The 8 most controversial science stories of 2024

From a piece of cloth that may have belonged to Alexander the Great to an image of our galaxy's central black hole, here's our pick of controversial science stories in 2024.

Disagreements about research results aren't often aired in the open, but this year saw its fair share of public scientific controversies.

Debates between scientists are usually confined to the pages of scientific journals, with researchers criticizing one another's work via letters and commentaries. Occasionally, though, these disputes spill out into the wider media, and they can range from squabbles over dinosaur bones to huge controversies around key archaeological artifacts.

This year, scientists argued about everything from climate change, to space junk to black holes. Here is our list of 2024's most controversial science stories.

Building world's 1st pyramid

In a preprint study published this summer, researchers proposed that ancient Egyptians built the world's first pyramid — the 4,700-year-old Step Pyramid of Djoser, which sits on Egypt's Saqqara plateau — using a "modern hydraulic system" powered by a long-gone branch of the Nile River. The system comprised a dam, a water treatment plant and a hydraulic freight elevator, the researchers suggested, enabling workers to deliver heavy construction materials to the pyramid building site.

The proposed infrastructure addresses long-standing questions about how ancient Egyptians erected the Step Pyramid of Djoser, which contains 11.6 million cubic feet (330,400 cubic meters) of stone and clay, before the advent of large machinery like bulldozers and cranes. Study lead author Xavier Landreau told Live Science the hydraulic system was "a watershed discovery," but another expert wasn't so sure about the findings.

Julia Budka, an archaeologist specializing in ancient Egypt at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany, told Live Science that "scientifically, their hypothesis is not proven at all." Budka added: "My biggest concerns about the study are that no Egyptologists or archaeologists were directly involved and that the authors actually question the use of the Djoser Pyramid as a burial site." (Peer-reviewed research shows the pyramid was in fact used as a burial site.)

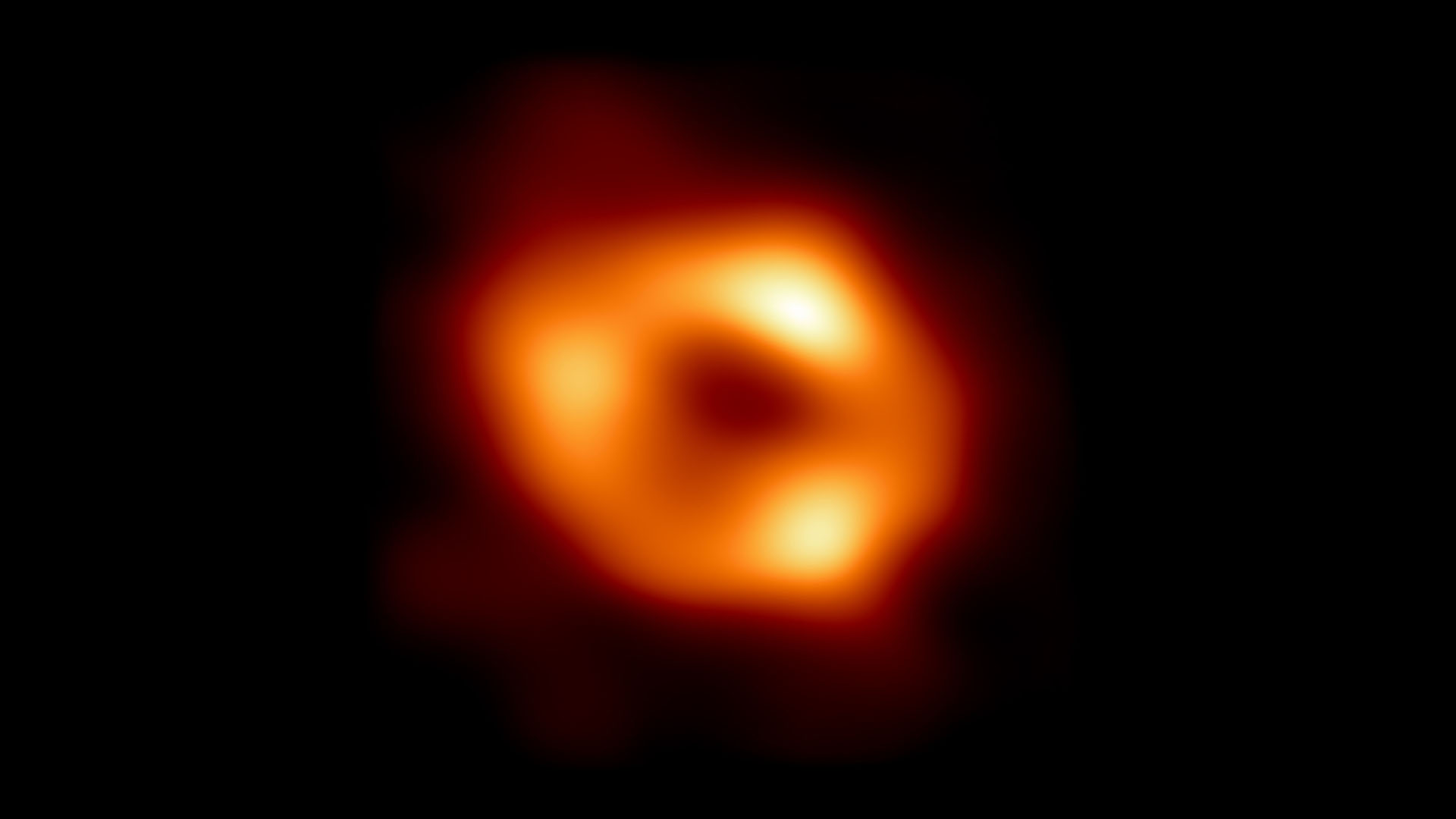

Black hole image

A groundbreaking picture of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole that sits at the center of the Milky Way, caused a stir this year, with a study published online in May claiming the image displays important errors. The photo, which was taken with the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) in 2017 and released in 2022, is the first ever image of our galaxy's central black hole, located 26,000 light-years from Earth.

The image shows an orange, donut-shaped ring of gas against a pitch-black background — but researchers say the ring is distorted due to the way the data for the image were stitched together. The ring should be more elongated than it appears in the image, the researchers said, and the eastern half should be brighter than the western half.

"We hypothesize that the ring image resulted from errors during EHT's imaging analysis and that part of it was an artifact, rather than the actual astronomical structure," study lead author Makoto Miyoshi, an astronomer at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, said in a statement at the time.

The EHT team responded to the claims in November saying that their methods were extensively verified, and their results consistent over two days of observations. The team pointed out inconsistencies in the revised image, arguing that Miyoshi and colleagues mistook "the biases in their own methodology as demonstrations of biases" in the original EHT methods.

Global warming's beginning

A study published early this year found Earth is on course to reach 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) of warming relative to preindustrial levels by the late 2020s — more than a decade earlier than current projections. Global warming of 2 C is considered a critical threshold to prevent the worst effects of climate change; warming beyond this would greatly boost the likelihood of extreme weather and other destructive impacts.

The study authors said in a news conference that their results mark "a major change to the thinking about global warming," because they bring forward the advent of human-made climate change by four decades, meaning scientists have been underestimating the level of warming all along. The United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that global warming began around 1900, but the recent study says the start date is more likely to have been in the 1860s.

The authors based their results on climate indicators found in old skeletons of sponges from the Caribbean Sea. But other experts criticized the findings, saying the authors wrongly extrapolated from highly local data to draw conclusions about the whole world. "The study fails to support its global claims with robust evidence, and it fails by a huge margin," Jochem Marotzke, a professor of climate science and director of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Germany, told Live Science.

"Skepticism is warranted here," Michael Mann, director of the Penn Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media, told Live Science. "It honestly doesn't make sense to me."

