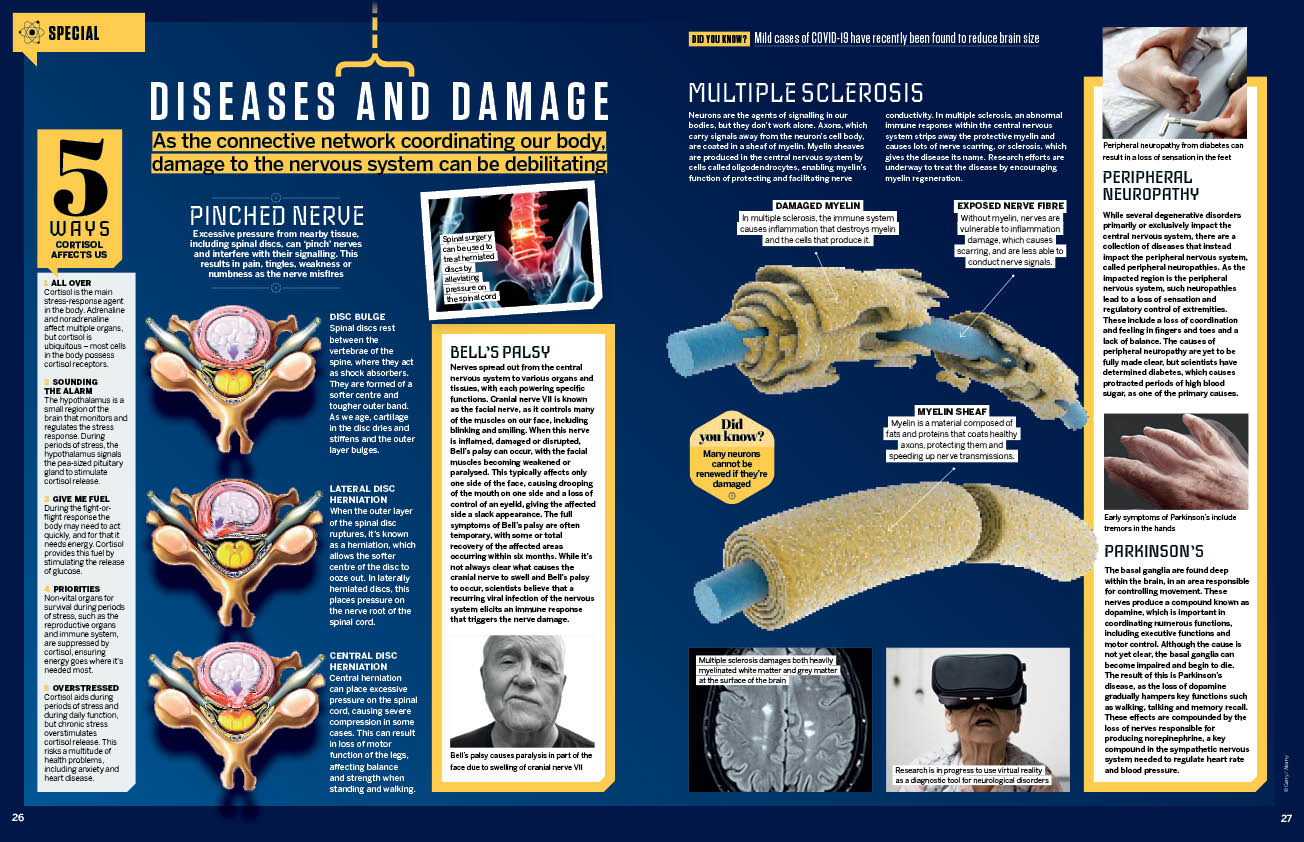

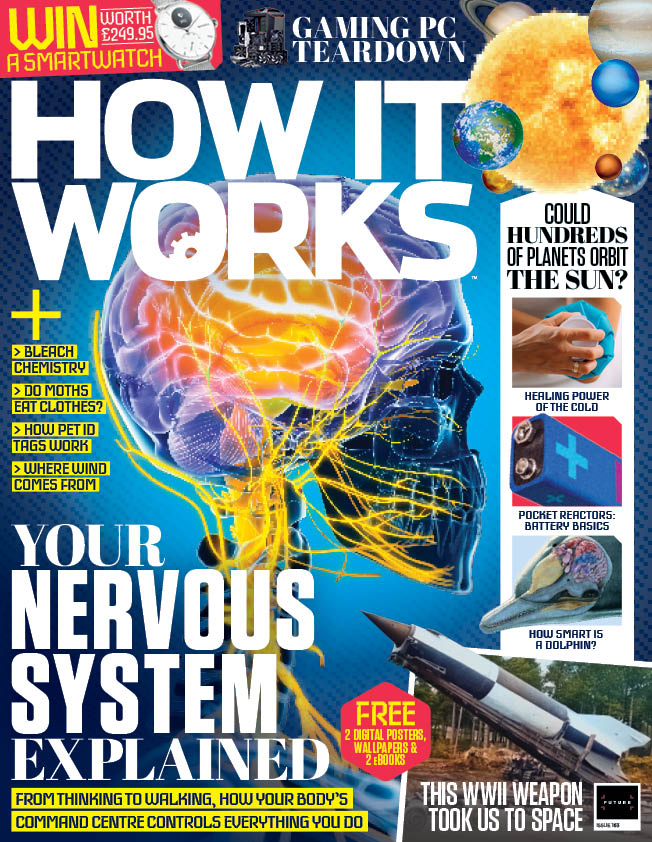

Explore you nervous system in issue 163 of How It Works magazine, the electrically charged network composed of billions of cells that co-ordinates your thoughts, feelings, and actions from head to toe.

Human beings are wonderfully complex. Relative to the numerous single-celled organisms on our planet, humans are gargantuan super structures. We boast trillions of cells that work to assemble and maintain an array of specialised tissues, organs, and bones. Together, these form a single being that walks, talks, thinks and feels.

This exceptional complexity is only made possible by a coordination center that monitors and controls the actions of our human form. We refer to this coordination center as the nervous system. Consisting of the brain, spinal cord, and reams of nerves that connect them to the rest of the body, the nervous system is a truly vast and dense network of cells. Collectively, their function is to exchange and relay information through electrical impulses, giving us the power of thought and action.

Related: Read a free issue of How It Works here

Also this issue: see how the cold can both harm and heal living tissue, take a look inside the WWII weapon that took us to space, we compare dolphin to human intelligence and what little separates these species, learn about the basics of batteries and how these pocket reactors evolved from the mighty Voltaic pile, discover the clothes moth life cycle and what's really eating holes in your cotton and cashmere, see the mind-boggling number of planets that could fit into the Solar System's habitable zone, and much more.

Read on to find out more about issue 163's biggest features.

Your nervous system explained

When we think of the nervous system, our thoughts immediately go to the brain. The brain is a hive of neuronal activity, with billions of interwoven neurons firing to preserve and recall memories, coordinate thoughts and speech, and plan future actions. Along with the spinal cord, the bone-clad parts of our nervous system are naturally called the central nervous system.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The majority of our neurons are shielded behind protective fluid and bone, where they receive signals from and dictate to organs around the body. However, the signals sent from the central nervous system must have some means of reaching their target organs. And for that they need to connect to nerves that stretch from the central nervous system all the way to the extremities of the body. This second network of nerves is called the peripheral nervous system. Together, the central and peripheral form the major divisions of the nervous system.

Exclusive offer for readers in North America: Grab yourself 4 free issues when you subscribe to How It Works, the action-packed science and technology magazine that feeds minds

The "fight or flight" sympathetic stress response evolved to help humans survive encounters with predators. For much of humanity’s hunter-gatherer existence, as we explored the wilderness, discovered new environments, and spread across the globe, we encountered all manner of dangerous fauna.

For some of these encounters, quick reaction times would have been vital, helping those with an attuned response to survive and pass on their genes to the next generation. Today most of us have little to fear from a hungry panther or a territorial grizzly bear, but the stress response is still routinely triggered, just by other means.

Now many of us encounter the same intrinsic response when we run into an angry teacher in the corridor, or when we have to present unexpectedly to our employer’s CEO at the annual meeting. While the triggers for the fight or flight response are worlds apart from our ancestors, our reactions remain the same.

Learn more about the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system in issue 163 of How It Works magazine.

