Ice volcanoes on Pluto may still be erupting

More heat under the dwarf planet's surface could even hint at the potential of life.

An area of Pluto that researchers think was formed from the eruption of ice volcanoes is unique on the dwarf planet and in the solar system, a new study suggests.

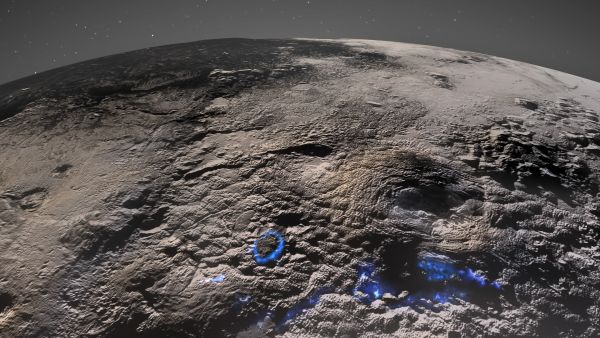

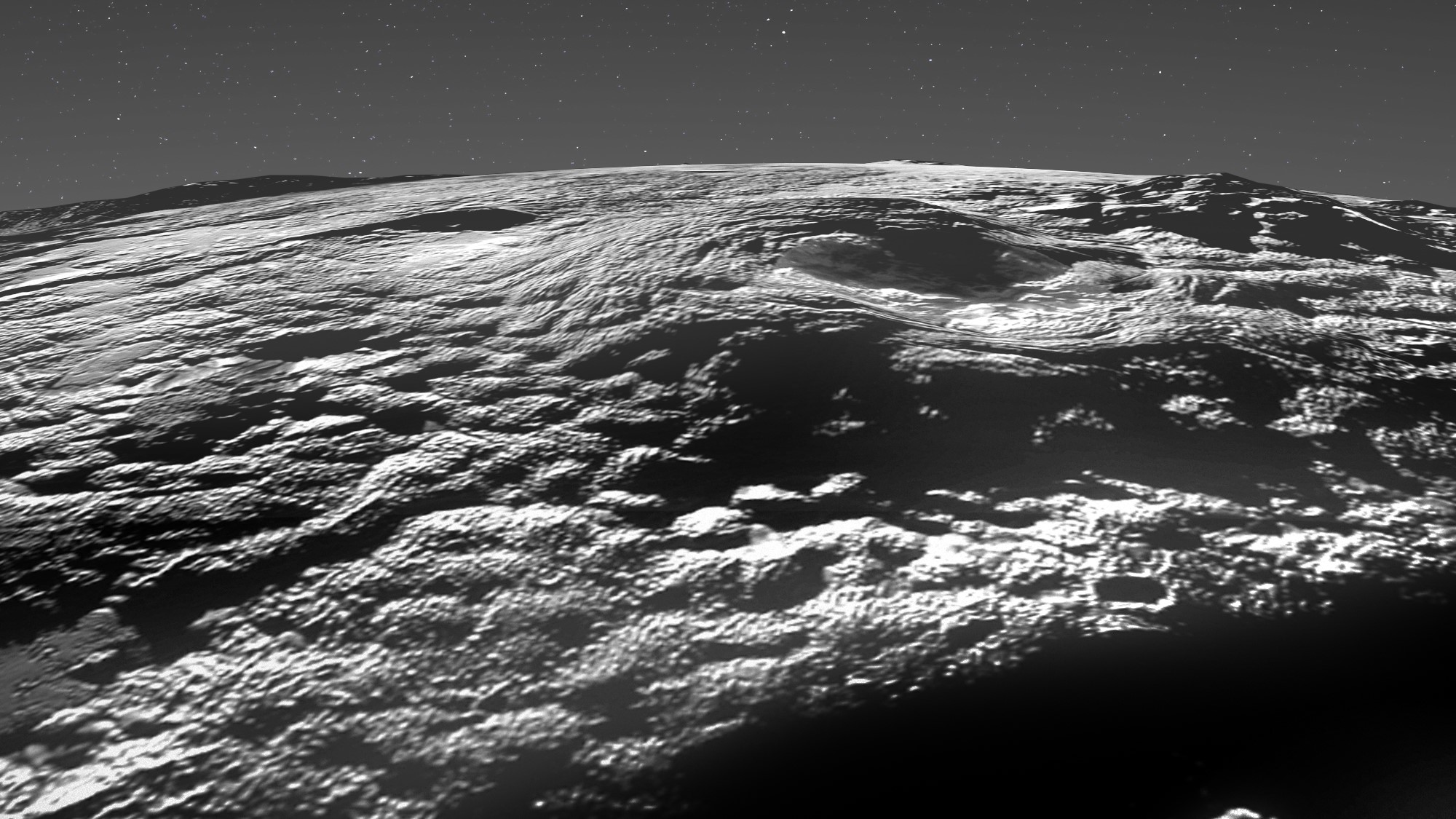

NASA's New Horizons mission, which launched in 2006, took detailed photos of the surface of Pluto, a dwarf planet and the largest object in the Kuiper Belt. Now, a new analysis examines images of an area containing two main mounds that scientists have proposed are ice volcanoes. In the study, the researchers conclude that the surface around these mounds was likely formed by fairly recent activity of the ice volcanoes, or cryovolcanoes.

