10 controversies that 'broke' science in 2023

Get the popcorn ready as we wrap up this year's most hotly debated science stories.

There are stories you expect to ruffle some feathers — we're looking at you, aliens — and then there are the ones we never thought would kick up a storm. This year, scientists surprised us with claims of successful room temperature superconductivity, reported sightings of long-extinct species and alternative theories to the origin of humankind. We've not missed out on juicy UFO content either, so without further ado, here's our pick of the most controversial science stories in 2023.

UFO and 'alien mummy' Congress hearings

In May, Congress held its first public hearing on UFOs since the 1960s to discuss 144 reported sightings of mysterious objects. During the hearings, two military officials were questioned about their knowledge of the unexplained phenomena. The May hearing was followed by another in July, in which three military witnesses claimed evidence of non-human technologies was being hidden from the public. All three witnesses said it's possible unidentified anomalous phenomena (UAP) are being launched by aliens interested in America's nuclear capabilities, testing for weaknesses in U.S. air defense systems or conducting reconnaissance in American airspace.

Related: 20 of the best conspiracy theories

Mexico had its own extraterrestrial matters to deal with, after a journalist unveiled two "alien" bodies before the country's congress in September. Together with a military medical doctor, the journalist, Jaime Maussan, claimed that DNA tests showed the bodies were non-human but not necessarily extraterrestrial. Scientists rallied to refute these claims and debunk them.

'Anomalous' metal spheres

This year, a prominent Harvard astrophysicist claimed that more than 50 "anomalous" metal spheres pulled from the Pacific Ocean could be the work of intelligent aliens. Avi Loeb claimed the tiny pellets likely fell into the ocean in 2014, when a fireball shot across the sky above Papua New Guinea. Loeb argued the blazing object could be a relic from another star system and might harbor traces of alien technology.

In November, several studies found that the metal spheres are more likely a by-product of burning coal and therefore probably come from industrial pollution on Earth. Loeb refuted these results in a blog post on Nov. 15. He argued that coal is non-magnetic and could not have been picked up by the instruments he used to dredge the pellets from the ocean. He noted that 93% of the collected samples have not yet been analyzed and cautioned that scientists should not jump to conclusions.

Tasmanian tigers prowling the wilderness

Based on reported sightings since 1910, researchers suggested in March that Tasmanian tigers (Thylacinus cynocephalus) survived in the wild until the 1980s and may still be prowling the Tasmanian wilderness today. These marsupials were thought to have gone extinct in 1936, when the last known Tasmanian tiger died in captivity, but the researchers estimated the earliest date for extinction was in the mid-1950s — that is, if the species did go extinct.

However, the study was met with skepticism, as the findings were based solely on reported sightings of Tasmanian tigers. No carcass was ever found to suggest the species persisted in the wild, experts told Live Science, and the resemblance between Tasmanian tigers and dogs means people who reported sightings could easily have been mistaken.

Contentious Brazilian dinosaur fossils

In May, paleontologists criticized a team of researchers in Europe after they published a study on 115 million-year-old dinosaur fossils that had been unearthed by commercial diggers in Brazil then sold and shipped to Germany. The specimens belong to a carnivorous species related to Spinosaurus known as Irritator challengeri, which the new study suggests scooped up prey like a pelican.

The study authors thought the fossils legally belonged to Germany, as they arrived there before 1990, after which time Brazil began restricting scientific exports to other countries. But an older 1942 law states that Brazilian fossils are federal property and cannot be sold, meaning the fossils may have been stolen. Paleontologists, including the authors, agreed the fossils should be returned to Brazil.

Semiconductor furore

This summer, researchers in South Korea claimed they made a superconductor at room temperatures and pressures, sparking a flurry of attempts to replicate the results. If verifiable, the discovery of a material able to carry electricity in everyday temperatures and without electrical resistance would open new technological windows.

