How surgery in infancy led to a woman's stone 60 years later

Surgery for a rare gut problem in infancy caused this woman to develop a calcified stone decades later.

Bowel surgery given to a 6-day-old infant had unusual ramifications for her decades later when she was 60 years old, according to a new case report.

At first, emergency room doctors were unsure why the 60-year-old woman was vomiting and having abdominal pains. But they cracked the case after learning that she had been treated for a rare condition as a baby: jejunal atresia, which means that she had been born with a blockage in her intestines.

Although surgeons fixed the blockage in her infancy, their surgical method led the woman to develop a large and painful calcified stone in her intestine years later, which is what caused her symptoms the day she went to the emergency room, according to the case report, which was published on Jan. 8 in the journal BMJ Case Reports .

Related: 27 Oddest Medical Case Reports

Babies with jejunal atresia can't digest food without it getting stuck at the blockage point, meaning that nutrients can't make their way down the intestinal tract. These blockages form while the baby is still in the womb. During development, the small intestine (the jejunum) doesn't properly attach to the abdominal wall, which, in turn, causes part of the small intestine "to twist around an artery that supplies blood to the colon," according to the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Without a proper blood supply, that part of the bowel shrinks until it is completely blocked, said Dr. Shant Shekherdimian, an assistant professor of pediatric surgeon at the University of California, Los Angeles, who wasn't involved with the case report.

Babies with jejunal atresia often vomit bile, have swollen abdomens and can't poop. Surgery, however, can help; doctors can remove the blockage and reconnect the intestine to form a continuous tract, Shekherdimian said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One reconnection method involves joining the intestine's two open ends together. In the woman's case, doctors did a side-to-side surgery, in which they laid out the intestines in two straight lines and reconnected them at a central, overlapping point.

Unbeknown to the woman, this type of surgery can lead to complications, "because a part of that overlap is redundant," Shekherdimian told Live Science. "It's just kind of sitting there. And also, because the bowel has been cut and reconnected, it doesn't really have the normal nerves and the ability to push like the normal bowel does."

Over the years, pieces of food and other substances in the intestines got stuck in that overlap, which grew into a pouch.

In other words, the woman had a dormant piece of intestine that was collecting bits and pieces that it couldn't push out. However, this piece of bowel did one job well: It absorbed fluids. Those fluids are then squeezed out of the intestinal wall through the normal digestive process. "As this stuff sits there and gets the fluids sucked out of it," Shekherdimian said, "then, you can start developing stones or things that look like stones."

On top of that, this useless piece of intestine can cause problems for neighboring regions of intestine, because "it's just a big boggy thing that's sitting on the rest of the intestines that are working," Shekherdimian said. "Now they have this heavy thing sitting on them, which is now causing another blockage. And that's probably what happened [to this woman] 60 years later."

Related: The 9 Most Interesting Transplants

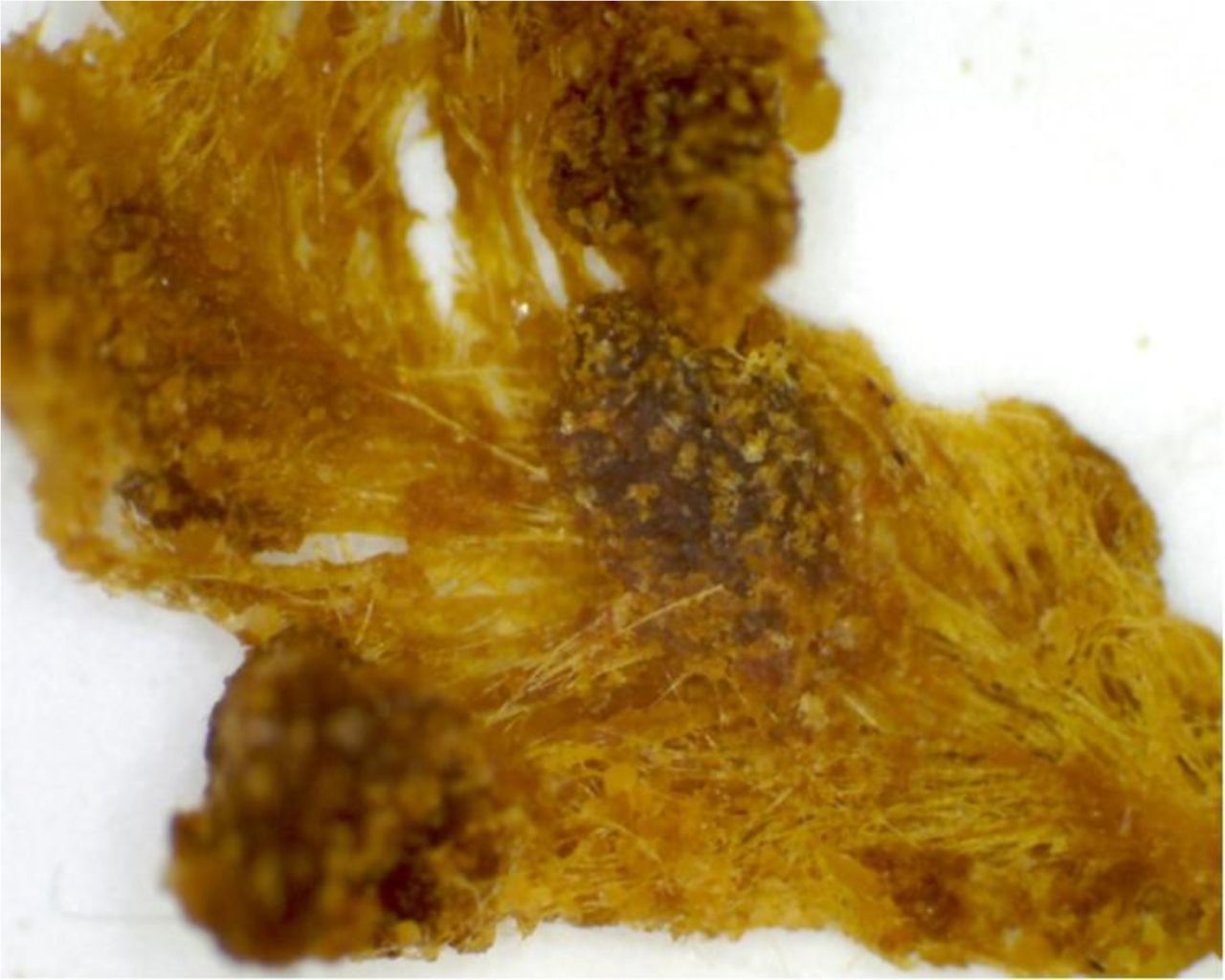

After arriving at the ER, the woman received a CT scan, which revealed the blockage. During a surgery to remove the troublesome tissue, doctors removed a calcified stone from her intestine that was 1.5 by 1.3 inches (4 by 3.5 centimeters).

"To our knowledge, this is the first case report of intestinal obstruction with formation of a large stone 60 years after repair of duodenal [the first part of the small intestine] atresia," the authors wrote in the case report. The woman made a full recovery, they added.

There are two important lessons that can be learned from this woman's experience, Shekherdimian said. First, patients often see operations such as this one as permanent fixes, "and many times they're not," he said. "I think this case highlights the importance of close follow-up and evaluation."

Moreover, "it is important to try to minimize the amount of non-functional intestinal tissue that [surgeons] leave behind," Shekherdimian said, "because we as pediatric surgeons see this complication frequently. "

- Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick

- 8 Awful Parasite Infections That Will Make Your Skin Crawl

- 7 Ways to Stay Healthy After 40

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.