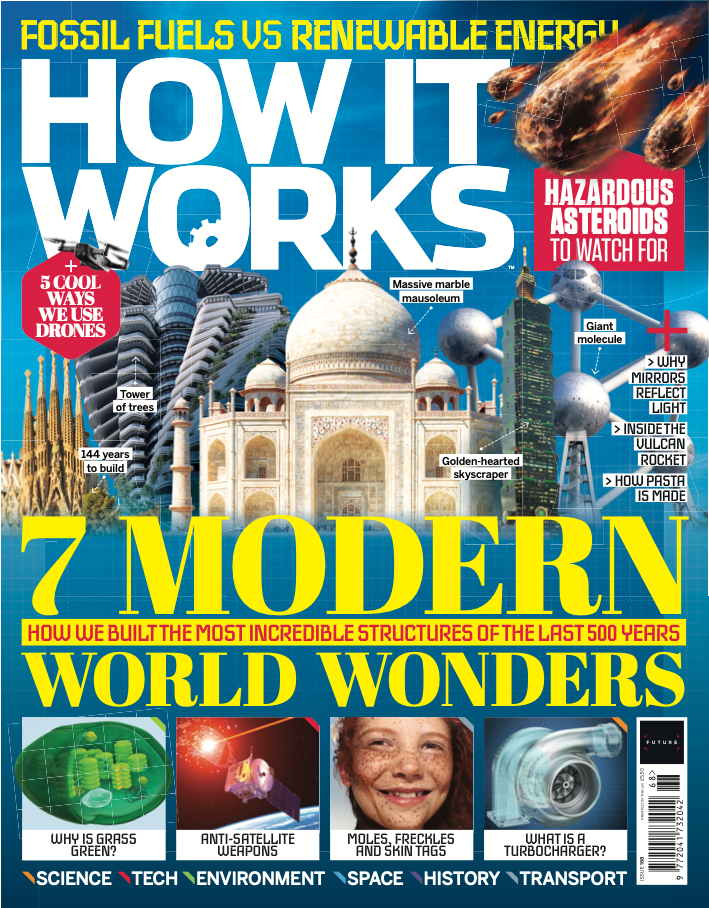

Discover 7 wonders of the modern world in issue 168 of How It Works magazine, and take a tour of some of the planet’s most awe-inspiring construction marvels, from staggeringly tall skyscrapers, to structures that break new ground in form and function.

Related: Read a free issue of How It Works here

Also this issue, you can discover how the the first modern computer — Charles Babbage's Difference Engine — worked to perform complex calculations yet was completely overlooked at the time. Discover the pros and cons of fossil fuels versus alternative energy.

See which large asteroids pose a hazard to Earth in the near future and how NASA plans to divert one of them with its DART mission. Learn how pasta is mass-produced in factories, why the grass is green, how gastropods form shells, five ways drones have changed our world, and much more.

Read on to find out more about issue 168's biggest features.

