Incan Empire's 'Reign of Terror' Revealed in Four Ancient Skulls Found in Trash Heap

The skulls were strung up in a terrifying display of power.

Something was amiss at the ruins of Iglesia Colorada, an ancient Incan village in the foothills of the Andes. In the remains of what had been a garbage dump, among ancient food scraps and shards of discarded pottery, researchers discovered four skulls. No bodies, no formal burial, no jewelry to carry on to an afterlife — just the skulls. No one knew why they were there.

For over 15 years, since the skulls were uncovered in 2003, the mystery has baffled archaeologists. But two researchers at the National Museum of Natural History in Santiago, Chile, have proposed an explanation: The skulls paint a picture of an Incan reign of terror, in which the heads of four villagers were put on display as a warning to inhabitants.

The period from the late 1400s to the early 1500s was a tumultuous time for much of South America. During these years, the Incan empire was slowly expanding its reach across the Andes. While civilizations had long existed in the valleys of the Andes, they were mostly isolated, said study co-author Francisco Garrido, the curator of archaeology at the National Museum of Natural History. While some of these places probably joined the empire without much resistance, others weren't so amenable, he added.

Related: Images: The Mummy of a Murdered Incan Woman

"They really didn't buy the idea of incorporating to an Incan empire," Garrido told Live Science.

That was probably the case in the town of Iglesia Colorada, Garrido and his co-author, Catalina Morales, argue in a new study in the August 2019 issue of the journal Latin American Antiquity. And based on the mysterious skulls in the rubbish heap, which date back to this period of Incan expansion, conquerors resorted to violence to terrify villagers into submission, the study authors suggest.

From the beginning, archaeologists knew the rubbish heap was no typical grave. The same village had a known burial site, a well-organized network of circular graves protected by logs, in which the remains of whole bodies (no decapitated skeletons) were found surrounded by pottery and jewelry.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

