10 mind-blowing black hole discoveries from 2024

From missing links, to primordial beginnings, to extremely powerful plasma jets that could be shaping our universe in mysterious ways, here are the top 10 black hole discoveries that blew our minds this year.

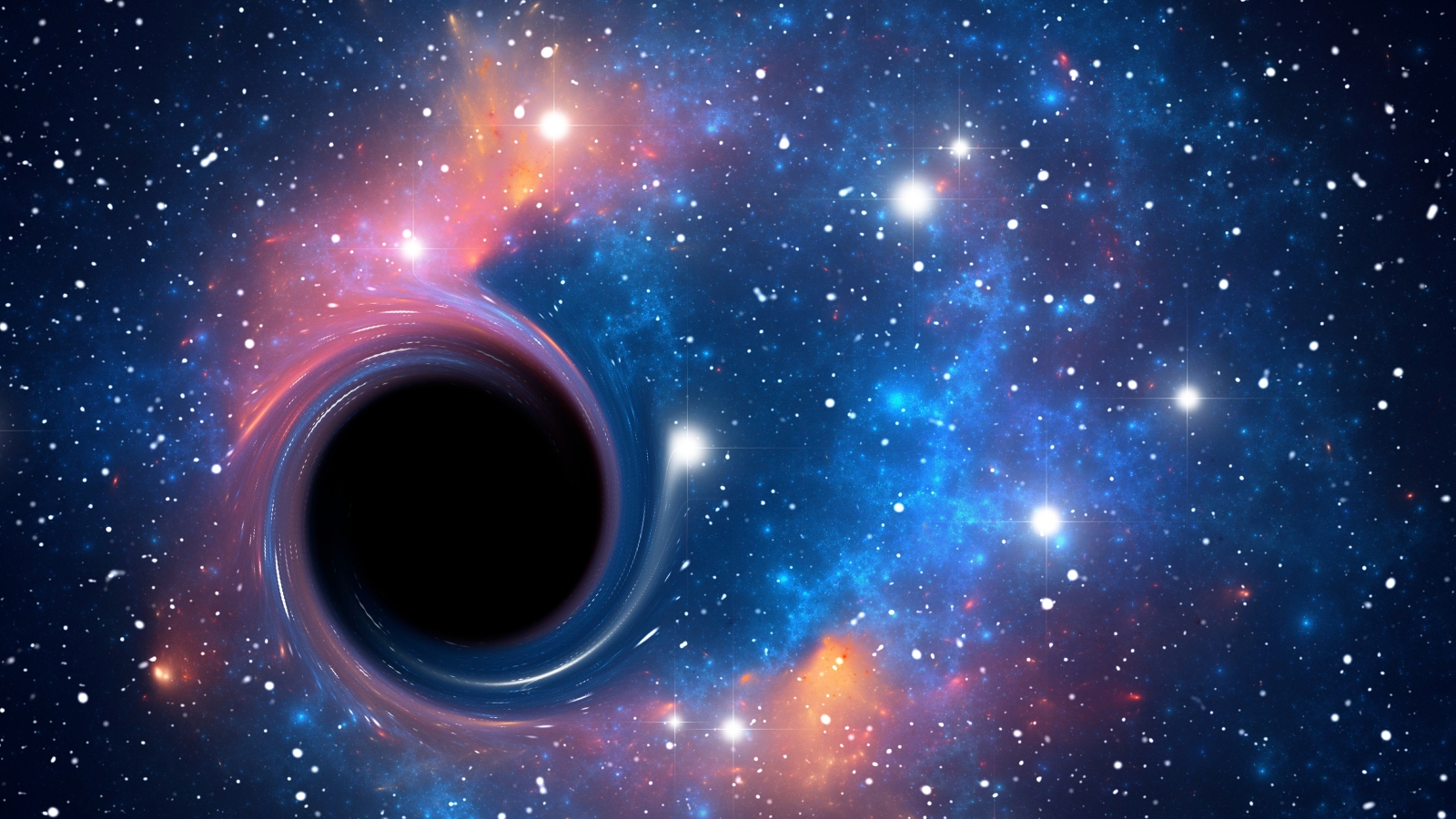

Black holes are terrifying, monstrous objects with immense gravity that causes them to consume everything that crosses their event horizons.

