20,000-year-old cave painting 'dots' are the earliest written language, study claims. But not everyone agrees.

Stone Age dots, lines and Y-shaped marks might represent a type of proto-writing created by hunter-gatherers who lived in Europe at least 20,000 years ago.

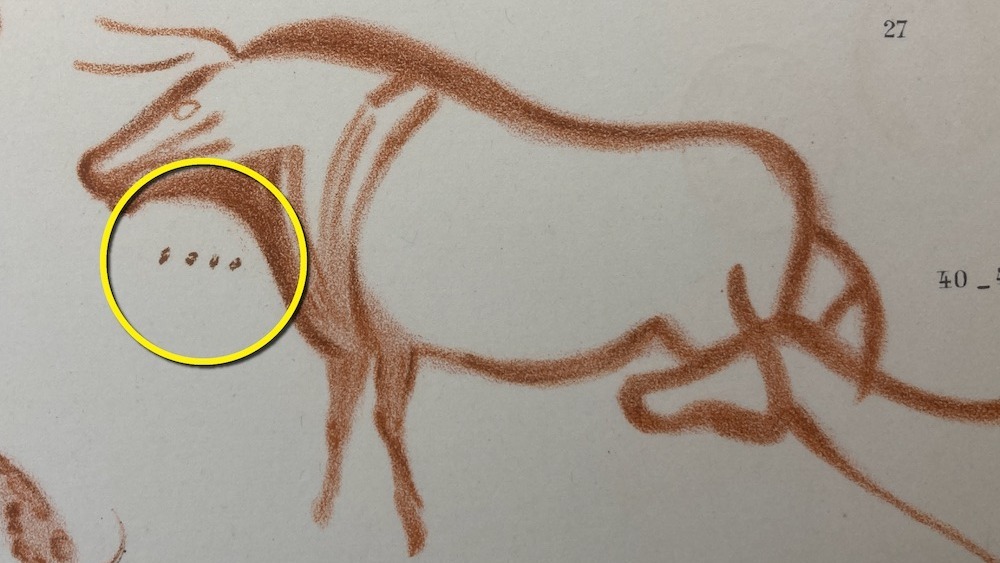

At least 20,000 years ago, humans living in Europe created striking cave paintings of animals that they paired with curious signs: lines, dots and Y-shaped symbols. These marks, which are well known to researchers, might relate to the seasonal behavior of prey animals, making the signs the first known writing in the history of humankind, a new study claims.

Although Paleolithic cave art is better known for its graceful horses and ghostly handprints, there are thousands of nonfigurative or abstract marks that researchers have begun studying only in the past few decades. In a study published Jan. 5 in the Cambridge Archaeology Journal, a team of scholars suggests that these seemingly abstract dots and lines, when positioned near animal imagery, actually represent a sophisticated writing system that explains early humans' understanding of the mating and birthing seasons of important local species.

Other researchers, however, are not convinced by the study's interpretations of these human-made marks.

Melanie Chang, a paleoanthropologist at Portland State University who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that she agrees with the researchers' assessment that "Upper Palaeolithic people had the cognitive capacity to write and to keep records of time." However, she cautioned that the researchers' "hypotheses are not well-supported by their results, and they also do not address alternative interpretations of the marks they analyzed."

Related: Back to the Stone Age: 17 key milestones in Paleolithic life

What do the painted marks mean?

Early humans in Europe were hunter-gatherers who ate a lot of meat from species such as horses, deer and bison. When those animals came together seasonally in herds, they would have been vulnerable to slaughter by humans. "It follows that knowledge of the timing of migrations, mating and birthing would be a central concern to Upper Paleolithic behaviour," study first author Bennett Bacon, an independent researcher and furniture conservator based in London, and colleagues wrote in their study.

Looking at the total number of marks — either dots or lines — found in sequences across hundreds of caves, the researchers discovered that none of the series contained more than 13 marks, consistent with the 13 lunar months in each year. "We hypothesize that sequences are conveying information about their associated animal taxa in units of months," they wrote, noting that spring, "with its obvious signals of the end of winter and corresponding faunal migrations to breeding grounds, would have provided an obvious, if regionally differing, point of origin for the lunar calendar."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers' statistical analysis of more than 800 sequences of marks associated with animals supports their idea — they found strong correlations between the number of marks and the lunar months in which the specific animal is known to mate.

Taking their hypothesis a step further, Bacon and colleagues focused on a Y-shaped sign that they think refers to a particular event in an animal's life cycle. Similar statistical analysis supports their conclusion that the placement of the Y-shaped sign within a series of marks signals an animal species' birthing season.

"The ability to assign abstract signs to phenomena in the world," they wote, "to record past events and predict future events, was a profound intellectual achievement."

Writing or proto-writing?

But is this the earliest known writing? Bacon and colleagues demur, suggesting that "it is best described as a proto-writing system, an intermediary step between a simpler notation/convention and full-blown writing."

April Nowell, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Victoria in Canada who was not involved in this study, told Live Science by email that "any study that explores non-figurative signs in more detail is welcome, but I think there are a number of assumptions being made here that have yet to be proven." Nowell questioned the Y sign, in particular. "The majority of animals considered in this study are quadrupeds, and humans normally squat giving birth," she said. "If this sign is supposed to be iconic of the birth process, it is not obvious to me."

Related: One of the oldest written sentences on record blasts hair and beard lice

Chang, the paleoanthropologist who is also an equestrian and horse owner, posed two alternative explanations for the Y sign. In some cases, it could represent the edge of the brachiocephalic muscle, a prominent landmark on a horse's neck. "In other cases," she said, "it is possible that what they recorded as Y's represent what modern horsepeople refer to as 'primitive markings' such as leg bars that are associated with wild-type horse colors, or they may represent hair patterns, or other anatomical features."

Study co-author Robert Kentridge, a professor in the Department of Psychology at Durham University in the U.K., told Live Science in an email that one of the strengths of their study is that they "have formally tested Ben [Bacon's] hypotheses about the meaning of the Y-sign's position in sequences of marks and the lengths of sequences of dots and lines and shown that these do convey meaning, indeed meaning that would be important in the lives of Palaeolithic hunters."

In summarizing their conclusions, Bacon and colleagues wrote that they have "proposed the existence of a notational system associated with an unambiguous animal subject relating to biologically significant events" and that this allows them "for the first time to understand a Palaeolithic notational system in its entirety."

A decade ago, however, Nowell and then-graduate student Genevieve von Petzinger co-created a database of dozens of signs and repeating motifs from more than 200 caves in southern France and Spain. Von Petzinger's thesis detailed patterns of cave wall symbols across time and space in order to better understand what these signs meant for ice age people. "There are at least 32 different recurring signs," Nowell explained. "The authors have chosen to study three of them in a very specific context."

But the authors defended their decision to focus on the trio.

"It seemed sensible to focus first on the most common markings associated with figurative images," study co-author Paul Pettitt, a professor of archaeology at Durham University, told Live Science in an email. "Simple dots and lines are by far the most common. Of the more elaborate signs, the Y sign is the most common."

The researchers plan to expand on their work. "We are analyzing other signs," Bacon told Live Science in an email. "Rather than searching for the meaning of individual signs, what we are looking for is the linguistic and cognitive bases that underpin the 'writing' system."

Nowell agreed with the study authors that the symbols were likely not randomly chosen and that it is possible the lines and dots represent numbers. Even if the authors are correct, she noted, that leaves 90% of the signs without any known meaning.

"There is still a lot about graphic communication in the Paleolithic that we do not understand," Nowell said.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.