But other experts cautioned the published work was sloppy and not peer-reviewed. When they tried to replicate the findings, none of the materials they created yielded identical results to LK-99, the South Korean team's superconductor. Subsequent publicized attempts have also proven unsuccessful. Regardless of the outcome for LK-99, the announcement gave rise to meaningful discussions on social media and elsewhere about an area of science unfamiliar to the general public.

Hominin fossils in space

In September, a Virgin Galactic space flight took off from Earth with priceless and extremely contentious cargo: the fragmentary remains of two of our ancient relatives, Australopithecus sediba and Homo naledi. South African-born billionaire Timothy Nash carried the hominin fossils to the edge of space in a cigar-shaped tube, causing an uproar in the scientific community.

Related: NASA may have unknowingly found and killed alien life on Mars 50 years ago, scientist claims

The permit to take the fossils on the flight, which was approved by the South African Heritage Resources Agency, said the goal of the mission was to promote science and bring global recognition to human origins research in South Africa. But experts criticized the undertaking because it lacked a scientific purpose, especially as a malfunction could have destroyed the fossils. Critics also noted the trip raised ethical issues surrounding the respect for human ancestral remains and tainted the image of paleoanthropological research.

Antarctica's ozone hole

A study that claimed the ozone hole above Antarctica is not recovering as fast as we thought and could be getting bigger came under fire in November, with experts criticizing the methodology and accusing the authors of cherry-picking data.

The conclusion that the concentration of ozone at the center of Antarctica's ozone hole decreased by 26% between 2001 and 2022 omitted several factors — including three consecutive years of La Niña from 2020 to 2022, massive wildfires that raged in Australia during 2020 and water vapor from Tonga's huge eruption in 2022 — that would explain why the past few years have been unusual, experts told Live Science. Experts also questioned the authors' decision to exclude two years' worth of data, which they argued would have skewed the results.

Overall, experts said, the results were unrealistic and useless to infer much about global ozone recovery trends.

Alternative origin story

A newly identified ape fossil from an 8.7 million-year-old site in Turkey led scientists to posit that hominines — a group that includes humans, the African apes and their fossil ancestors (and different from hominins, which comprise species belonging to the human lineage after it diverged from the ancestors of chimpanzees and bonobos) — first evolved in Europe. This deviates from the conventional view that hominines originated exclusively in Africa and suggests members of this group dispersed to Africa from the Mediterranean instead.

But paleontologists pointed out that comprehensive analyses of great ape and early human relative fossils do not support this argument. It's also possible that the newfound species, Anadoluvius turkae, migrated to the Mediterranean from Africa after evolving there, rather than the other way round, experts told Live Science. Fossils like these are sparse in the African fossil record, and while that doesn't mean hominines weren't there, it does raise questions about where the group first evolved, they added.

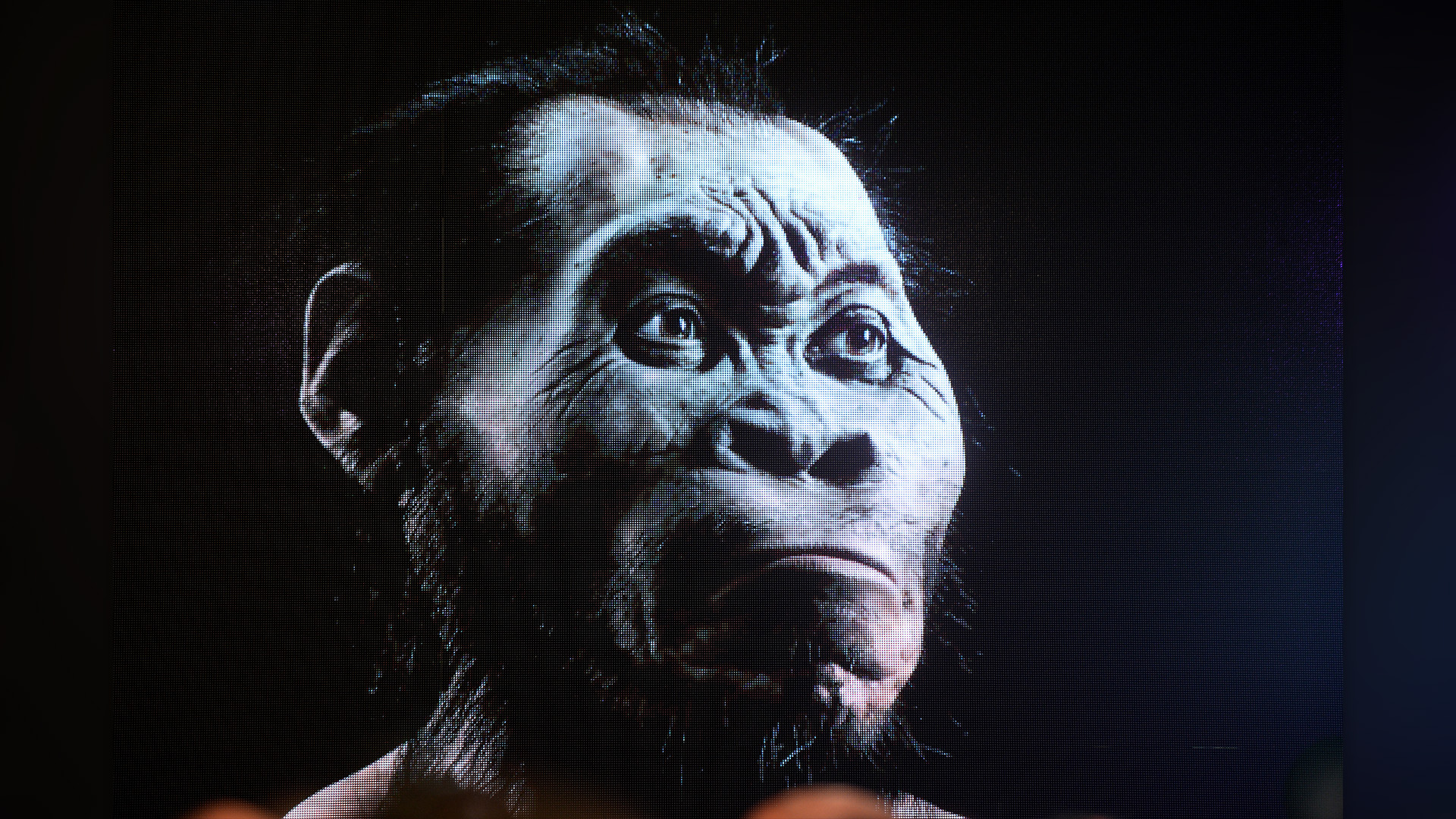

Netflix documentary under scrutiny

Homo naledi — an ancient human relative that lived about 300,000 years ago — became a lightning rod for controversy earlier this year after a research team claimed the extinct hominins deliberately buried their dead and engraved rocks. These complex behaviors, for which there was "no convincing scientific evidence," were featured in the hit Netflix documentary "Unknown: Cave of Bones" (2023), which was released just days after the claims were published in the journal eLife.

Related: Early human relatives purposefully crafted stones into spheres 1.4 million years ago, study claims

The findings could be substantiated one day, experts told Live Science, but there is currently no strong evidence to support the idea that hominins with orange-size brains could perform behaviors only known in species with much larger brains, such as modern humans. The team behind the claims responded to reviewers' comments, but it's unlikely their words will be the last in this debate.