Yet the physics-breaking power of the space-time ruptures is also part of their draw — sucking in scientists who want to study the role of black holes in sculpting galaxies and those searching for a unified theory of gravity. Here are the most monstrous black hole findings of the year.

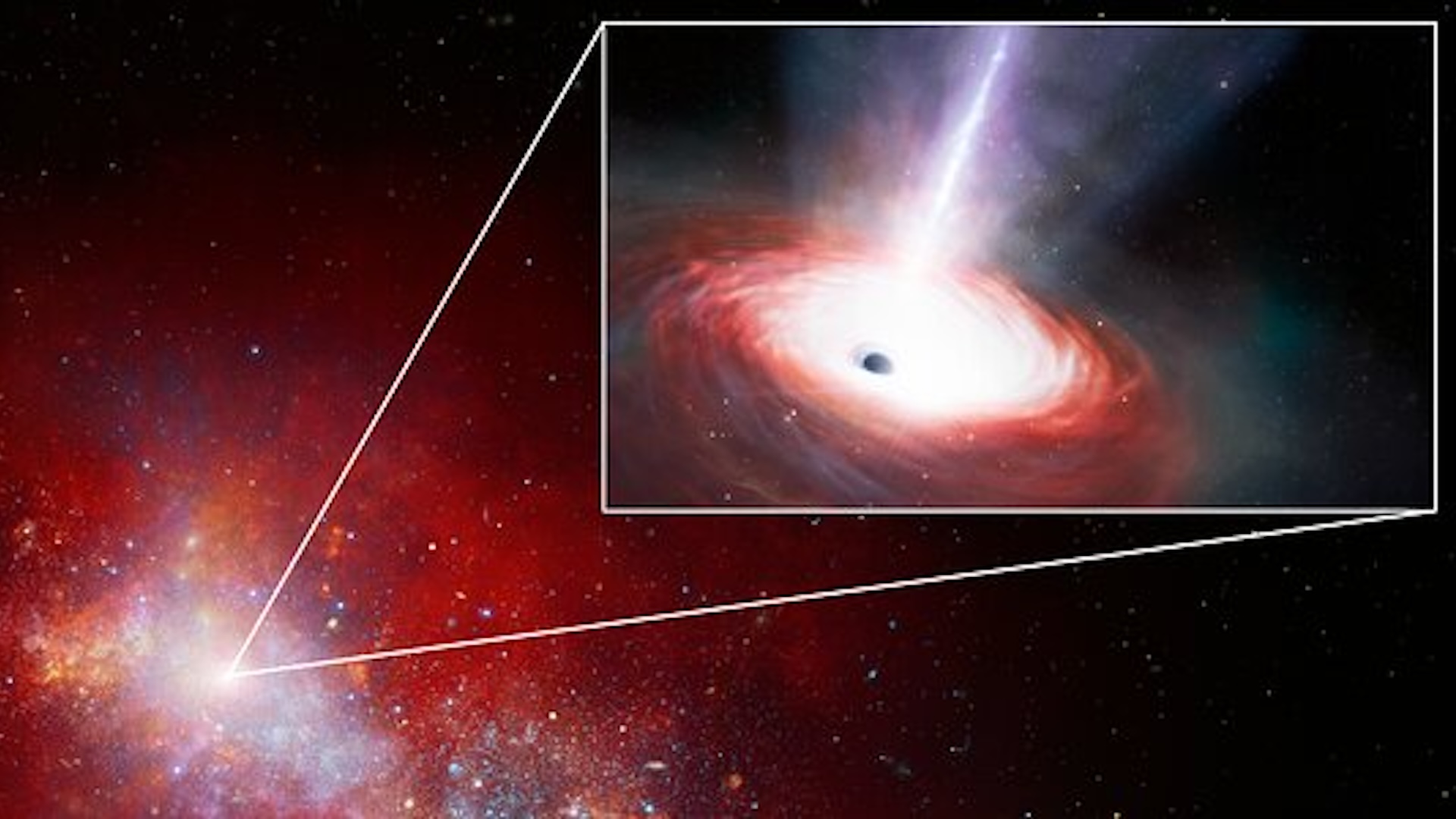

Scientists spot an ultra-rare "missing link" black hole hiding in the Milky Way's center

The known black holes that populate the universe fall into two types: those up to a few dozen times the mass of the sun and their supermassive counterparts that can weigh up to 50 billion solar masses. But exactly how the former evolved into the latter is unclear, especially as there have yet to be any confirmed sightings of black holes in their awkward intermediate phases.

Enter a new intermediate black hole candidate, which astronomers spotted inside the IRS 13 star cluster, just a tenth of a light-year from Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way galaxy. If scientists can confirm its existence, it could give vital clues to how black holes evolve.

A feasting supermassive black hole is consuming material 40 times faster than should be possible

This year, scientists found another clue to how supermassive black holes grow to their unimaginable scales, in the form of the gluttonous monster LID-568.

The James Webb Space Telescope spotted the black hole as it appeared just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, and it was gobbling material 40 times faster than its theoretical feeding limit (called the Eddington limit). The discovery could explain why so many giant black holes appear so early in the universe's history.

"Impossible" black holes discovered by the James Webb telescope may finally have an explanation

The finding about LID-568's feeding frenzy was far from the last word on early supermassive black hole formation. Theoreticians also proposed how black holes came to be seeded across the universe without, as they typically do today, emerging from dead stars: by rapidly collapsing pockets of gas that formed primordial black holes.

Most of these tiny singularities evaporated, according to the new hypothesis, but the ones that survived gorged and merged at a breakneck pace to reach their enormous scales.