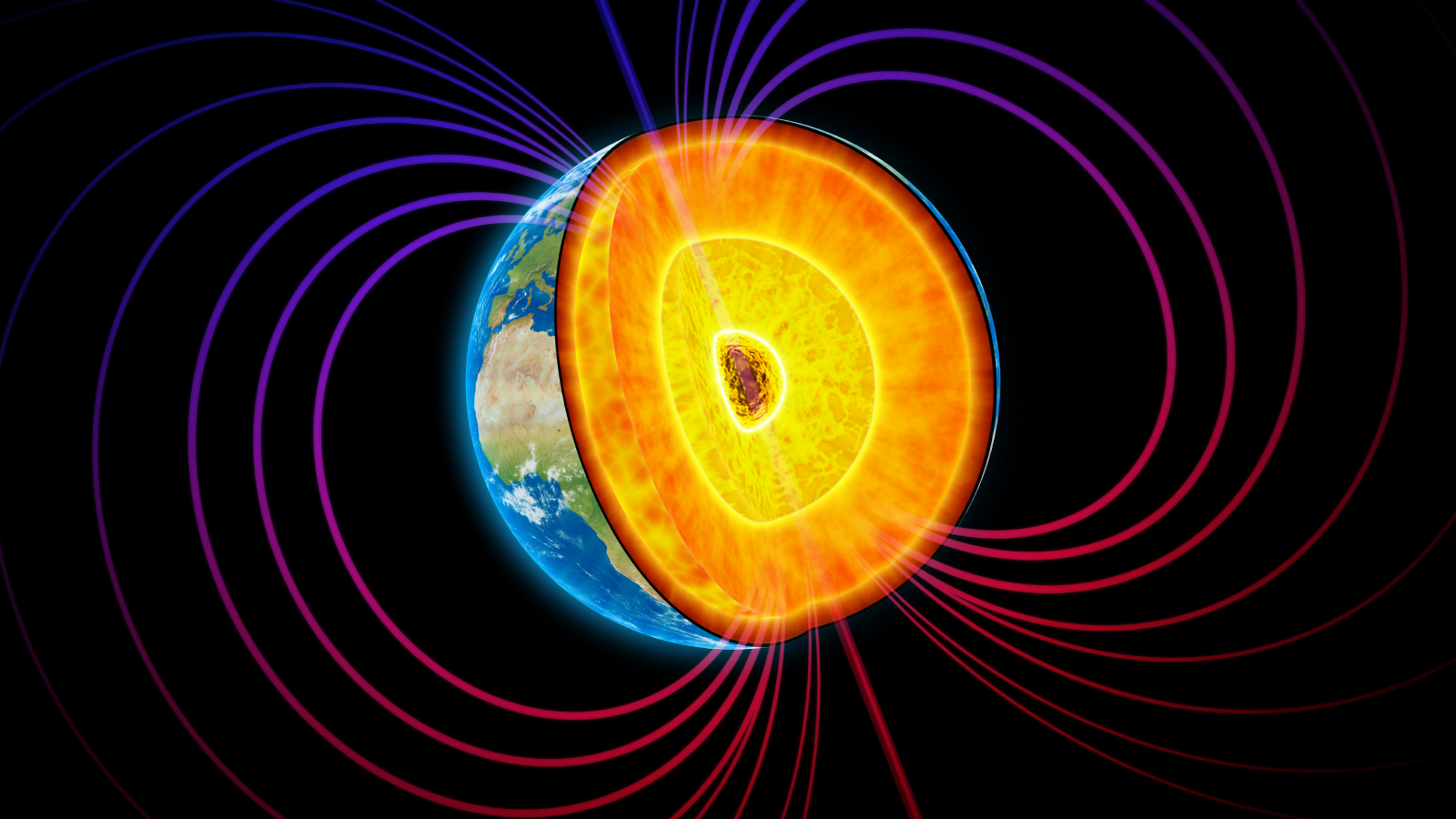

Weakening Earth's magnetic field

Defunct satellites that burn up as they enter Earth's atmosphere could be releasing dust that interferes with the planet's magnetic field, according to a preprint study that attracted criticism this year. Metal pollution from falling space junk may theoretically create an invisible conductive shell around Earth, weakening the magnetosphere — the bullet-shaped field around Earth that stretches roughly 39,800 miles (64,000 kilometers) above our planet's surface.

The metal pollution, a problem that is being made worse by the unchecked expansion of commercial satellites orbiting Earth, could slice the magnetosphere in half and lead to "atmospheric stripping" down the line, study author Sierra Solter-Hunt, who was then a doctoral candidate at the University of Iceland, told Live Science. Although this is a worst-case scenario, the findings are "really, really alarming," Solter-Hunt said.

Some scientists praised the study for highlighting potential issues arising from spacecraft dust, but others said the results were too speculative or based on flawed assumptions. "Even at the densities [of spacecraft dust] discussed, a continuous conductive shell like a true magnetic shield is unlikely," John Tarduno, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Rochester in New York, told Live Science.

Nevertheless, space junk pollution "is not an issue to be ignored," said Fionagh Thompson, a research fellow at Durham University in the U.K. "There is a need to step back and view this as a completely new phenomenon."

Baby T. rex or tiny dino?