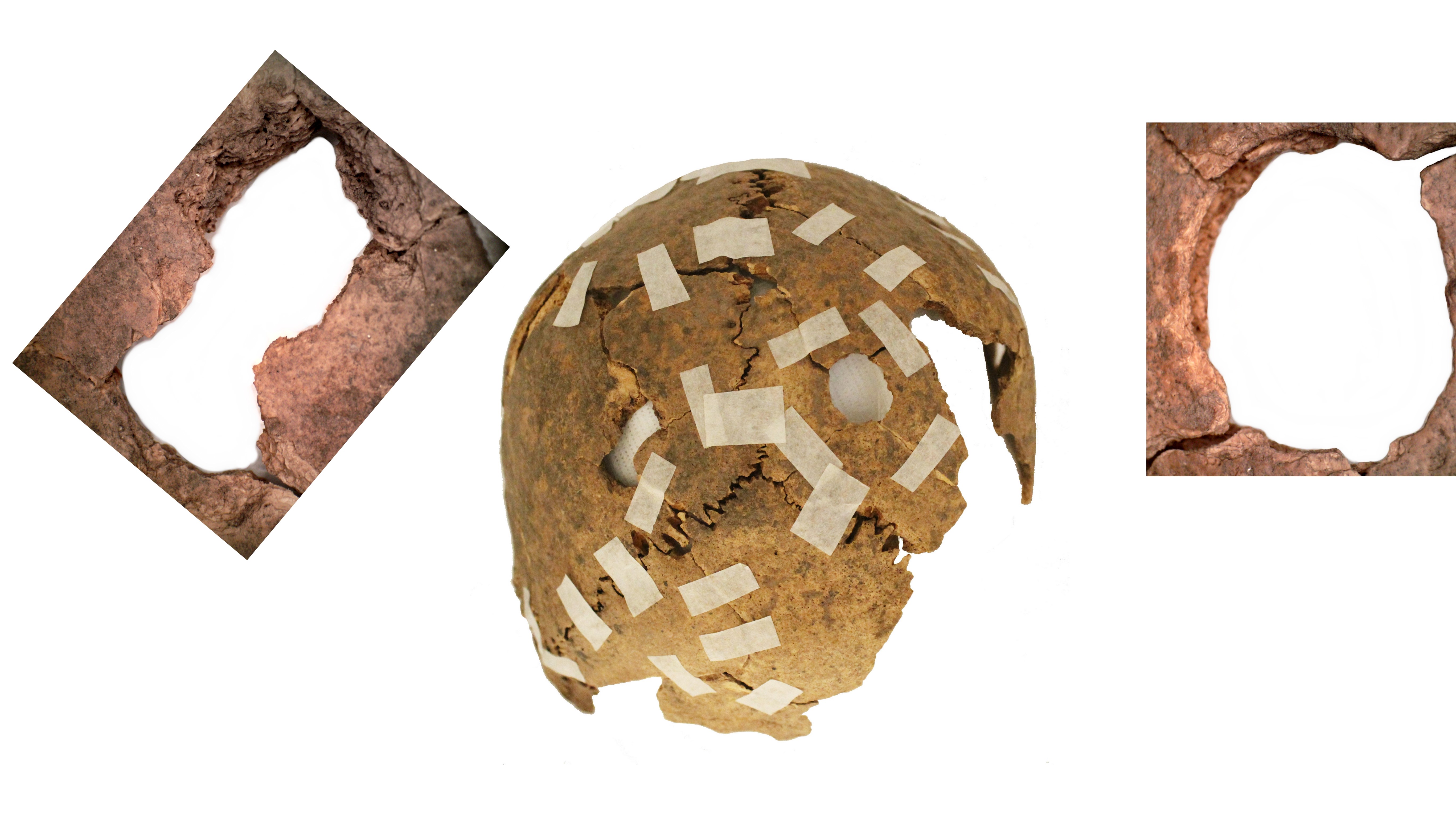

The seemingly haphazard way in which these skulls were discarded isn't the only piece of evidence that points to these victims' violent end. All the skulls share similar markings: drilled holes and strange marks around the jaws, as though the heads had been scraped. The holes suggest that the skulls were strung up on rope, so that everyone in the village could see the warning, Garrido said. The scrape marks indicate that the jaws were skinned before the heads were put on display — presumably for the shock value, he added.

Three of the skulls belonged to young women and one belonged to a child. Based on the density of the bone, all the victims were malnourished.

"It doesn't seem that the Incas targeted the leaders [of the village]," Garrido explained. That's because healthy young males would have been profitable for their empire — as laborers, warriors or as a source of tax revenue.

But this reign of terror wasn't widespread across the empire, Garrido points out. "It wasn't a killing spree," he said.

Instead, the shocking display was specific to this town. Not only was the village most likely rebellious — it might have posed a logistical challenge to the Incan empire, Garrido said. Iglesia Colorada was both far from the hub of Cuzco and tucked in the driest region of the world, the Atacama desert. Unable to send government resources so far from their capital city and with little knowledge of the extreme terrain, the Incan empire would have faced difficulties governing the town. Rebellious locals, with specialized knowledge of how to survive in the harsh environment, would have had the upper hand over the invaders, Garrido added. In order to demonstrate power and control (and perhaps instill a lasting sense of fear) the Incas may have resorted to extreme measures — like stringing trophy skulls for an entire village to see, Garrido said.

His analysis is the first published research about the skulls.

- 25 Cultures That Practiced Human Sacrifice | Live Science

- Image Gallery: Inca Child Mummies

- 25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries

Originally published on Live Science.

Isobel Whitcomb is a contributing writer for Live Science who covers the environment, animals and health. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fatherly, Atlas Obscura, Hakai Magazine and Scholastic's Science World Magazine. Isobel's roots are in science. She studied biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, while working in two different labs and completing a fellowship at Crater Lake National Park. She completed her master's degree in journalism at NYU's Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon.