control of the country, the Tsarist regime attempted a programme of ‘Russification’. The Ukrainian language was prohibited, national institutions were banned and the Greek Catholic Church was liquidated.

This ended abruptly in February 1917, when Tsar Nicholas II abdicated after the February Revolution. The Provisional Government that replaced him was more sympathetic to the empire’s non-Russian peoples. The Tsarist restrictions on freedom of language, speech, and assembly were lifted.

Pick up the latest History of War to read more

Tom Garner is the Features Editor for History of War magazine and also writes for sister publication All About History. He has a Master's degree in Medieval Studies from King's College London and has also worked in the British heritage industry for the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, as well as for English Heritage and the National Trust. He specializes in Medieval History and interviewing veterans and survivors of conflicts from the Second World War onwards.