How well do you really know your own brain?

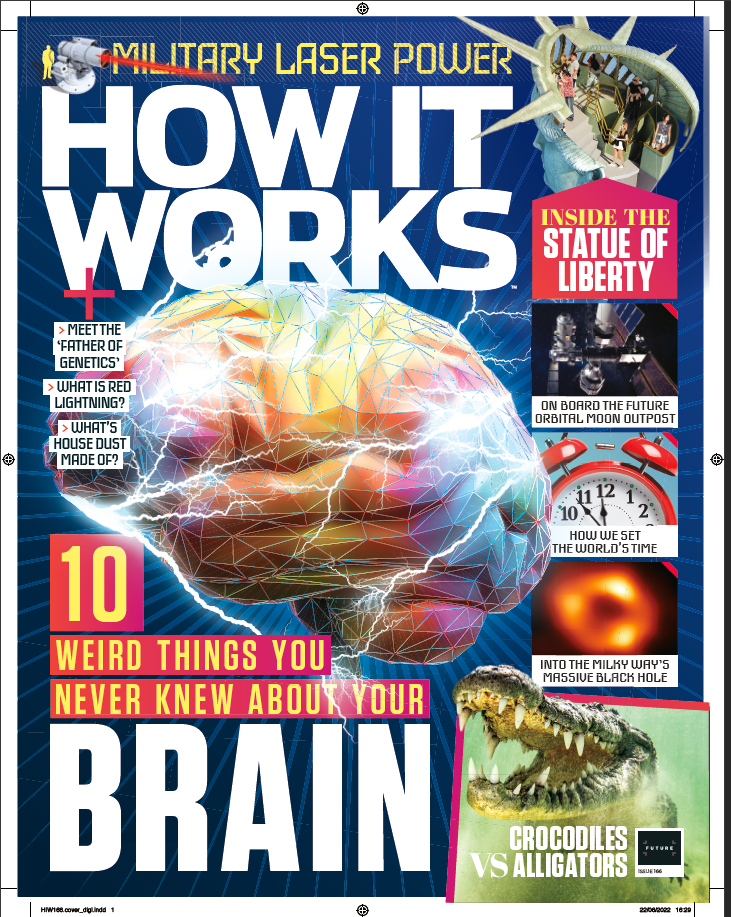

Inside How It Works 166: Discover 10 of the strangest facts about your brain.

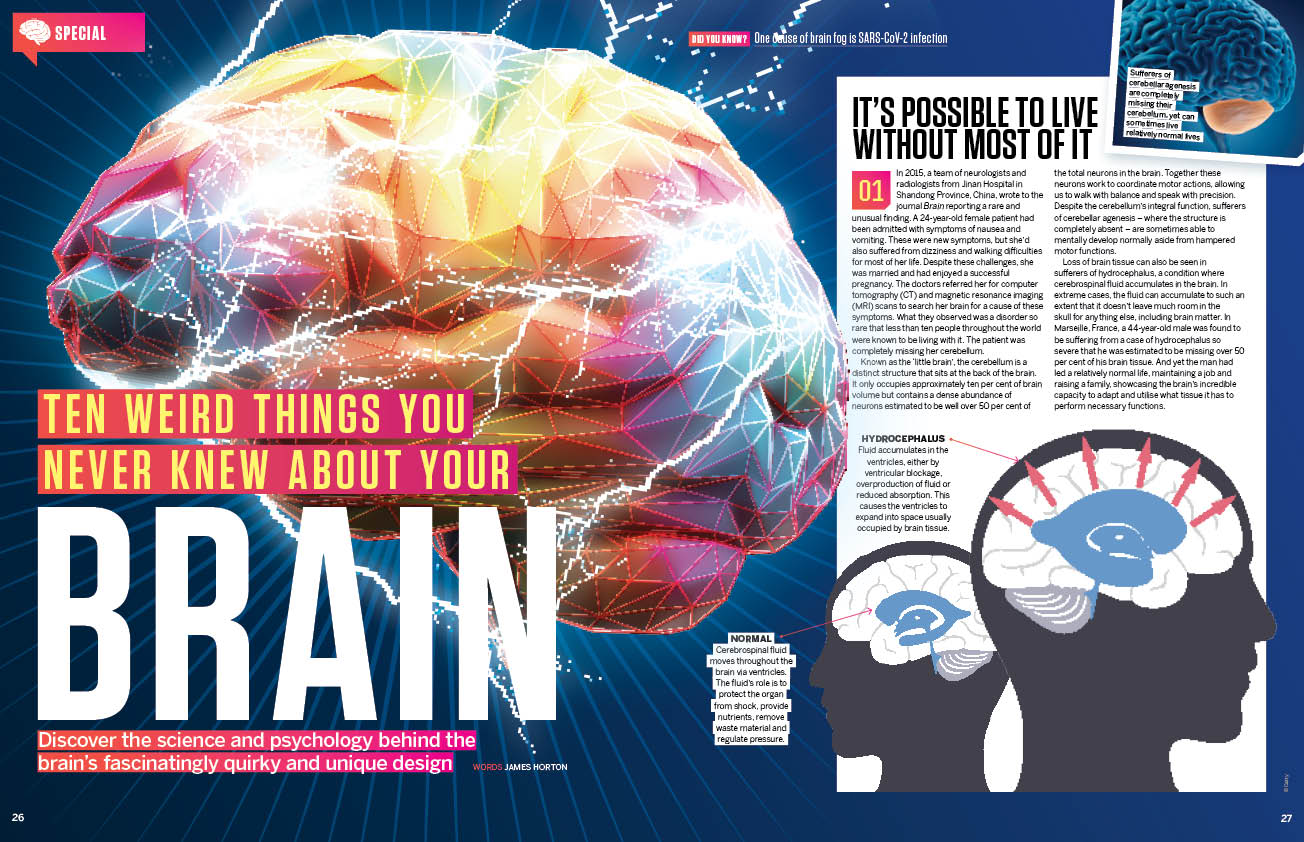

Is it possible to live without your brain? As unlikely as it may seem, scientists have discovered rare cases of patients missing large portions of their brain, yet are somehow still able to live almost normal lives. In 2015, a team of neurologists and radiologists from Jinan Hospital in Shandong Province, China, wrote to the journal Brain reporting a rare and unusual finding.

A 24-year-old female patient had been admitted with symptoms of nausea and vomiting. These were new symptoms, but she’d also suffered from dizziness and walking difficulties for most of her life. Despite these challenges, she was married and had a child.

The doctors referred her for computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to search her brain for a cause of these symptoms. What they observed was a disorder so rare that less than ten people throughout the world were known to be living with it. They discovered that the patient was completely missing her cerebellum, a region of the brain thought to be crucial for walking and other movements. Discover more about this rare condition and other incredible facts about our brain in How It Works issue 166.

Also in the latest How It Works magazine: Learn how your accent forms and how it's shaped over time; how the world keeps time with the power of atoms; see inside the Statue of Liberty and find out how it was built; what causes the strange phenomenon of red lightning; what household dust is made of (prepare to be grossed out); how Scandinavia's fjords are formed, and much more.

Read on to find out more about issue 166's biggest features.

Inside the Statue of Liberty

What household dust is made of

Weird brain facts

How the world sets the time

How fjords formed

Where your accent comes from

Inside the Statue of Liberty

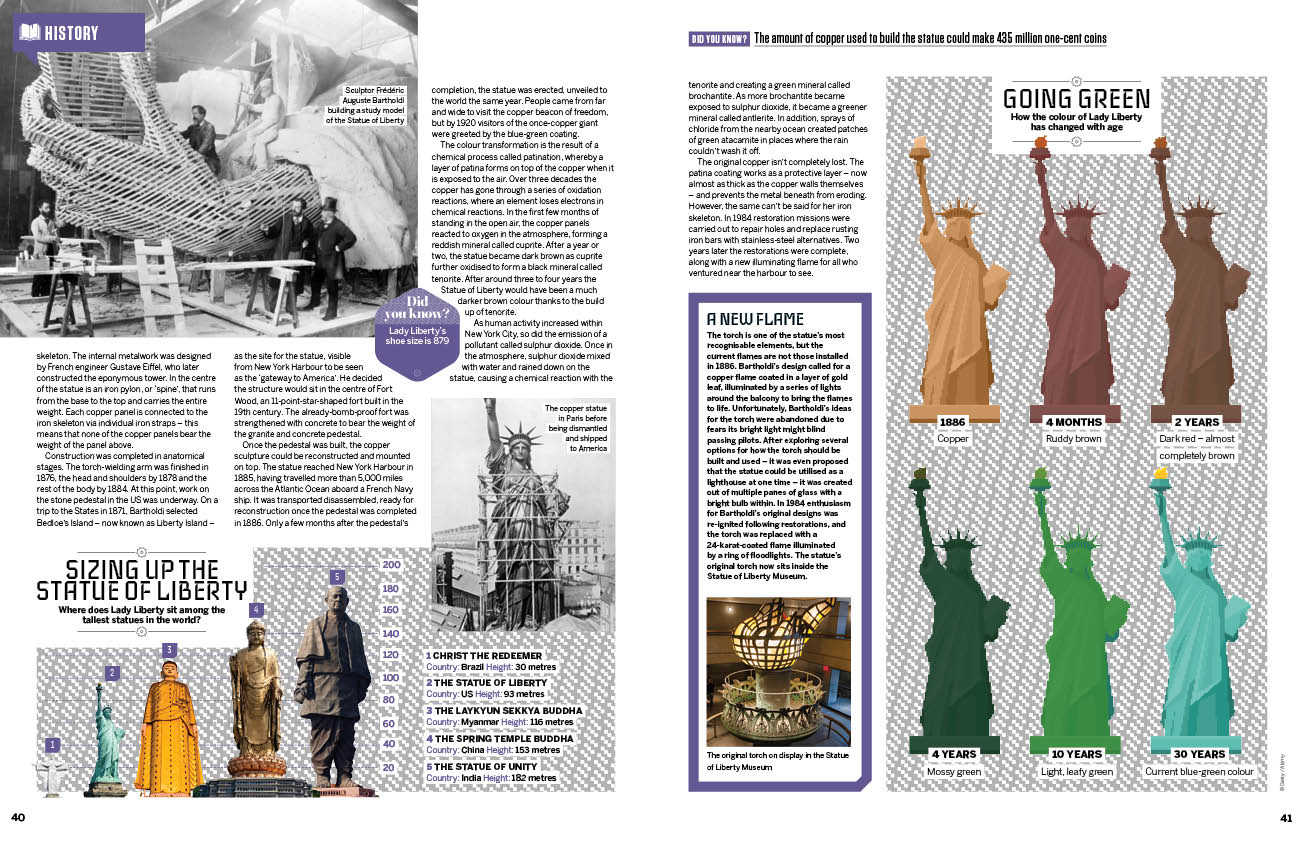

The Statue of Liberty has long been a symbol of freedom and hope. Its official title is "Liberty Enlightening the World", named by its sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. Also called Lady Liberty, the historic landmark was created to commemorate the centenary of the Declaration of Independence, along with America's close relationship with France, which gifted the statue in the late 1800s.

The initial concept came from the French poet, author and activist Édouard René de Laboulaye. It's often reported that Laboulaye came up with the idea at a dinner party in 1865 following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, but studies have found this to be false. Evidence suggests that Laboulaye conceptualized the statue between 1870 and 1871.

The statue's design also recognizes ideals laid out in the Declaration of Independence following the end of the American Civil War and the abolishment of slavery. Lady Liberty has also been described as the "Mother of Exiles" by millions of immigrants that have turned to the country for refuge.

Exclusive offer for readers in North America: Grab yourself 4 free issues when you subscribe to How It Works, the action-packed science and technology magazine that feeds minds

The copper statue — which turned from reddish brown to its iconic jade green color over time — was financed by the French public through lotteries, entertainment events and public fees, whereas the stone pedestal on which it stands was funded by the U.S. through theatrical events, auctions and a lucrative opportunity for donors to have their names printed in "The New York World" newspaper by the renowned Joseph Pulitzer.

Learn more about how the Statue of Liberty was built in issue 166 of How It Works magazine.

How does the world keep time?

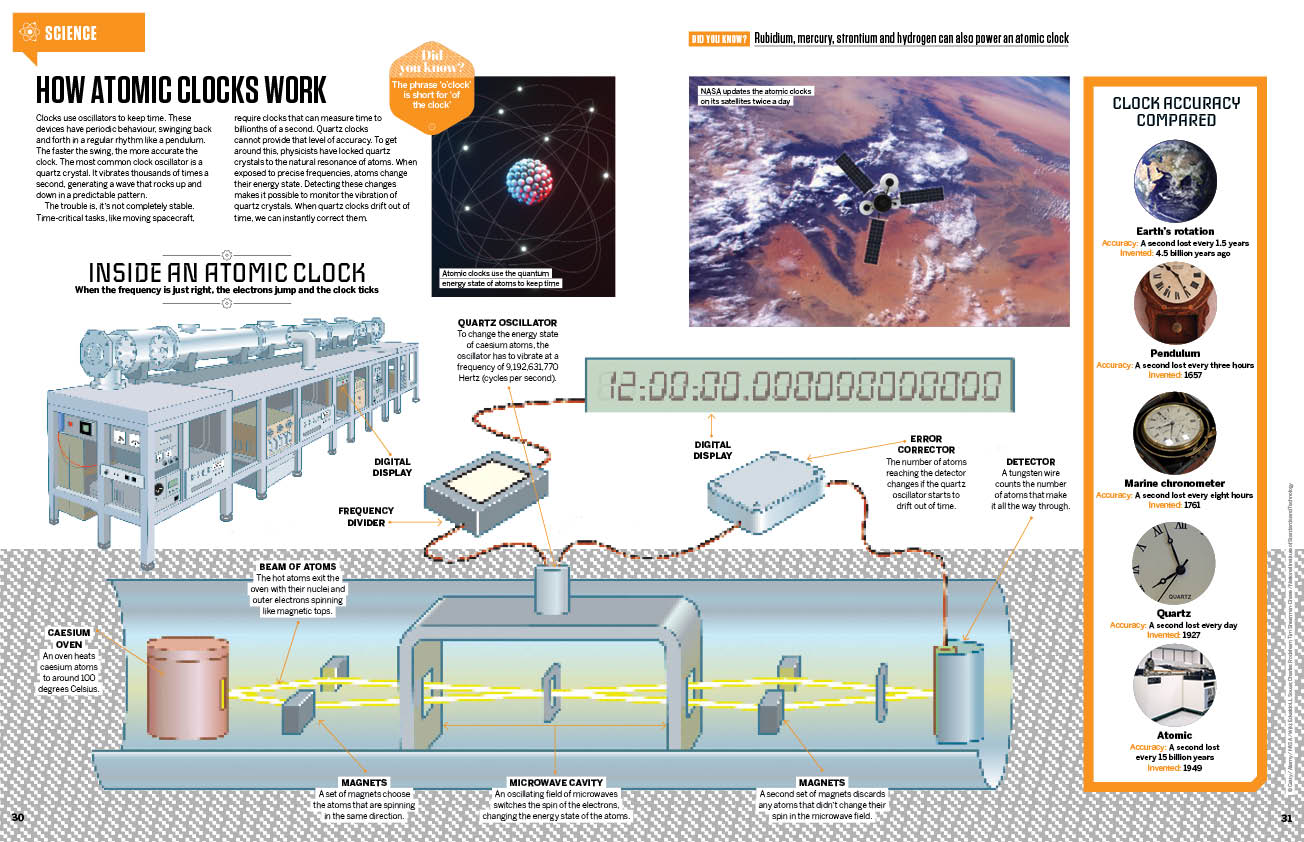

Have you ever wondered how the whole world stays in sync? We live in different time zones, but from New York to Melbourne, a second is always a second. That's because everyone sets their local clocks using an internationally agreed standard called Coordinated Universal Time, also known as UTC.

UTC is defined by an agency of the United Nations called the International Telecommunication Union. It's based on two measurements: the ticking of hundreds of ultra-stable atomic clocks (International Atomic Time) and the rotation of the Earth (Universal Time).

Nations across the world set their local time by adding or subtracting from UTC depending on their position on the globe. UTC, or the world clock, has been around since the first day of the 1960s, shortly after Louis Essen built the first atomic clock. This precision timepiece promised to solve the centuries-old problem of second hands running too fast or too slow.

Before the 1950s, the most accurate clocks used vibrating quartz crystals to keep time, but the seconds would drift on a daily basis. Essen’s invention used the quantum properties of caesium atoms to keep the crystals in sync.

Now more than 400 extremely stable atomic clocks keep track of time the world over. Each one transmits a signal to the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in France. The bureau compares them once a month to come up with a final number called International Atomic Time. Each clock gets a different weighting in the calculation depending on how stable it is.

See how an atomic clock keeps such precise time in the latest issue of How It Works magazine.

