What Is the Hubble Constant?

Reference Article: Facts about the Hubble constant.

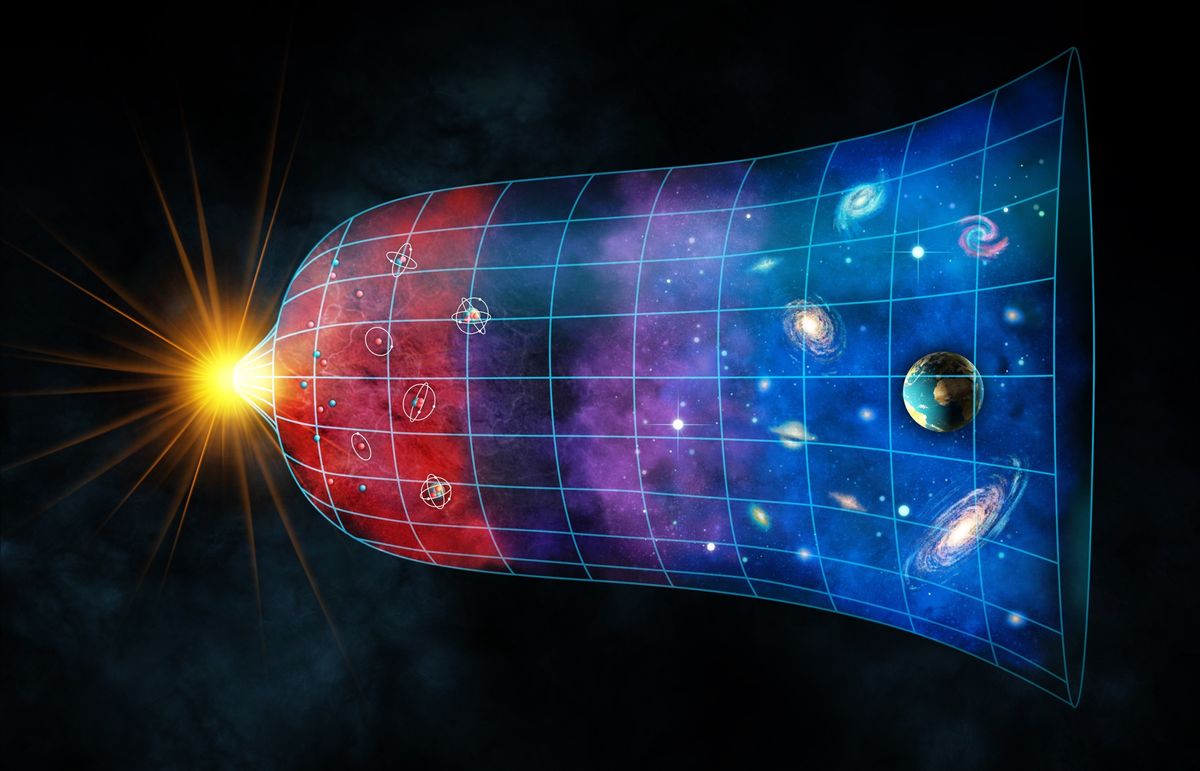

The Hubble constant is a unit that describes how fast the universe is expanding at different distances from a particular point in space. It is one of the keystones in our understanding of the universe's evolution — and researchers are mired in a debate over its true value.

How the Hubble constant was discovered

The Hubble constant was first calculated in the 1920s, by American astronomer Edwin Hubble. He discovered that fuzzy, cloud-like celestial objects were distant galaxies sitting outside our own Milky Way galaxy, according to NASA.

Earlier, American astronomer Henrietta Leavitt showed that special stars called Cepheid variables, whose luminosity regularly rises and falls, had a tight correlation between the period of their variation and their intrinsic brightness. By knowing how bright a Cepheid truly is and how dim its light appeared when seen from Earth, Hubble was able to derive the Cepheid's distance.

What Hubble found was remarkable. All of the galaxies in the universe appeared to be moving away from our planet. Furthermore, the farther a galaxy was, the faster it was receding. This observation, which Hubble made in 1929, became the basis for what's known as Hubble's law, which states that there is a relationship between the distance an object in the cosmos is from us and the speed at which it is receding, according to an explainer from Cornell University.

The Earth is not, by the way, in some privileged spot at the center of the universe. Any observer at any place in the cosmos will see that heavenly entities are moving away at a rate that increases with distance.

Using his data, Hubble attempted to estimate the constant that bears his name, coming up with a value of around 342,000 mph per million light years, or 501 kilometers per second per megaparsec (Mpc) in cosmologists' units. (A megaparsec is equal to 3.26 million light-years.) More accurate modern techniques have refined this initial measurement and shown that it was around 10 times too high.

Why the Hubble constant keeps changing

But exactly how much Hubble was off by remains a matter of contention. In the 1990s, astronomers discovered that distant supernovas were dimmer, and therefore farther away, than they had previously suspected. This finding indicated that the universe was not only expanding but also accelerating in its expansion. The result necessitated the addition of dark energy — a mysterious force pushing everything in the cosmos apart — into cosmologists' models of the universe.

After this surprise, researchers tried to pin down the rate of cosmic acceleration, to figure out how the universe began and evolved, and what its ultimate fate will be. Data from Cepheid variables and other astrophysical sources calculated the Hubble constant to be 50,400 mph per million light-years (73.4 km/s/Mpc) in 2016.

But an alternate number has been derived using information from the European Space Agency's Planck satellite. The spacecraft has spent the past 10 years making measurements of the cosmic microwave background — an echo from the Big Bang that contains data about the universe's basic parameters. Planck found the Hubble constant to be 46,200 mph per million light-years (67.4 km/s/Mpc) in 2018.

The two values might not seem very different. But each is extraordinarily precise, and they contain no overlap between their error bars. If the Cepheid estimate is wrong, it means all of astronomers' distance measurements have been incorrect since the days of Hubble. If the second estimate is wrong, then new and exotic physics would have to be introduced into physicists' models of the universe. So far, neither team of scientists who determined the numbers has been willing to admit any major measurement mistakes.

In July 2019, astronomers used a novel technique to come up with a new calculation of the Hubble constant. Researchers studied the light of red giant stars, which all reach the same peak brightness at the end of their lives. This means that, as with the Cepheids, astronomers can look at how dim red giant stars appear from Earth and estimate their distance. The new value sat right in between the two old ones — 47,300 mph per million light-years (69.8 km/s/Mpc) — yet scientists haven't declared victory quite yet.

"We wanted to make a tiebreaker," Barry Madore, an astronomer at the University of Chicago and a member of the team that made the latest measurement, told Live Science. "But it didn't say this side or that side is right. It said there was a lot more slop than everybody thought before."

The debate continues. Some have suggested that the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), which looks at ripples in the fabric of space-time made by distant neutron stars crashing into one another, might provide another independent data point. Others are looking to gravitational lensing, which occurs when extremely massive objects bend and warp space-time like a magnifying glass, providing a peek at entities even farther away, to clear up the discrepancy. But at the moment, no one is quite sure where and when the final answer about the Hubble constant will appear.

Additional resources:

- Watch "Hubble's Contentious Constant" from NASA Science.

- Read more about the latest Hubble constant determination, from NASA.

- Find out more about why the Hubble constant isn't constant, from Deep Astronomy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.