Sprawling 8-mile-long 'canvas' of ice age beasts discovered hidden in Amazon rainforest

Ice age people painted these animals 12,600 years ago.

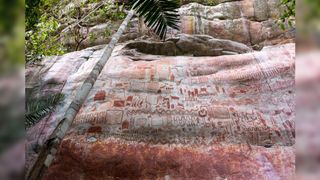

An 8-mile-long "canvas" filled with ice age drawings of mastodons, giant sloths and other extinct beasts has been discovered in the Amazon rainforest.

The gorgeous art, drawn with ochre — a red pigment frequently used as paint in the ancient world — spans nearly 8 miles (13 kilometers) of rock on the hills above three rock shelters in the Colombian Amazon, a new study finds.

"These really are incredible images, produced by the earliest people to live in western Amazonia," study co-researcher Mark Robinson, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter, who analyzed the rock art alongside Colombian scientists, said in a statement.

Related: 10 extinct giants that once roamed North America

Indigenous people likely started painting these images at the archaeological site of Serranía La Lindosa, on the northern edge of the Colombian Amazon, toward the end of the last ice age, about 12,600 to 11,800 years ago. During that time, "the Amazon was still transforming into the tropical forest we recognize today," Robinson said. Rising temperatures changed the Amazon from a patchwork landscape of savannas, thorny scrub and forest into today's leafy tropical rainforest.

The thousands of ice age paintings include both handprints, geometric designs and a wide array of animals, from the "small" — such as deer, tapirs, alligators, bats, monkeys, turtles, serpents and porcupines — to the "large," including camelids, horses and three-toed hoofed mammals with trunks. Other figures depict humans, hunting scenes and images of people interacting with plants, trees and savannah creatures. And, although there is also ice age animal rock art in Central Brazil, the new findings are more detailed and shed light on what these now-extinct species looked like, the researchers said.

"The paintings give a vivid and exciting glimpse into the lives of these communities," Robinson said. "It is unbelievable to us today to think they lived among, and hunted, giant herbivores, some which were the size of a small car."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Many of South America's large animals went extinct at the end of the last ice age, likely through a combination of human hunting and climate change, the researchers said.

Excavations within the rock shelters revealed that these camps were some of the earliest human-occupied sites in the Amazon. The paintings and camps offer clues about these early hunter-gatherers' diets; for instance, bone and plant remains indicate that the menu included palm and tree fruits, piranhas, alligators, snakes, frogs, rodents such as paca and capybara, and armadillos, the researchers said.

Scientists excavated the rock shelters in 2017 and 2018, following the 2016 peace treaty between the Colombian government and FARC, a rebel guerrilla group. After the peace agreement, researchers spearheaded a project known as LastJourney, which aimed to find out when people first settled the Amazon, and what impact their farming and hunting had on the biodiversity of the region.

"These rock paintings are spectacular evidence of how humans reconstructed the land, and how they hunted, farmed and fished," study co-researcher José Iriarte, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter, said in the statement. "It is likely art was a powerful part of culture and a way for people to connect socially."

The findings were published in April in the journal Quaternary International, and the University of Exeter released a statement today (Nov. 30) to coincide with a new TV documentary on the finding called "Jungle Mystery: Lost Kingdoms of the Amazon," which will air in the U.K. in December.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular