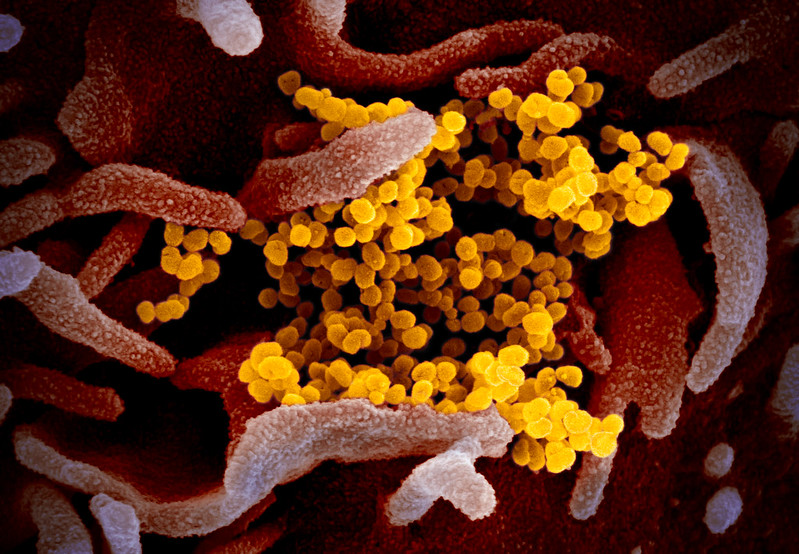

Here’s how long the coronavirus will last on surfaces, and how to disinfect those surfaces.

"Never mix household bleach with ammonia or any other cleanser," CDC says.

Editor's Note: This story was updated on Wednesday (March 18) to include a warning not to mix bleach with household cleaning products and to include an update on the publication of the findings. This story was updated on Tuesday (March 24) to note that viral particle RNA was found up to 17 days after passengers disembarked the Diamond Princess cruise ship, but experts don't know if they are viable or not.

As the coronavirus outbreak continues to accelerate in the U.S., cleaning supplies are disappearing off the shelves and people are worried about every subway rail, kitchen counter and toilet seat they touch.

But how long can the new coronavirus linger on surfaces, anyway? The short answer is, we don't know. A new analysis found that the virus can remain viable in the air for up to 3 hours, on copper for up to 4 hours, on cardboard up to 24 hours and on plastic and stainless steel up to 72 hours. This study was originally published in the preprint database medRxiv on March 11, and now a revised version was published March 17 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

What's more, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was found on "a variety of surfaces" in cabins of both symptomatic and asymptomatic people who were infected with COVID-19 on the Diamond Princess cruise ship, up to 17 days after the passengers disembarked, according to a new analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, this was before disinfection procedures took place and "data cannot be used to determine whether transmission occurred from contaminated surfaces," according to the analysis. In other words, it's not clear if the viral particles on these surfaces could have infected people.

Another study published in February in The Journal of Hospital Infection analyzed several dozen previously published papers on human coronaviruses (other than the new coronavirus) to get a better idea of how long they can survive outside of the body.

They concluded that if this new coronavirus resembles other human coronaviruses, such as its "cousins" that cause SARS and MERS, it can stay on surfaces — such as metal, glass or plastic — for as long as nine days (In comparison, flu viruses can last on surfaces for only about 48 hours.)

But some of them don't remain active for as long at temperatures higher than 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius). The authors also found that these coronaviruses can be effectively wiped away by household disinfectants.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For example, disinfectants with 62-71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide or 0.1% sodium hypochlorite (bleach) can "efficiently" inactivate coronaviruses within a minute, according to the study. "We expect a similar effect against the 2019-nCoV," the researchers wrote, referring to the new coronavirus. But even though the new coronavirus is a similar strain to the SARS coronavirus, it's not clear if it will behave the same.

Diluted household bleach solutions, alcohol solutions containing at least 70% alcohol and most EPA-registered common household disinfectants should be effective at disinfecting surfaces against the coronavirus, according to the CDC. The bleach solution can be prepared by mixing 5 tablespoons (one-third cup) of bleach per gallon of water or 4 teaspoons of bleach per quart of water, the CDC wrote in a set of recommendations.

Please be mindful and use caution when cleaning! #RVCfire #Safety pic.twitter.com/jUPOxmNaR9March 17, 2020

However, "never mix household bleach with ammonia or any other cleanser," the CDC said. Mixing common cleaners together can create toxic fumes, according to a previous Live Science report. For example, when bleach is mixed with an acidic solution, a chemical reaction produces chlorine gas, which can cause irritation of the eyes, throat and nose. At high concentrations, that gas can cause breathing difficulties and fluid in the lungs, and at very high concentrations it can lead to death, according to the report.

It's possible that a person can be infected with the virus by touching a contaminated surface or object, "then touching their own mouth, nose, or possibly their eyes," according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "But this is not thought to be the main way the virus spreads." Though the virus remains viable in the air, the new study can't say whether people can become infected by breathing it in from the air, according to the Associated Press.

The virus is most likely to spread from person to person through close contact and respiratory droplets from coughs and sneezes that can land on a nearby person's mouth or nose, according to the CDC.

If a person in a household is suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19, "clean and disinfect high-touch surfaces daily in household common areas," according to the CDC's recommendations. Common household areas include tables, hard-backed chairs, doorknobs, light switches, remotes, handles, desks, toilets and sinks.

What's more, "As much as possible, an ill person should stay in a specific room and away from other people in their home," they wrote. The caregiver should try to stay away from the ill person as much as possible; this means the ill person, if possible, should clean and disinfect surfaces themselves. If that's not possible, the caregiver should wait "as long as practical" after an ill person uses the bathroom to clean and disinfect surfaces, according to the CDC.

- The 9 deadliest viruses on Earth

- 27 devastating infectious diseases

- 11 surprising facts about the respiratory system

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.