Sacrificed llama mummies unearthed in Peru

The llamas were adorned with earrings and necklaces.

Archaeologists in Peru have found the naturally mummified remains of five llamas that were sacrificed to the Incan gods about 500 years ago.

The mummified llamas are still adorned with the colorful strings, red paint and feathers that the Inca decorated them with before sending them to their deaths, likely by burying these animals alive.

The finding is so rare, that even though archaeologists have been excavating the remains of the Inca Empire (also spelled Inka) along the Pacific Coast of South America for more than a century, "none of them have found anything like this," study lead researcher Lidio Valdez, an adjunct assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology at the University of Calgary in Canada, told Live Science.

Related: Image gallery: Inca child mummies

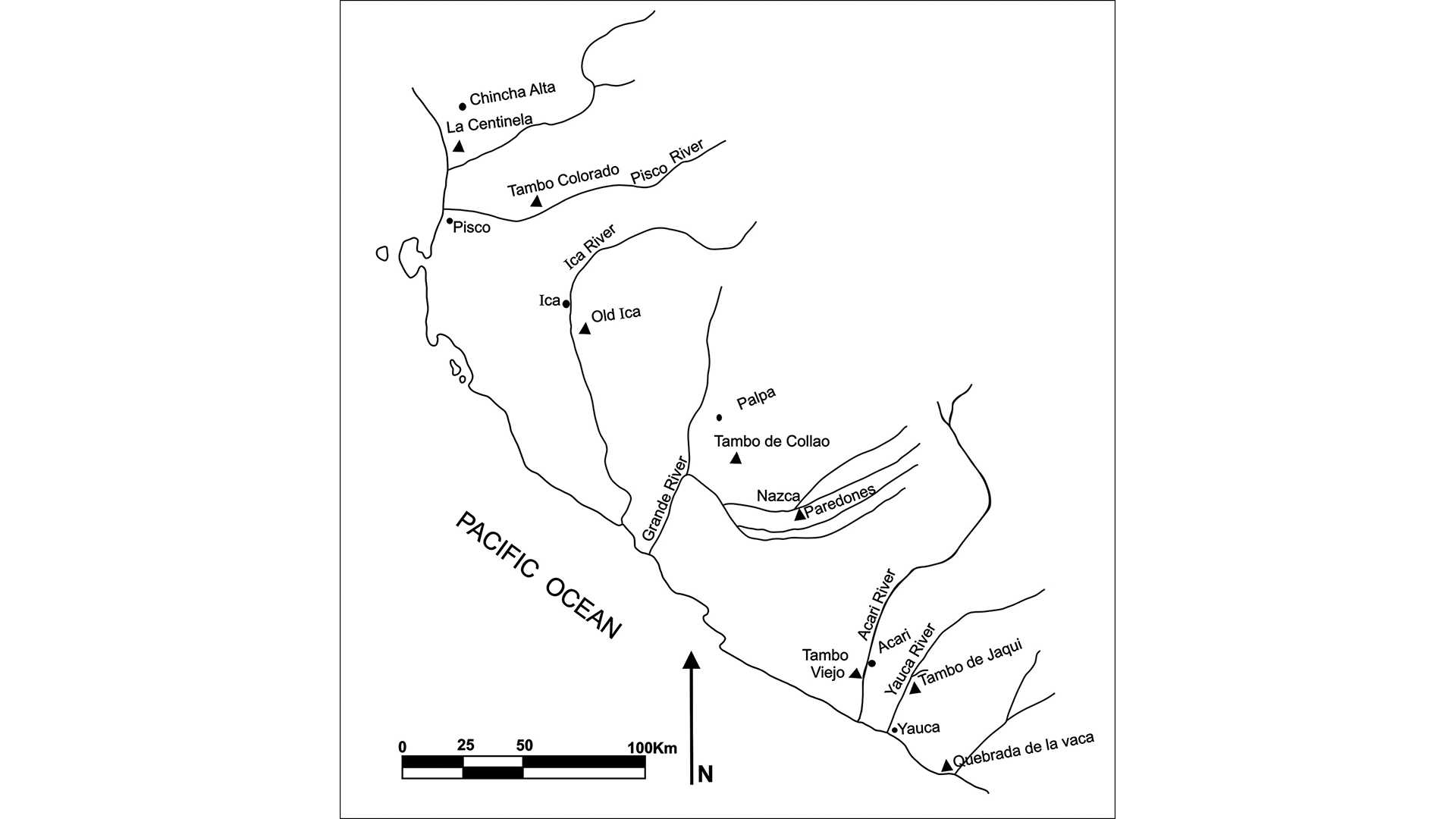

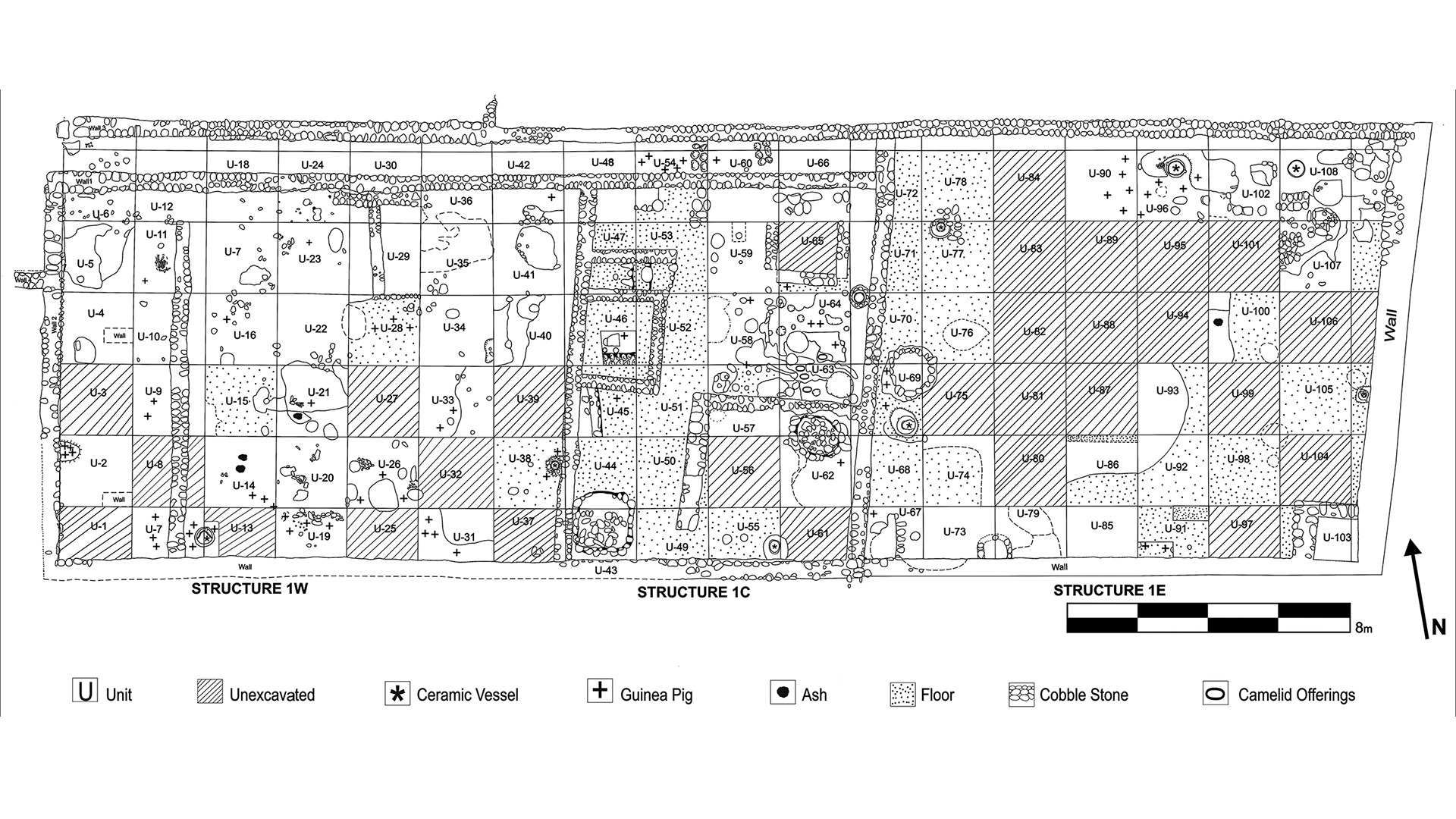

Valdez and his colleagues found the mummified llamas (Lama glama) at Tambo Viejo, an archaeological site on the Pacific coast of Peru, in 2018. The archaeologists discovered the llama mummies buried beneath clay floors in two of the several buildings that surround the two plazas at the site. Four llamas — one brown and three white — were buried together in one building, and a single brown llama was found beneath the floor in the other building, Valdez said.

"In the first case, it appears that there were more llamas, but looters have disturbed the original context," Valdez said. "The llamas had been buried facing east," likely because the sun, which rises in the east, was a major Inca deity, he noted.

These sacrifices not only honored the gods, which the Inca associated with successful harvests, healthy herds and war victories, but also may have made the Inca Empire popular among the local culture, because the sacrifices came along with a huge feast.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Colorful decorations

The young llamas were richly decorated; long string tassels dyed red, yellow, green and purple were attached to the llamas' ears. These strings, made of camelid fiber, were "attached to the ears just for the occasion," Valdez said. The camels also wore necklaces of colored strings around their necks.

"The adornments suggest that the offerings were very special," Valdez said. "Indeed, historical records indicate that brown llamas were sacrificed to the creator Viracocha, while white llamas to the sun, the Inka main deity."

Some of the llamas had painted faces. The three white llamas had a red dot on top of their heads and a red line descending from each eye toward the nose, the researchers wrote in the study. Moreover, one of the white llamas was buried with a guinea pig (Cavia porcellus), and all three white llamas were buried with the feathers of a tropical bird attached to 4-inch-long (10 centimeters) sticks. The three white llamas were also buried near pits filled with maize cobs, lima beans and guinea pigs, as well as a package of ash (known as lime) associated with the chewing of coca, a leaf considered sacred by the Inca; it's also the raw ingredient used to make cocaine.

After the llamas were decorated, their limbs were bent under their bodies and tied with long ropes, also made from camelid fibers. The archaeologists couldn't find any cut marks on the throats or diaphragms of these llamas, so it's possible they were buried alive. "If [this idea is] correct, this practice would parallel the evidence for the burial of living human sacrifices," the researchers wrote in the study.

Related: The 25 most mysterious archaeological finds on Earth

Archaeologists have found other Inca sites containing animal and human sacrifices, but the newfound discovery is one of the best preserved, said Susan deFrance, a professor of anthropology at the University of Florida, who wasn't involved in the new study. Other sacrificial findings are not as "complete, not as beautiful as this, where you can tell the coat color and all the material that's with it," she told Live Science. "So, this is fairly rare."

Sacrifice and feast

The archaeologists found a large earthen oven in another building near the llama sacrifices. "Its presence suggests that ritual celebrations culminated in the sharing of food in the form of feasts," the researchers wrote in the study.

Perhaps, this animal sacrifice had a larger purpose; it may have helped maintain the Inca's power over their empire, Valdez said. Nine separate radiocarbon dates indicate that these llamas were sacrificed in about 1500, or near the end of the Inca occupation of the site at Tambo Viejo. A few decades before, the empire had peacefully incorporated the southern Peruvian coast into its territory. Then, the Inca built an administrative center at Tambo Viejo, according to Spanish documents from Columbian times.

"The Inka did not just go to Tambo Viejo to make animal sacrifices; instead, the sacrifices were part of much larger celebrations that included sharing food and drinks, all sponsored by the state," Valdez said. Ultimately, food sharing was a good strategy that enabled the Inka to cement lasting political alliances and reciprocal relationships with the newly conquered peoples," Valdez said.

The llamas aren't the only major animal sacrifice at Tambo Viejo. Earlier research there by Valdez revealed the discovery of several dozens of sacrificed guinea pigs that were also adorned with colorful string earrings and necklaces, according to a 2019 study in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. Early Spaniards in South America noted that the Inca sacrificed these animals by the hundreds, but this is some of the first direct evidence that that it really happened, Valdez said.

The study was published online Thursday (Oct. 22) in the journal Antiquity.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.