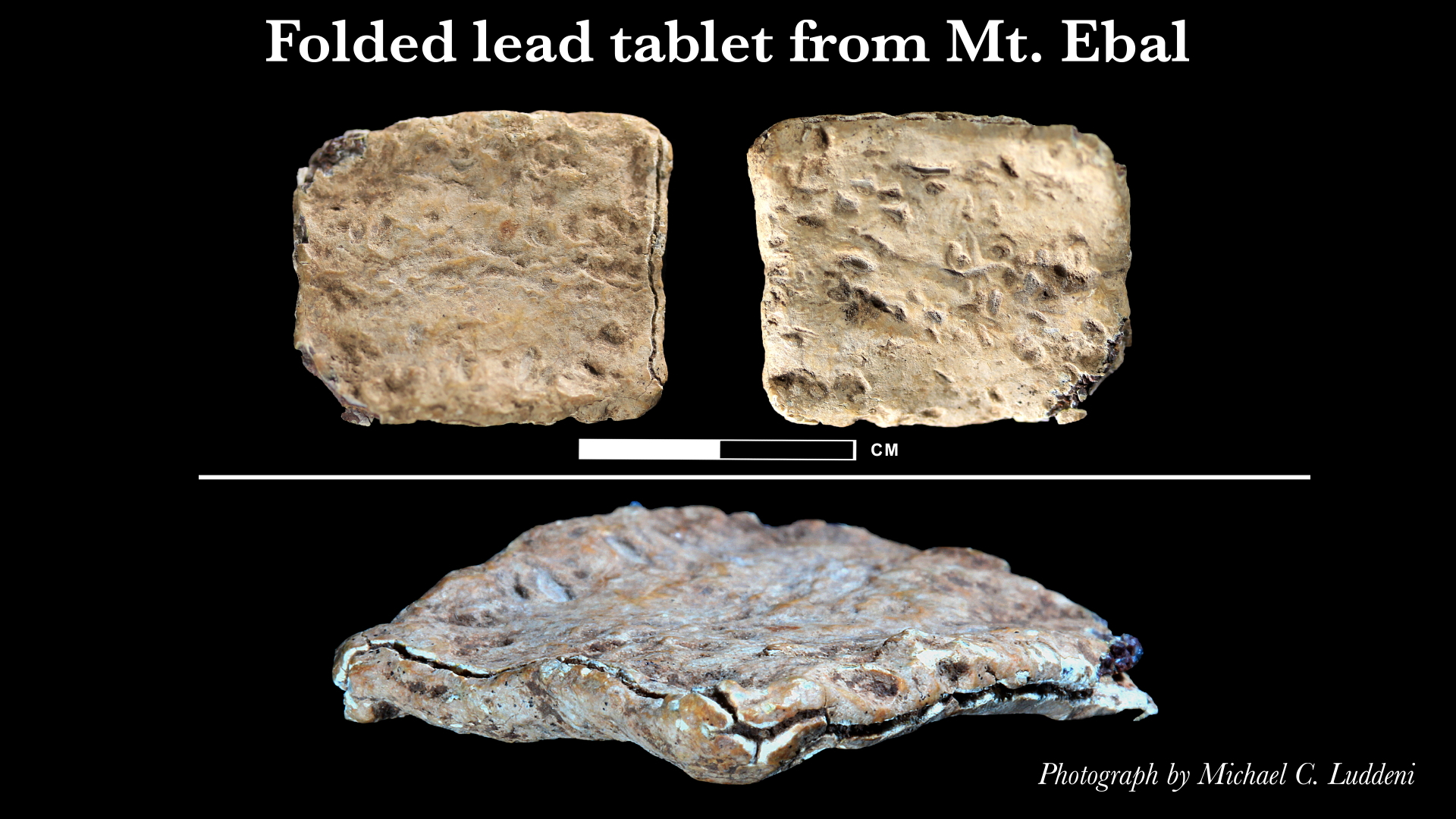

'Curse tablet' or fishing weight?

A postage stamp-size piece of lead was discovered in the West Bank in 2019, and this year, some researchers found that it carried the earliest-known inscription of the name of the Israelite god Yahweh. The authors of the original paper called the artifact a "curse tablet," based on their interpretation of the markings as calling on Yahweh to curse his enemies. But others are not convinced, because they think it shows no words and might actually be a fishing weight.

The controversial lead tablet bore no inscriptions on the inside, critics told Live Science, just indentations caused by weathering. The tablet closely resembles weights commonly used for fishing or birding nets during the time the tablet was dated to, between 1400 and 1200 B.C.

The original researchers responded to critics by saying they are confident there is writing on the tablet and are working on a second paper detailing inscriptions on the folded tablet's exterior.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.