The finding raises the possibility that these volcanoes may still be active and that liquid water, or something like it, flows or recently flowed under the surface of Pluto. Recent activity also means that there is likely more heat in Pluto's interior than scientists previously thought. Given other recent research, the scientists say their work could even raise the possibility of life existing under Pluto's surface.

Related: 7 solar system worlds where the weather is crazy

The researchers analyzed photographs of a region dominated by two large mounds, called Wright Mons and Piccard Mons, which scientists think are cryovolcanoes. Wright Mons is a mount 2.5 to 3 miles (4 to 5 kilometers) high and about 90 miles (150 km) wide, while Piccard Mons is about 4 miles (7 km) high and 150 miles (250 km) wide.

The suspected ice volcanoes also have extremely deep depressions at their peaks — the one on Wright Mons is about as deep as the mount is high. Many parts of the area also have an unusual, lumpy or "hummocky" appearance, made up of undulating, rounded mounds. The researchers think smaller mounds, formed from ice volcanoes, could have accumulated over time to form these two main mounds.

"There was no other areas on Pluto that look like this region," Kelsi Singer, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado and the lead author of the study, told Space.com. "And it's totally unique in the solar system."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unlike other areas of Pluto, this area has few to no impact craters, indicating that the surface was formed relatively recently in geological time. Based on the lack of craters, the area is likely no older than one or two billion years old, with some areas likely being less than 200 million years old, Singer said.

In some ways, cryovolcanoes are analogous to volcanoes on Earth, since much of Pluto's surface is made of ice, and temperatures on Pluto are far below water's freezing point. That means that liquid water, or something like it which is at least partially fluid or mobile, would be like magma on Earth, coming up to the surface after an eruption and freezing, or hardening, into a solid.

"It's probably not coming up completely liquid — it's probably more like a slushy thing where you have some liquid and some ice, or it could even be more like a flowing solid," Singer said, which could be "more like ketchup or silly putty." It could even be more solid ice that can still flow.

"We all know that ice can flow because we have glaciers that flow on Earth," she said.

Though scientists don't totally understand how cryovolcanic activity on Pluto might work, it is likely powered by radiogenic heat created by the decay of radioactive elements in the dwarf planet's interior. A similar phenomenon is also one of the sources of heat in the Earth's interior, although Pluto does not have plate tectonics, the complex system of shifting continental crust that underlies geologic activity on Earth. Scientists call geologic activity like that on Pluto "general tectonics," which can still create features like faults in rock but does not have tectonic plates.

Pluto's cryovolcanoes display some similarities to shield volcanoes on Earth, which are low-profile volcanoes which form from the steady accumulation of lava flows into rounded structures. (Think of the Hawaiian island volcanoes, rather than an eruption like Mount Saint Helens or Vesuvius.) But shield volcanoes usually form from very liquid lava, unlike what scientists think happened on Pluto.

Some volcanoes on Earth and other planets also have a depression in their middle called a caldera, formed when a newly erupted volcano collapses into the void left by all the material it spewed out. But the depression on Wright Mons is so deep that the volcano would have had to lose about half of its volume to be similar in shape to Mauna Loa, a shield volcano in Hawaii that is one of the largest volcanoes on Earth and has a comparatively small caldera, though the two structures are similar in volume, Singer said.

There's still a lot researchers don't know about these features, how they were formed, and how cryovolcanism works on Pluto. The idea that liquid water could exist beneath the surface of Pluto raises the chances of life existing on Pluto from practically non-existent to slightly more plausible, given other research suggesting that Pluto was hot when it first formed and could still have a liquid ocean under its icy surface.

"I think that it is a little more promising, and that there might be some heat and liquid, potentially liquid water closer to the surface," Singer said. "But there's still some big challenges for poor microbes that want to live on Pluto."

The research is described in a paper published Tuesday (March 29) in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Rebecca Sohn is a freelance science writer. She writes about a variety of science, health and environmental topics, and is particularly interested in how science impacts people's lives. She has been an intern at CalMatters and STAT, as well as a science fellow at Mashable. Rebecca, a native of the Boston area, studied English literature and minored in music at Skidmore College in Upstate New York and later studied science journalism at New York University.