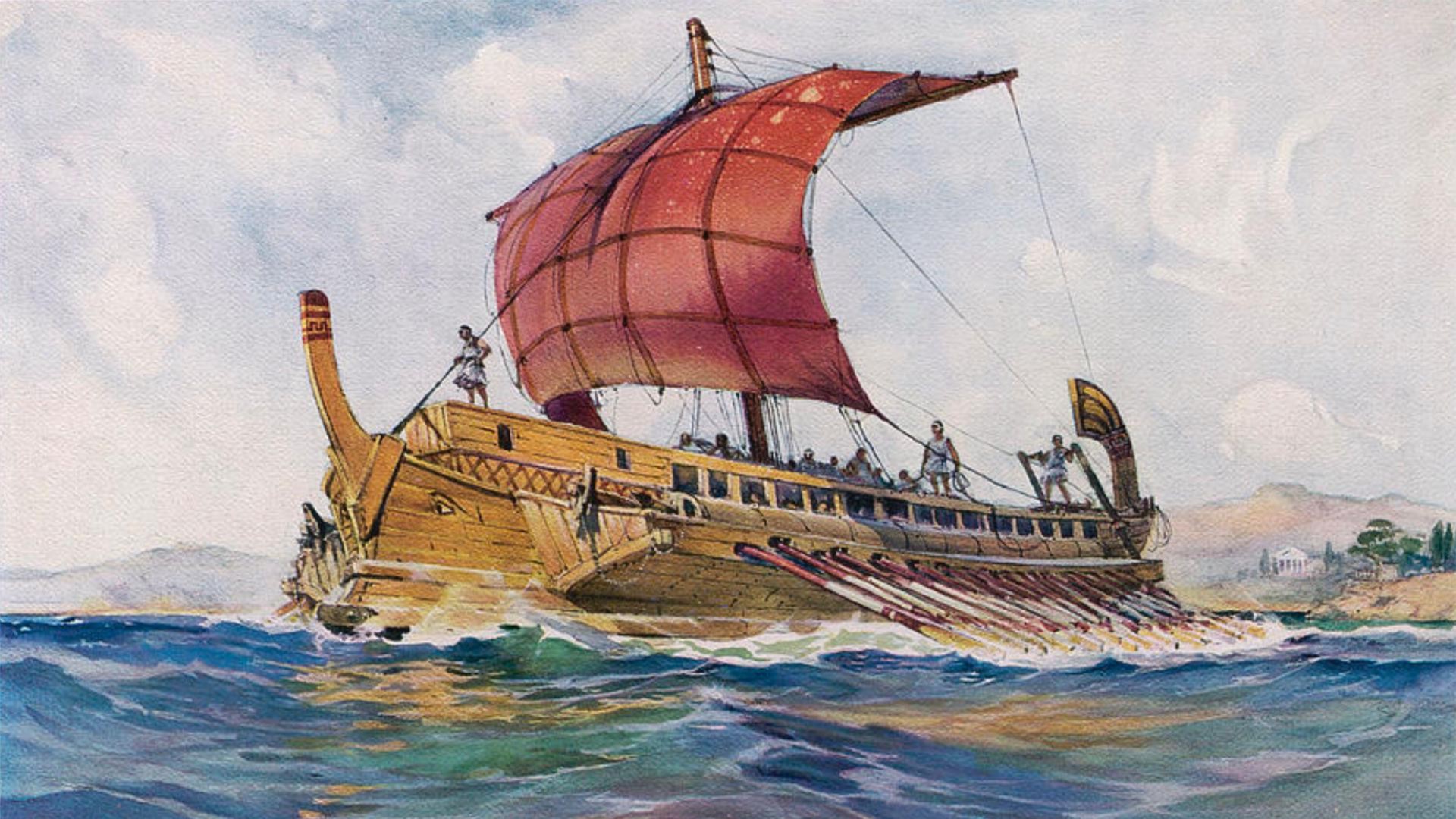

Once upon a time — at least according to the ancient Greek writer Plutarch — the hero Theseus sailed from Athens, Greece, to the island of Crete, where he slayed the half-man, half-bull Minotaur before sailing back to rule Athens.

The wooden ship that Theseus sailed on, Plutarch imagined, must have become a national treasure, and he posed a thought experiment that has fascinated philosophers ever since: If you repaired Theseus' ship plank by plank so that no original planks remained, is it still the same ship?

"The people who've been sailing the ship will say, 'Yeah, it's the same ship! We've been sailing for years, and we just keep fixing it,'" said Michael Rea, director of the Center for Philosophy of Religion at the University of Notre Dame.

"But you can imagine a collector wanting to put the original ship in the museum," Rea told Live Science. "She goes and gathers up all the original planks, rebuilds them and says, 'I've got the ship of Theseus!' So, the question is, which one is the ship?"

Related: What is Occam's razor?

Variations of the ship of Theseus thought experiment pop up everywhere. In Marvel Studios' "WandaVision," Vision comes face-to-face with a duplicate self and must figure out who is the real Vision. In "The Good Place," Chidi Anagonye lives hundreds of separate lives and must confront which, if any, represents his real self. In other eras, people have asked if an ax still counts as George Washington's ax if both the handle and the ax head are replaced.

"It looks like just a dumb party puzzle, right?" Rea said. "But you can learn a lot by thinking through these puzzles really carefully."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ship of Theseus thought experiment raises questions about the material composition of objects: Is the ship the sum of its planks, the sum of its sailing history or both at once? Can objects made up of other objects even be said to exist?

To answer those questions, philosophers must deal with conundrums such as whether two things can occupy the same place at the same time, how parts relate to a whole and how to think about the nature of time.

One answer, Rea said, is to say that only the planks are real and the ship "is just a phase." Taken to its logical extreme, this answer, nihilism, implies that only fundamental particles exist; objects made up of multiple parts are just an illusion.

But perhaps ships do exist; if so, maybe they are defined by their parts. In that case, Rea said, "the museum curator is correct." If objects can survive part replacement — our cells, for example, are constantly dying and being replaced — then maybe the ship at sea is the real ship.

Or maybe there have been two ships all along, sometimes sharing the same location. In that case, Rea said, "The words 'ship of Theseus' were ambiguous, and that's why now we're all confused."

If two objects can be in the same place at the same time, it opens up a whole new can of worms — space-time worms, to be exact.

Perhaps the ship of Theseus exists as many overlapping chunks of space-time: The ship in the moment when the first plank was replaced, the ship as it was when Theseus walked the decks and the ship's entire existence, from the growing trees that become its planks to its afterlife as a philosophical thought problem.

Related: Where does the concept of time travel come from?

All of these ships together can be said to "perdure." "If I perdure, I'm this four-dimensionally extended thing," Rea said. "People started calling those space-time worms." This view usually goes hand-in-hand with the idea that the past and the future exist — a philosophical stance called four-dimensionalism — in contrast to presentism, a theory of time in which only the present moment is real.

None of this philosophical groundwork, however, can definitively say which ship is the real ship.

"I think that it is very interesting that we have this question at all," said Anne Sauka, a philosopher at the University of Latvia. The question itself assumes a particular ontology, or theory of being.

She told Live Science that the ship of Theseus puzzle makes the most sense in the context of substance ontology, in which objects are the focus of philosophical interest. The alternative is a process ontology, which sees change as more fundamentally real than objects.

Seen that way, the planks, the ships and Theseus himself are not static things but rather processes that are always shifting. Trying to claim either ship for Theseus demonstrates an unwillingness to let either ship evolve into something new. "The question itself shows that we have a problem with change," Sauka said.

The ship of Theseus can also be seen as a metaphor for the self: "If we change, are we a different person?" Sauka said. In process ontology, change is the starting point. "Selfhood is something that only happens by virtue of change," she said. Death "is just the dissolving of that particular process that was a stable process for a time."

Meg Duff is a freelance science journalist and audio producer based in Brooklyn. She holds an M.F.A from New York University's Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute. Her stories have also appeared in Slate Magazine, Scientific American, MIT Technology Review, and elsewhere.