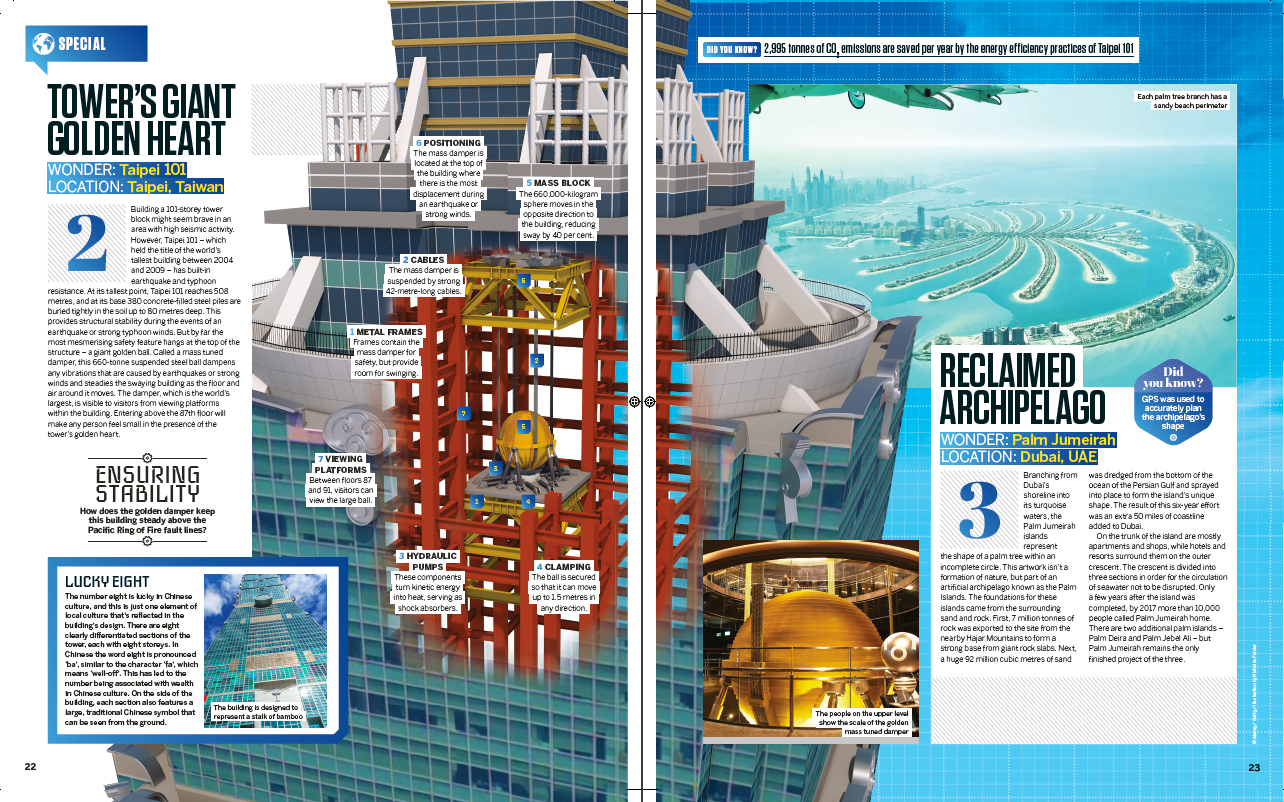

7 Modern Wonders

On March 19, 1882, Spanish architect Francisco de Paula del Villar launched the building of La Sagrada Familia basilica. His part in the project would be over when he resigned from the job just one year later following an argument with another architect on the team, but the basilica’s evolution is still continuing to this day, meaning this modern wonder has been a work in progress for over 140 years.

Exclusive offer for readers in North America: Grab yourself 4 free issues when you subscribe to How It Works, the action-packed science and technology magazine that feeds minds

La Sagrada Familia is due to be completed in 2026, meaning that it will have taken longer to build than the Egyptian pyramids. The original purpose of the building was to encourage Christianity in Barcelona at a time when the religion was in decline there.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When Antoni Gaudi took over as chief architect in 1883, a new style was proposed. Gaudi’s signature style included geometric patterns and biomimicry — shapes largely inspired by nature. These elements can be seen in fine detail throughout La Sagrada Familia, such as the branching columns creating a forest-like theme in the central church area.

Learn more about La Sagrada Familia and other world wonders in issue 168 of How It Works magazine.