A study in January weighed in on a long-standing debate over a set of dinosaur fossils that could belong either to a young Tyrannosaurus rex or to a distinct species called Nanotyrannus lancensis. The study supported the Nanotyrannus hypothesis, based on growth rings on the fossils, and claimed to snuff out the opposing side of the dispute once and for all — but other experts still weren't convinced.

The study authors found that growth rings were closely packed toward the outside of the bones, which is inconsistent with the rapid growth of a dinosaur, and therefore refutes the juvenile T. rex hypothesis, they said. "If they were young T. rex they should be growing like crazy," lead author Nicholas Longrich, a paleontologist and senior lecturer at the University of Bath in the U.K., said in a statement at the time. Instead, the bones showed a pattern consistent with slowing growth, Longrich said.

But some experts remained resolutely team T. rex. "The authors don't seem to have a solid grasp on growth variation in tyrannosaurs," Thomas Carr, a vertebrate paleontologist and an associate professor of biology at Carthage College in Wisconsin, told Live Science. Others said they will sit on the fence until fossils come to light that belong to either a fully adult Nanotyrannus or a young T. rex that definitely isn't Nanotyrannus — at which point comparison work could settle the question once and for all.

Alexander the Great's lost tunic?

A scrap of cloth discovered decades ago in a royal tomb belonged to none other than Alexander the Great, according to a controversial study published in October. Located in Greece, the tomb is generally believed to hold the remains of Alexander's father, Philip II, but the study argues it actually belongs to Alexander's half-brother, Philip III. Therefore, the cloth inside was once part of a sacred tunic worn by Alexander that, after his death, was passed on to Philip III and accompanied him to his grave, the author claimed.

The study's conclusions are based on multiple lines of evidence — such as the art on the tomb's walls, studies of the skeletons found inside and ancient records of garments worn by different kings — but the findings sparked mixed reactions from experts. Some researchers said there is no evidence to support the idea that the cloth formed part of a tunic, while others noted that the author of the study never actually saw the piece of material, discrediting the paper's conclusions.

Another group of researchers, meanwhile, thought the case for the cloth being Alexander's lost tunic was strong.

AI fingerprint-matching tool

A new technique to match fingerprints from separate digits belonging to the same person sparked controversy at the beginning of 2024. It's long been suspected that connecting prints from different digits could help solve criminal cases, but forensic methods so far haven't been able to do so accurately, only reliably linking fingerprints from the same digit.

Researchers used artificial intelligence (AI) to develop a tool that can connect different fingerprints left by the same person 77% of the time, based on similarities between the angles of arches, whorls and loops on each finger. The study in which they detailed their methods was rejected by several journals but was eventually published, receiving mixed reactions from other experts.

Simon Cole, a professor of criminology, law and society at the University of California, Irvine, said the study was "overhyped" and only had "rare and limited use," given that law enforcement routinely takes prints from all 10 digits and can match prints simply by looking at records.

Ralph Ristenbatt, a criminalist and assistant teaching professor of forensic science at Pennsylvania State University, argued the technique could prove useful in certain cases. But more work is needed until the AI tool is accurate enough to be rolled out and used in a court of law.

Megalodon misrepresented?

A new analysis of megalodon fossils published in January found that the long-extinct, supersized sharks looked nothing like researchers previously thought. Reconstructions to date indicated that megalodons (Otodus megalodon) measured around 52 feet (16 meters) long and resembled great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), but this body shape "looked very awkward," according to the authors of the new study.

The anatomy of megalodon has remained somewhat elusive because shark skeletons are made of cartilage rather than bone, and therefore don't preserve well as fossils. Scientists mostly only had fossilized teeth and vertebrae to work with, so they often used great white sharks as models to establish what megalodon looked like.

The analysis in January found megalodons were much slimmer and longer than great whites, with a body plan closer to that of a shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus). The evidence suggested the meg may have reached 66 feet (20 m) long or possibly slightly more, the authors told Live Science. But other researchers who had previously examined megalodon fossils weren't convinced by the findings.

According to them, the analysis used "circular logic," where an argument uses the assumption that its conclusion is correct to support itself. "The 'elongated body' interpretation is based on a single observation, a comparison with a single analogue, and lacks any statistical tests to support its hypothesis," Jack Cooper, a researcher at Swansea University in the U.K., Catalina Pimiento, also of Swansea University, and John Hutchinson from the Royal Veterinary College in London told Live Science. The study is also impossible to fully verify as the authors held back crucial data, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.