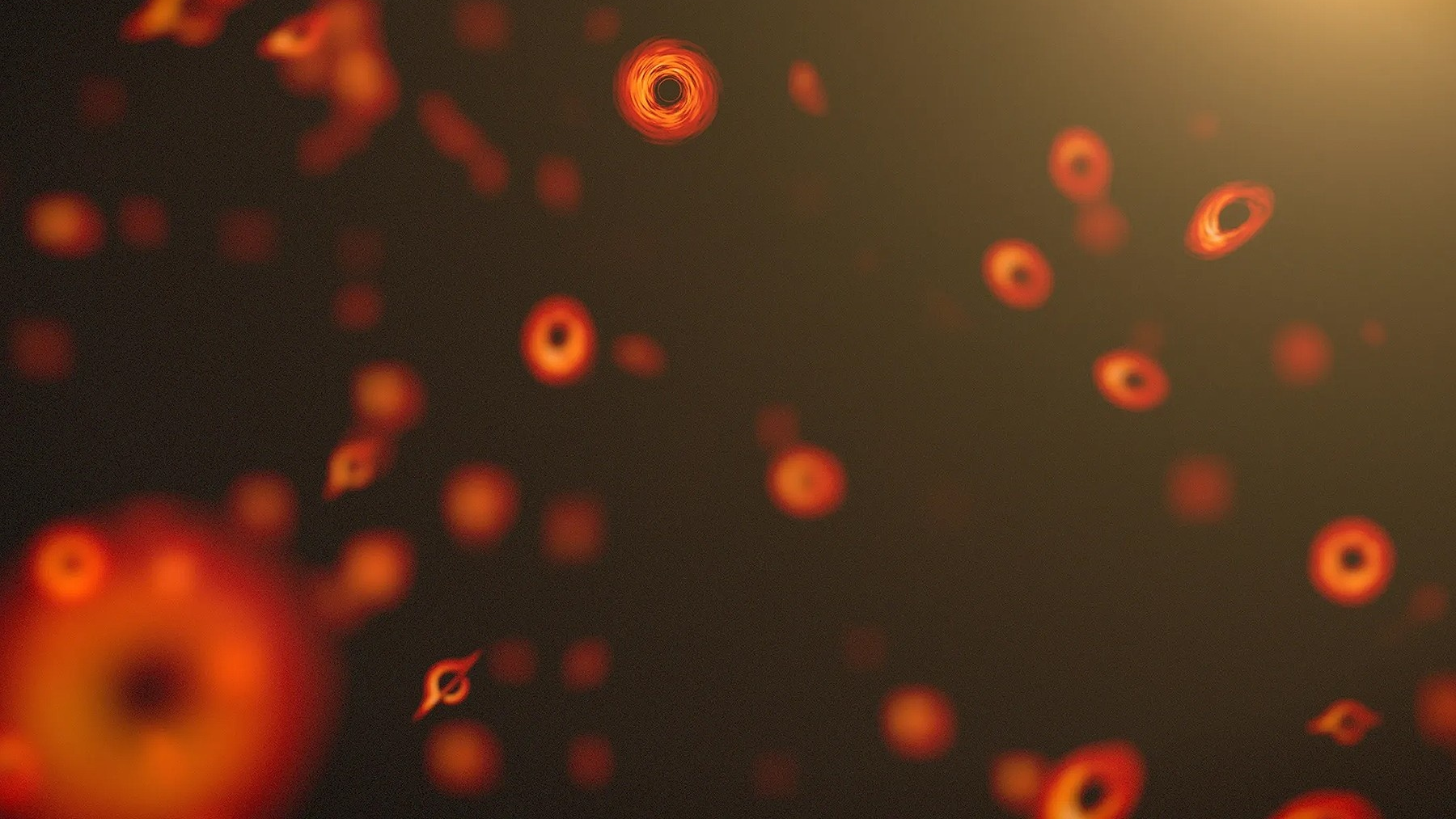

Tiny black holes could be hollowing out planets and zipping through our bodies

Another theoretical proposal about primordial black holes also made waves this year: the suggestion that they might still exist. Perhaps they're hollowing out planets and zipping through our bodies and buildings, leaving only microscopic traces.

If bits of tiny black holes swarming across the cosmos can be found, they would be immediate candidates for most of the missing matter that seems to exert a gravitational pull yet barely interacts with light.

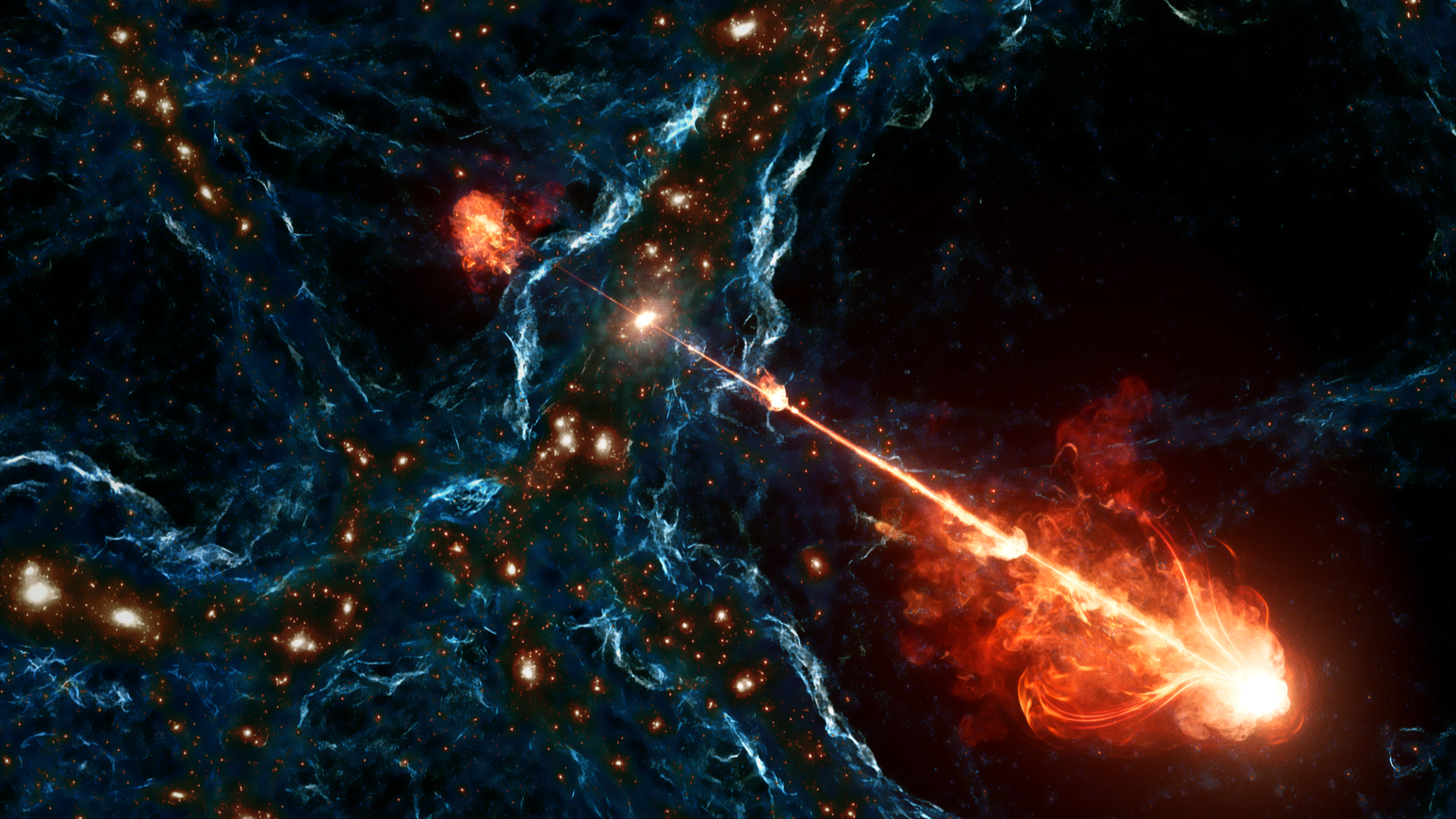

Biggest black hole jets ever seen are as long as 140 Milky Ways

Some black holes spew infalling matter out again, forming gigantic, near-light-speed plasma jets that can extend for hundreds of light-years. But one black hole jet pair astronomers spotted — named Porphyrion, after a giant in Greek mythology — really took the cake: At 23 million light-years in length, the pair is as long as 140 Milky Way galaxies laid end to end.

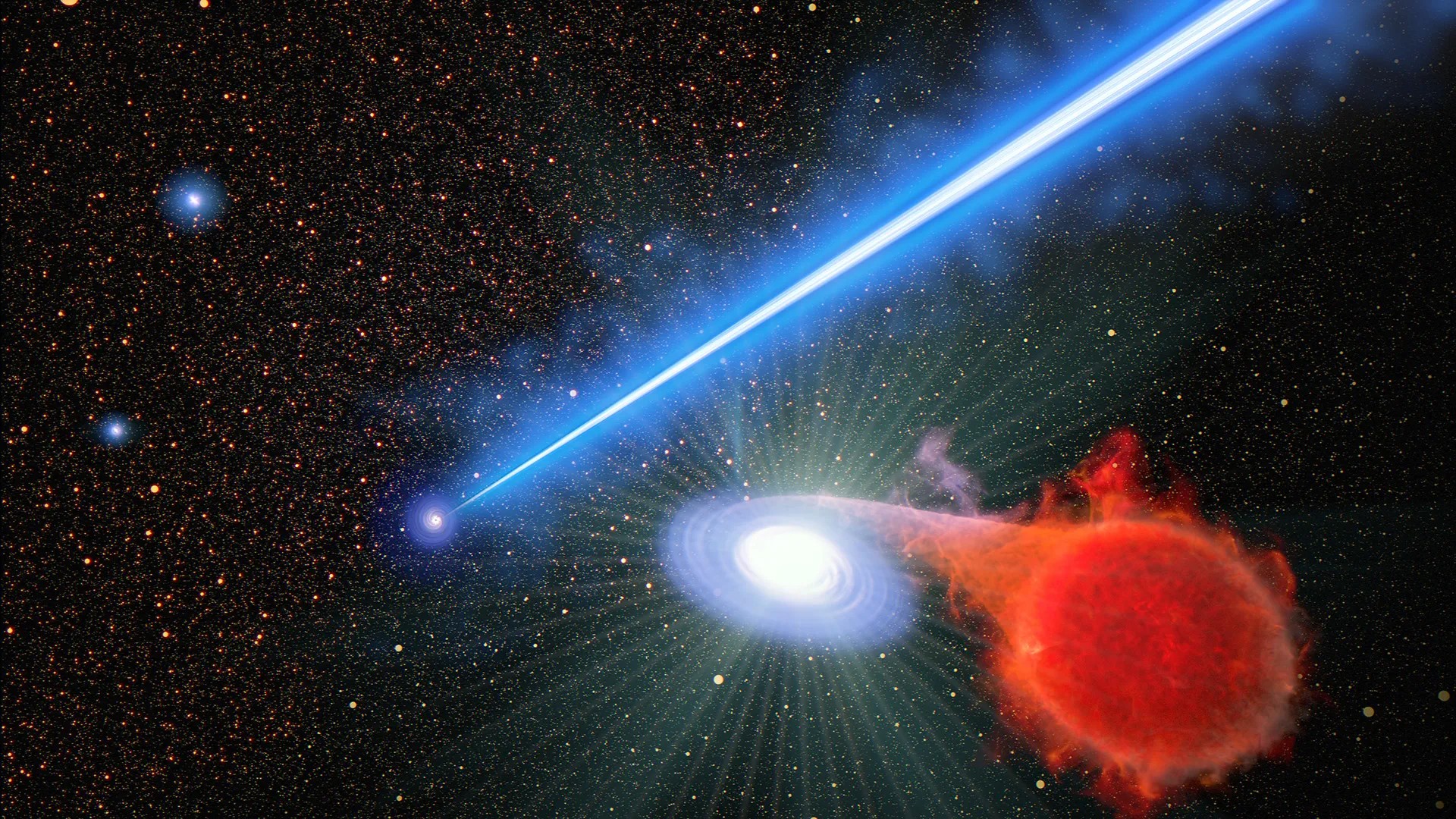

Black hole "blowtorch" is causing nearby stars to explode

Black hole jets aren't just incredible features. They're a powerful — yet still mysterious — force for the cosmic monsters to shape the wider universe. For the first time, researchers have observed a black hole jet causing stars in its vicinity to burst in explosions called novas.

Because the stars weren't directly hit by the beam, exactly how the jet is causing the stars to pop is unknown. By searching for answers, astronomers could gain a better understanding of how black holes affect even extremely distant surroundings.

Astronomers discover why some black holes have a "heartbeat"

While feeding, black holes can heat up their "food" to immense temperatures to release enormous X-ray flares that last millions of years. But inside these flares lurks another, strange signal: a regular pulse of light that resembles a heartbeat. By studying one of the flares, astronomers now think they have an explanation for black hole heartbeats: They're produced by shock waves that ripple through black holes' food as they feast.