How fjords formed

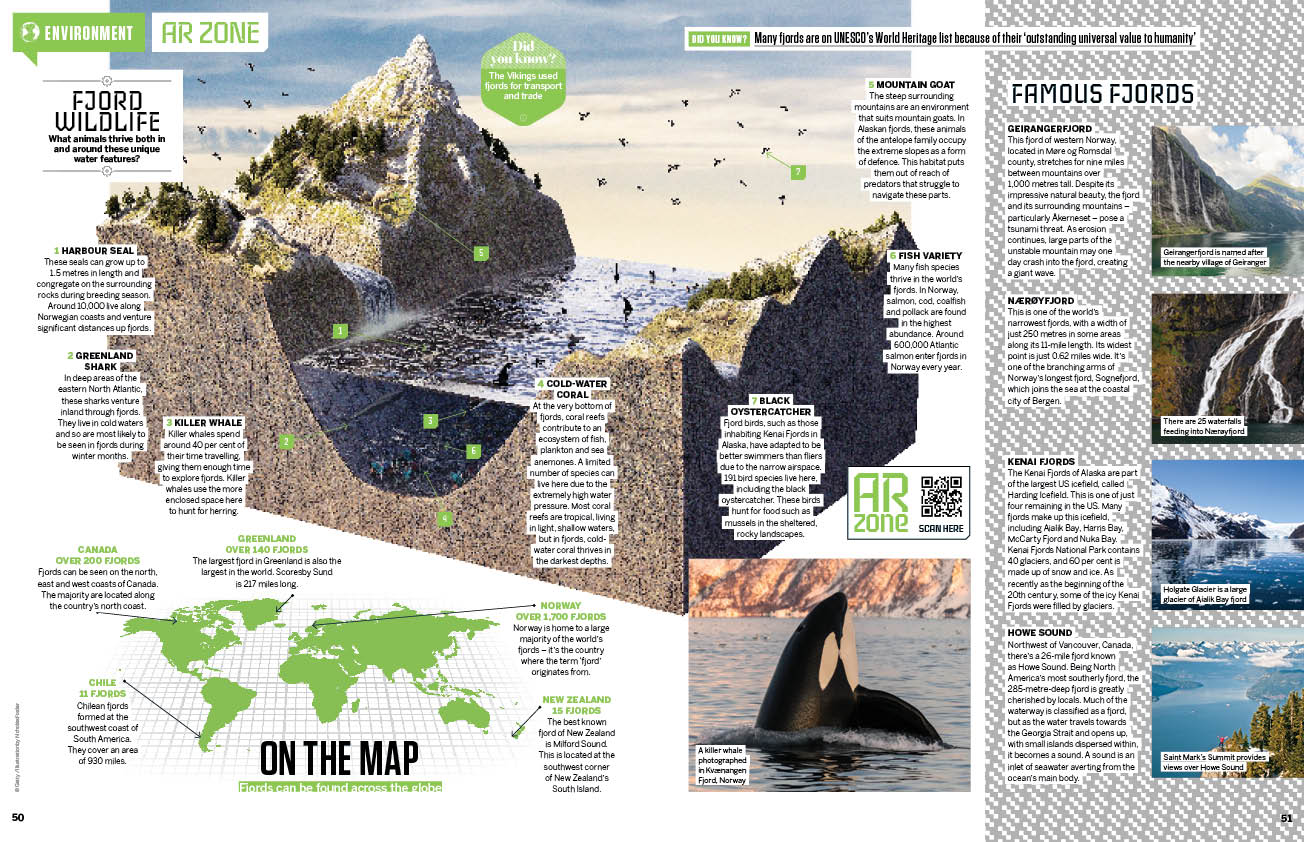

Walled in by steep, rocky cliffs, river-like systems track through some of the planet's most mountainous terrain. The water found flowing here is a combination of freshwater that has run down from the mountaintops and saltwater filling in from the sea. The water traverses mountain valleys like a river, but this is a more unique system known as a fjord.

Relatively rare across the world, fjords are defined by their formation. Their convenient low paths were produced by glaciers as they eroded the land during the last ice age. The movement of glaciers was strongest inland, resulting in the deepest sections of these narrow waterways — sometimes thousands of metres deep — being located farthest from the coast.

Fjords follow a pre-carved path, directing water between dramatic mountain peaks. Throughout history, humans have utilised fjords for inland navigation. The term fjord is derived from this, meaning "where one fares through" in Norwegian. Norway and other Scandinavian countries hold the highest percentage of Earth’s fjords, but this name has been adopted internationally.

Fjords can branch out into many arms, spreading far across the landscape. Many of these stretch into very remote areas, and due to many fjords being difficult to access, they remain largely unpolluted. They also serve as a record of Earth's natural history and a protected environment where the movement of glaciers from many thousands of years ago can be tracked.

Discover how fjords form and see inside one of these ancient waterways in the latest How It Works magazine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ben Biggs is a keen and experienced science and technology writer, published book author, and editor of the award-winning magazine, How It Works. He has also spent many years writing and editing for technology and video games outlets, later becoming the editor of All About Space and then, Real Crime magazine.