Ice age children frolicked in 'giant sloth puddles' 11,000 years ago, footprints reveal

"All kids like to play with muddy puddles."

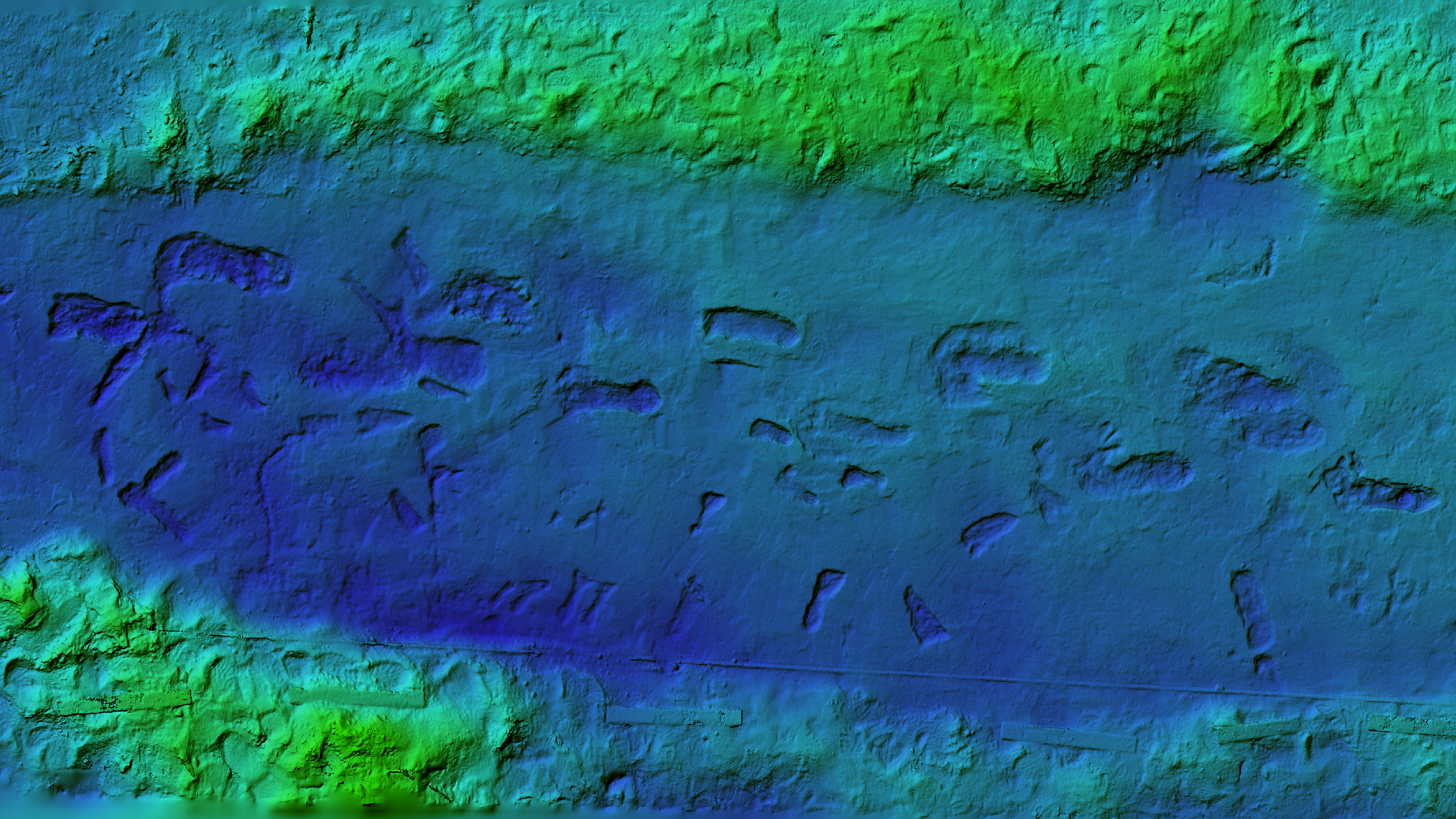

More than 11,000 years ago, young children trekking with their families through what is now White Sands National Park in New Mexico discovered the stuff of childhood dreams: muddy puddles made from the footprints of a giant ground sloth.

Few things are more enticing to a youngster than a muddy puddle. The children — likely four in all — raced and splashed through the soppy sloth trackway, leaving their own footprints stamped in the playa — a dried up lake bed. Those footprints were preserved over millennia, leaving evidence of this prehistoric caper, new research finds.

The finding shows that children living in North America during the Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) liked a good splash. "All kids like to play with muddy puddles, which is essentially what it is," Matthew Bennett, a professor of environmental and geographical sciences at Bournemouth University in the U.K. who is studying the trackway, told Live Science.

Related: Incredible fossilized footprints suggest that early humans stalked giant sloths

Bennett has traveled to White Sands more than a dozen times in the past five years, locating and analyzing footprints left by ice age humans and megafauna (animals heavier than 99 pounds, or 45 kilograms). He and his colleagues have already made a number of remarkable finds, including human footprints dating to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, which are the earliest 'unequivocal evidence' of people in the Americas.

The discovery of the children's and sloth's muddy prints haven't been published in a peer-reviewed journal, but Bennett plans to write about them in the coming months as a methods paper, to help scientists who are studying similar trackways determine how many people were present and how old those individuals were when they created the tracks. For instance, the tracks that Bennett analyzed aren't an accurate representation of the children's feet, as the squishy mud distorted each print, but Bennett was able to compare the preserved, smeary footprints with modern growth data to deduce the children's ages.

He found that there were more than 30 footprints crisscrossing the sloth trackway, likely from children between the ages of 5 and 8 years old, Bennett said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The now-extinct giant ground sloth, possibly Nothrotheriops, left its trackway after walking through the area on all fours. Each sloth print is actually a double print, Bennet said. "As it puts its forepaws down, the rear paw comes and steps on it," he explained. This combination of front and back paw gives the prints a kidney shape.

Each of the giant ground sloth footprints measures nearly 16 inches (40 centimeters) long, and the beast would have been anywhere from the size of a cow to as big as a bear, Bennet said. The footprints are shallow, about 1.2 inches (3 cm) deep, but it seems that was deep enough for them to fill with water and intrigue the children.

"We see children's tracks very frequently at White Sands," most likely because, just like today's children, these youngsters raced around, leaving hundreds of footprints a day, Bennett said.

The children and adults in the group were "almost certainly" foragers who stuck together while searching for food, he added. "In the past, you would have just taken your kid to work. And if work was walking across the former lake bed in order to track an animal, you would have taken your child with you."

It's challenging to date footprints without a detailed stratigraphy — or studying the rock layers — of the site and without finding any organic matter, which can be radiocarbon dated. But based on the discovery of the 23,000-year-old prints and the fact that ground sloths went extinct around 11,000 years ago, these once-splashy children’s prints were likely made between 23,000 and 11,000 years ago, Bennet said.

You can read more about the footprint finding on New Scientist.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.