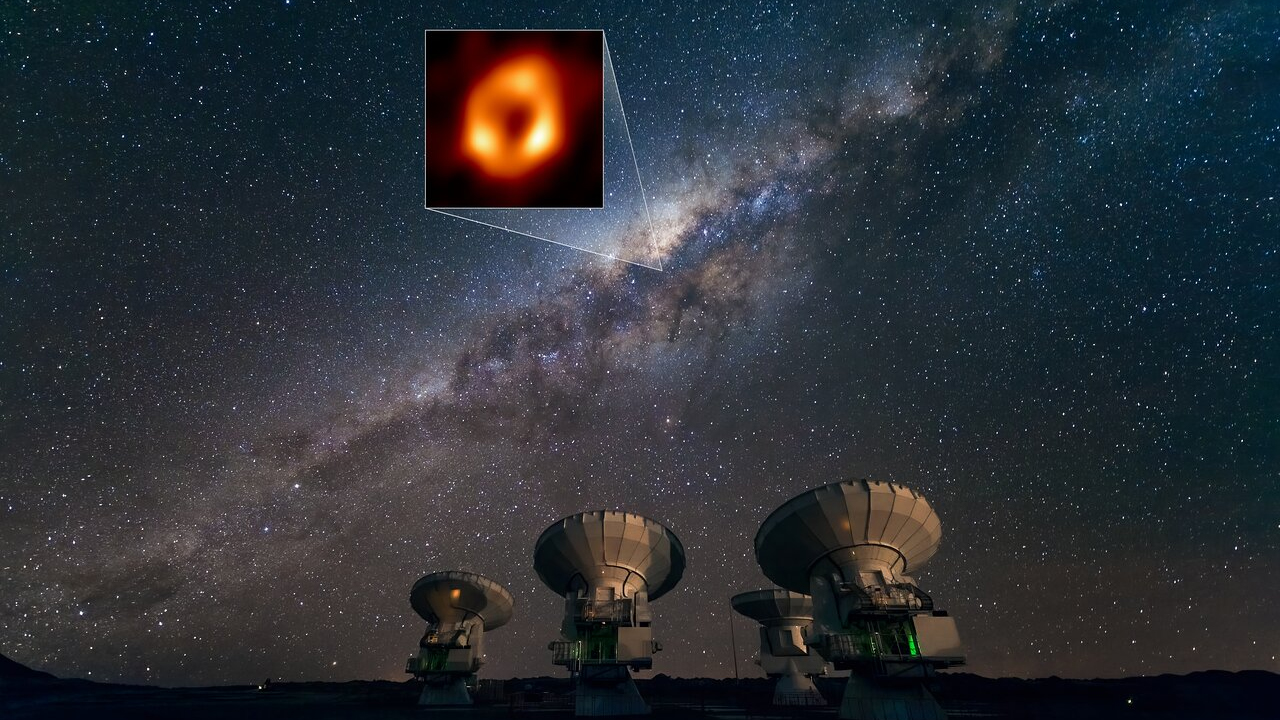

Event Horizon Telescope reveals why our galaxy's black hole is spinning so weirdly

Our galaxy's central black hole, Sagittarius A*, is a gargantuan tear in space-time that is 4 million times the mass of the sun and 14.6 million miles (23.5 million kilometers) wide. But these are pretty standard proportions for a black hole of this scale. What is unusual about Sagittarius A* is that it's spinning surprisingly fast and it's out of kilter with the rest of the Milky Way.

This year, using the Event Horizon Telescope, which in 2022 captured the first image of our galaxy's black hole, scientists found the answer: Sagittarius A* was likely born from a gigantic collision between two giant black holes, and its lopsided rotation is a key sign of its violent origins.