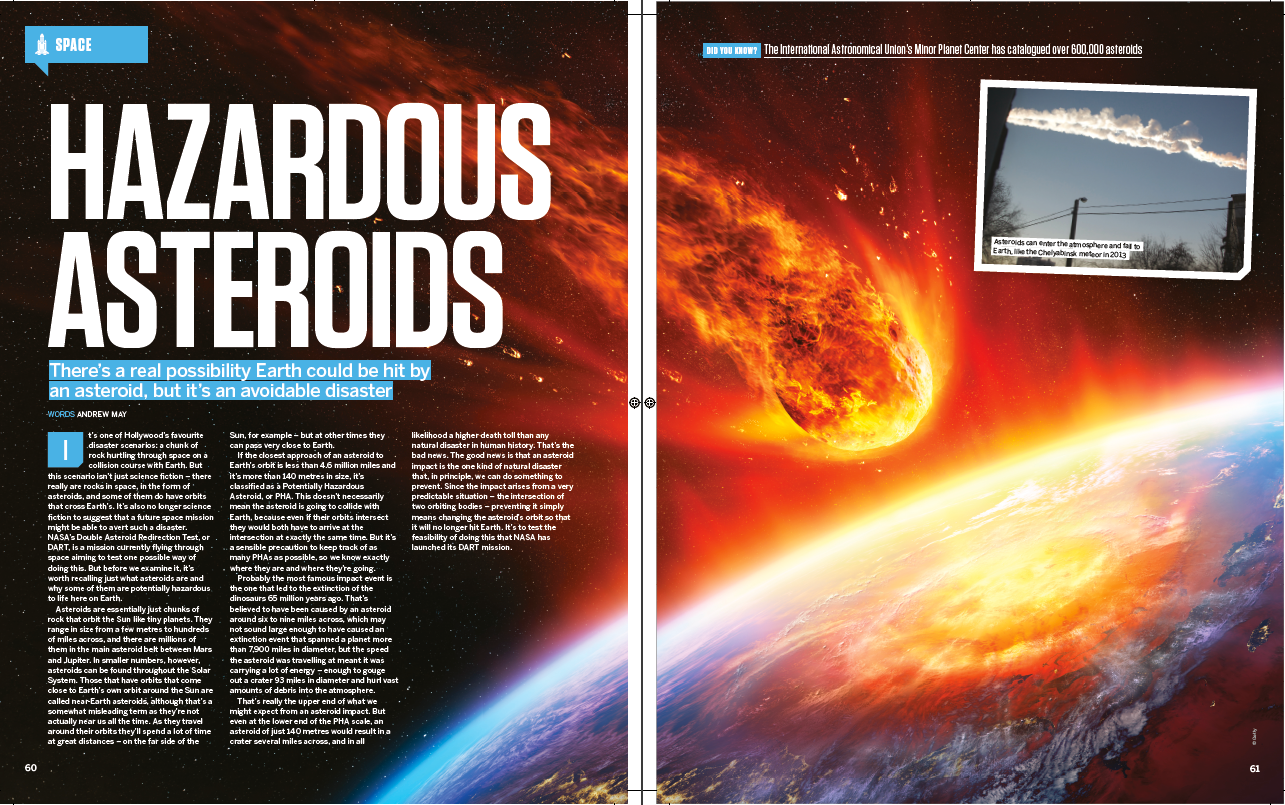

Hazardous asteroids

How It Works spoke with planetary scientist Nancy Chabot from Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) about NASA's upcoming mission to divert an asteroid in space.

What will the DART mission tell us about the viability of asteroid deflection?

One of the major challenges is targeting a small asteroid in space at very high speed when that asteroid has never been imaged by spacecraft previously. It is only within the last hour of the spacecraft’s approach to Dimorphos that the onboard camera can distinguish it from Didymos, the larger asteroid that Dimorphos orbits.

The DART team at APL developed the SMART Nav [Small-body Maneuvering Autonomous Real Time Navigation] algorithms that autonomously navigate it to impact Dimorphos. Demonstrating this capability in space at high speed is challenging, but it’s also an important technology demonstration for planetary defence. DART’s demonstration of this technology will be a major result to inform future planetary defence activities.

Assuming the impact is successful, why is there uncertainty over how much the orbit will change?

How the asteroid reacts to the kinetic impact of the DART spacecraft is one of the main objectives to be investigated. We know from other asteroids that have been explored that they have a range of shapes, internal structures, surface properties and strengths, and these characteristics will influence how much the asteroid Dimorphos is deflected in its orbit around Didymos.

Read the rest of the interview and learn more about the DART mission in the latest issue of How It Works magazine.

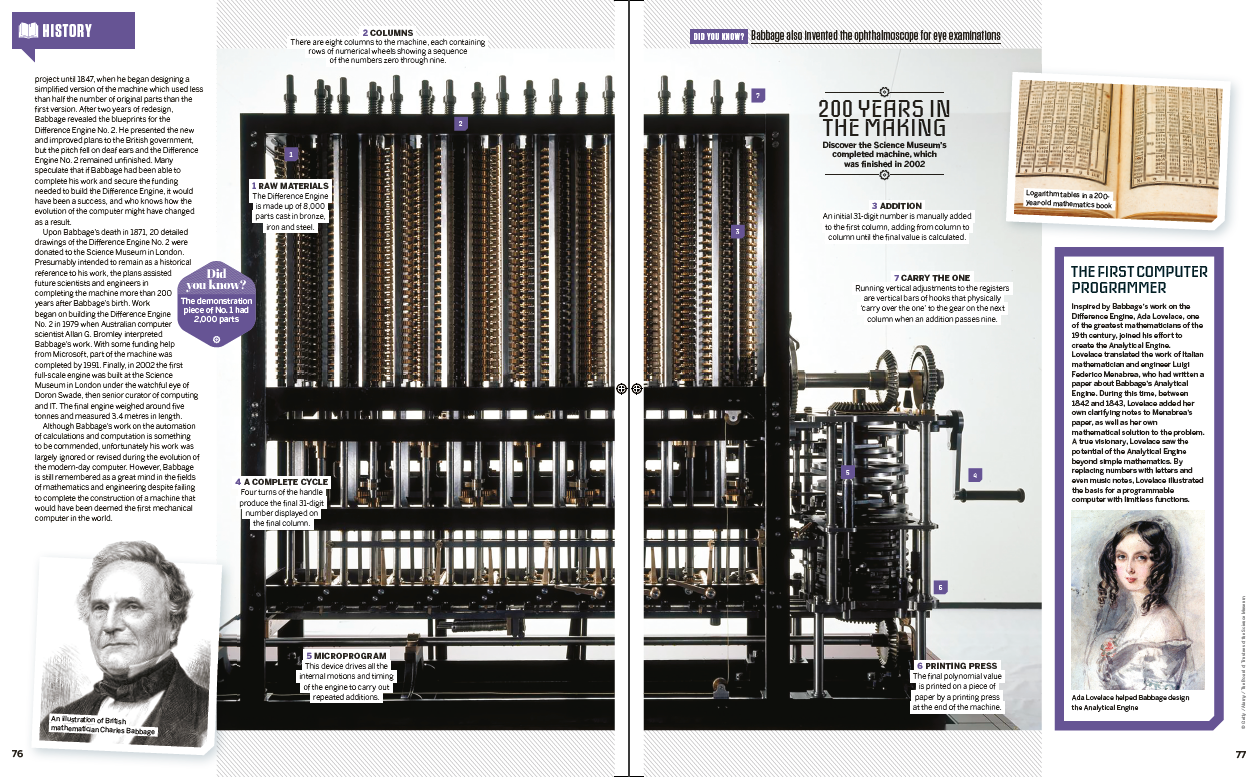

Inside the first computer

The history of the modern-day computer is a 200-year journey of technological evolution contributed to by countless inventors and scientists from across the world. One of the pioneering minds on the computer’s timeline was Charles Babbage, an English mathematician that designed several machines to automatically complete complex calculations.

In the early 1800s, Babbage was tasked by the British Admiralty with producing an accurate table of logarithms — printed tables used to perform bigger calculations commonly used in navigation — as a former professor of Cambridge University.

Having trawled through many existing printed tables, Babbage became disgruntled by the number of comparative errors between them. To remove the chance of human error from creeping its way into these tables, Babbage set out to mechanise the process of creating them.

The first iteration of Babbage’s mechanical solution was called the Difference Engine No. 1, the design of which called for a giant hand-cranked machine that used interlocking gears and large numerical columns to make calculations. With need of an investor to finance his project, the mathematician turned to the British government for support.

Babbage’s financial request was granted, and he enlisted the help of engineer Joseph Clement to carry out the machine’s construction. In Babbage’s designs, a fully realized Difference Engine consisted of 25,000 parts to complete its calculations. The machine was designed in two parts: the first was the calculating machine and the second was a printing press to document the calculation.

But in 1842, after 20 years of development and thousands of pounds spent to create only a small demonstrative portion of the machine, known as the "beautiful fragment", Babbage’s funding was withdrawn following a parliamentary vote.

See inside the Difference Machine and learn how it became a major influence on the modern day computer in How It Works magazine.

Ben Biggs is a keen and experienced science and technology writer, published book author, and editor of the award-winning magazine, How It Works. He has also spent many years writing and editing for technology and video games outlets, later becoming the editor of All About Space and then, Real Crime magazine.