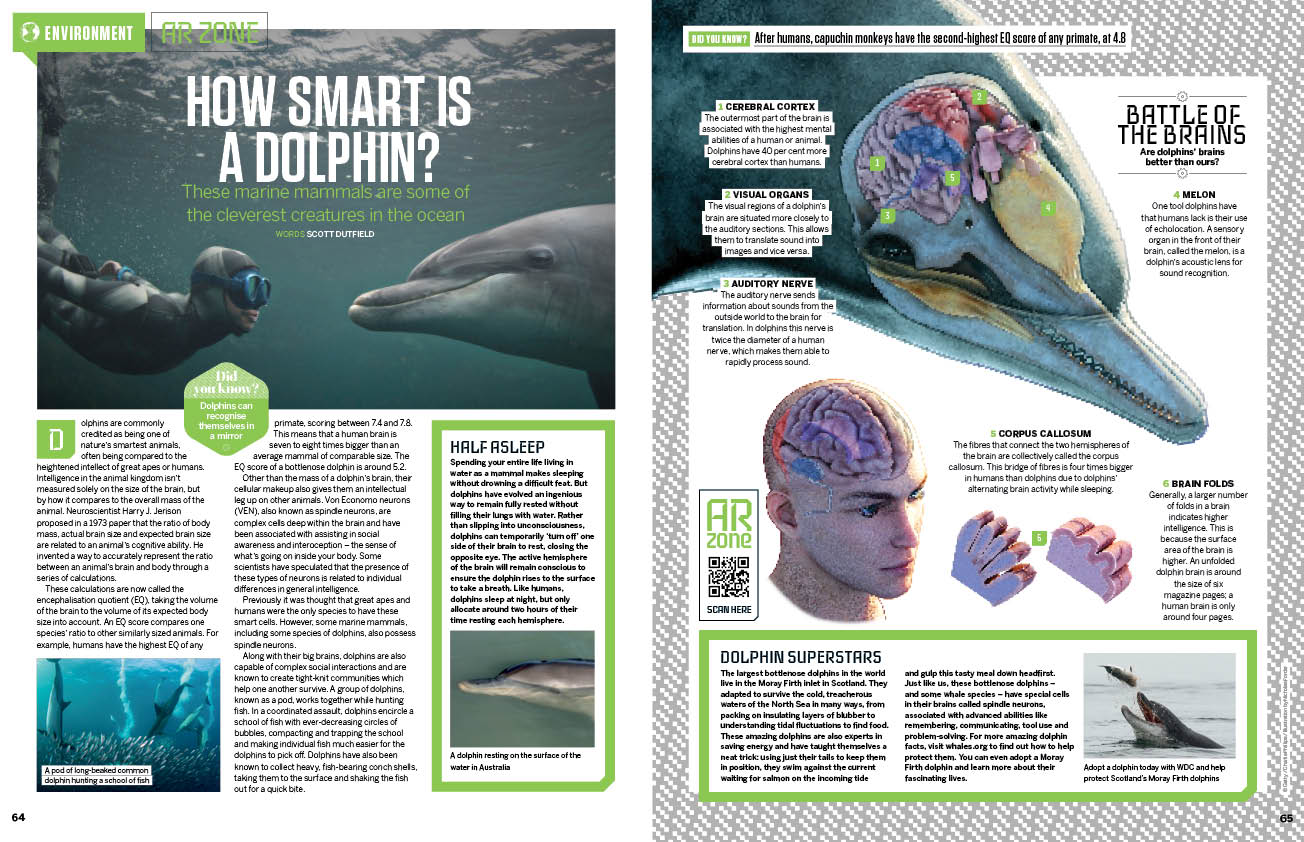

How smart is a dolphin?

Dolphins are commonly credited as being one of nature’s smartest animals, often being compared to the heightened intellect of great apes or humans. Intelligence in the animal kingdom isn’t measured solely on the size of the brain, but by how it compares to the overall mass of the animal. Neuroscientist Harry J. Jerison proposed in a 1973 paper that the ratio of body mass, actual brain size and expected brain size are related to an animal’s cognitive ability. He invented a way to accurately represent the ratio between an animal’s brain and body through a series of calculations.

Compare dolphin and human intelligence in the latest issue of How It Works magazine.

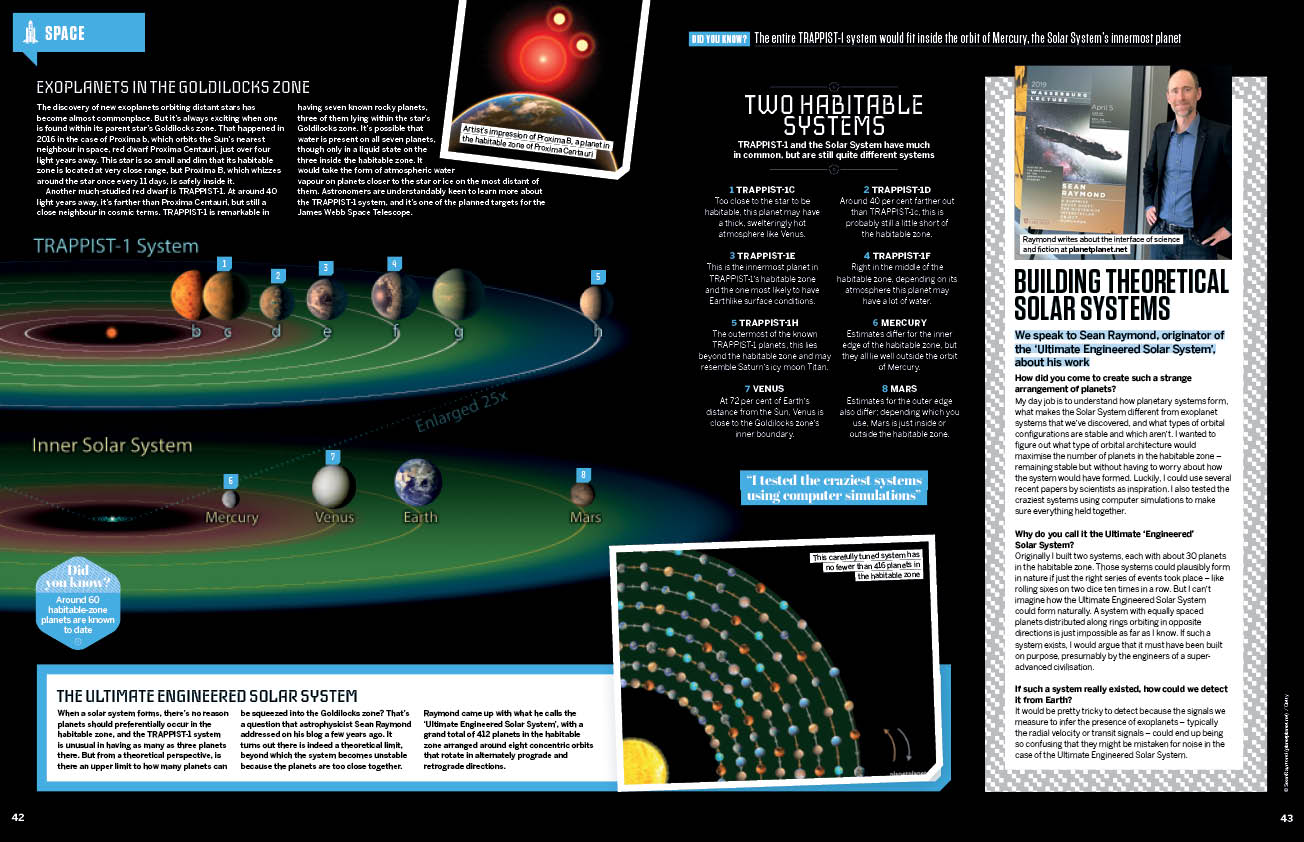

The Goldilocks Zone

In the fairy tale, Goldilocks is a fussy little girl whose porridge has to be just right, neither too hot nor too cold. It’s the same with life itself – or at least the kind of water-based life we’re familiar with on Earth. A planet has to be just right: neither so cold that water only exists as frozen ice, nor so hot that it all boils away. That’s not going to be true of all the planets orbiting a star, just those within a certain range of orbits dubbed the ‘Goldilocks zone’, or more formally the ‘habitable zone’. If a planet’s orbit takes it too close to its parent star then it will be too hot for liquid water to exist, and if it’s too far out it will be too cold. That’s obvious enough, but the actual distances involved, which define the boundaries of the habitable zone, will vary from star to star.

Our Sun is a G-type yellow dwarf, and there’s no doubt where its habitable zone lies because Earth – orbiting around 93 million miles away – is within it. But for M-type red dwarfs, which are smaller and cooler than the Sun, the habitable zone lies much closer to the star. And for a larger, hotter, A-type star like Sirius, the Goldilocks zone is further out.

For astrobiologists, the people who search for life on other planets, being in the habitable zone is just one of the factors they have to think about. Take our Moon, for example. It obviously lies in the Goldilocks zone because it’s so close to Earth, yet there’s no liquid water on its surface. That’s because atmospheric pressure and composition also have to be taken into account. This makes the Moon, which has no atmosphere to speak of, a non-starter. It’s also important not to read too much into the word ‘habitable’. Even if conditions on a planet are exactly right for the existence of liquid water, this doesn’t necessarily mean it’s inhabited. Scientists haven’t yet worked out exactly how life first arose here on Earth, so we don’t know what other subtle ingredients are necessary in addition to water and an atmosphere.

Learn more about habitable zones and see the "ultimate engineered solar system" in the latest How It Works magazine.

Ben Biggs is a keen and experienced science and technology writer, published book author, and editor of the award-winning magazine, How It Works. He has also spent many years writing and editing for technology and video games outlets, later becoming the editor of All About Space and then, Real Crime magazine.