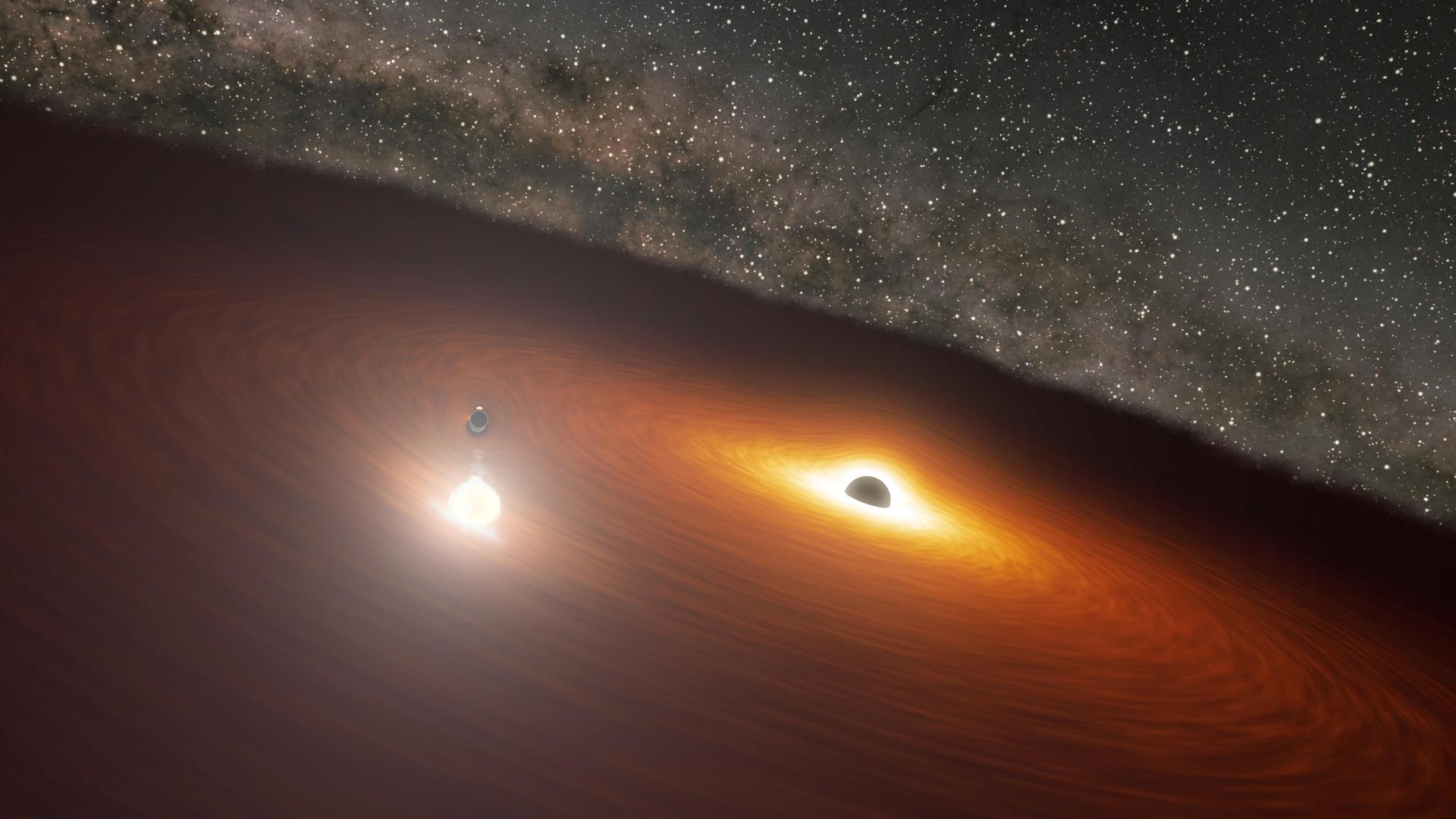

Scientists spot the first black hole "triple" system

Many black holes exist in binary systems, orbiting a star companion, but researchers have now spotted one orbited by two stars, making it the first black hole triple system ever seen. Beyond creating an entirely new category in its own right, the discovery has serious implications for black hole formation.

Black holes that exist in binary systems are typically thought to have emerged from the gravitational collapse of a star. But astronomers say this triplet could offer firsthand evidence of black holes directly collapsing from gas clouds.

Dormant black hole roars to life

Black holes are typically either active and consuming material around them, or dormant because they have already swallowed everything in their midst. It's rare to see black holes shift between the two states. But astronomers have now spotted a black hole that's waking up after a long slumber.

The reasons for the black hole's reactivation remain unclear, but astronomers hypothesize that it may have begun to capture new material. Alternatively, the light coming from near the space-time singularity star that it has snared and exploded.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality