Anal bulbs, detachable butt hairs and booty camouflage: Welcome to #InverteButtWeek on Twitter

Bubbles, probes and pores are just the tip of the invertebutt iceberg.

Sometimes the best view of an insect, spider, crab or clam is the sight of its rear end.

Animal butts come in a mind-bending variety of shapes and sizes, and the butts of invertebrates — animals without backbones — are especially diverse and often delightfully weird. From marine worms with hundreds of butts to moths with long, pulsing butt appendages, many invertebrates possess truly bizarre posterior structures or use their behinds in ways that are unthinkable (or perhaps enviable) for humans.

So it's no wonder that these bountiful bottoms inspired a group of artists and science communicators to launch #InverteButtWeek on Twitter from March 1 to March 8, inviting all to partake in a celebration of marvelous invertebrate butts. But be prepared: anal bulbs, flaps, bubbles, probes, pores and chimneys are just the tip of the invertebutt iceberg.

Related: The 12 weirdest animal discoveries

On Twitter, images of invertebrate butt diversity abounded in photos, footage and artwork. YouTube science program SciShow tweeted about simple aquatic animals called bryozoans that have simply wonderful retractable anuses. Nature photographer Jen Cross tweeted an image of an American pelecinid wasp's "long booty," which probes into soil for grubs. And marine biologist Christopher Mah, a researcher at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, tweeted a photo of a colorful sea urchin in the Astropyga genus demonstrating an anal bulb expulsion — dispelling waste pellets from its body inside a transparent sac.

There were also tweets highlighting colorful spider butts, pollen-dusted bee butts, the iridescent, detachable butt hairs of planthopper nymphs and even fossilized butts such as the long anal tube of a crinoid, a filter-feeding marine animal.

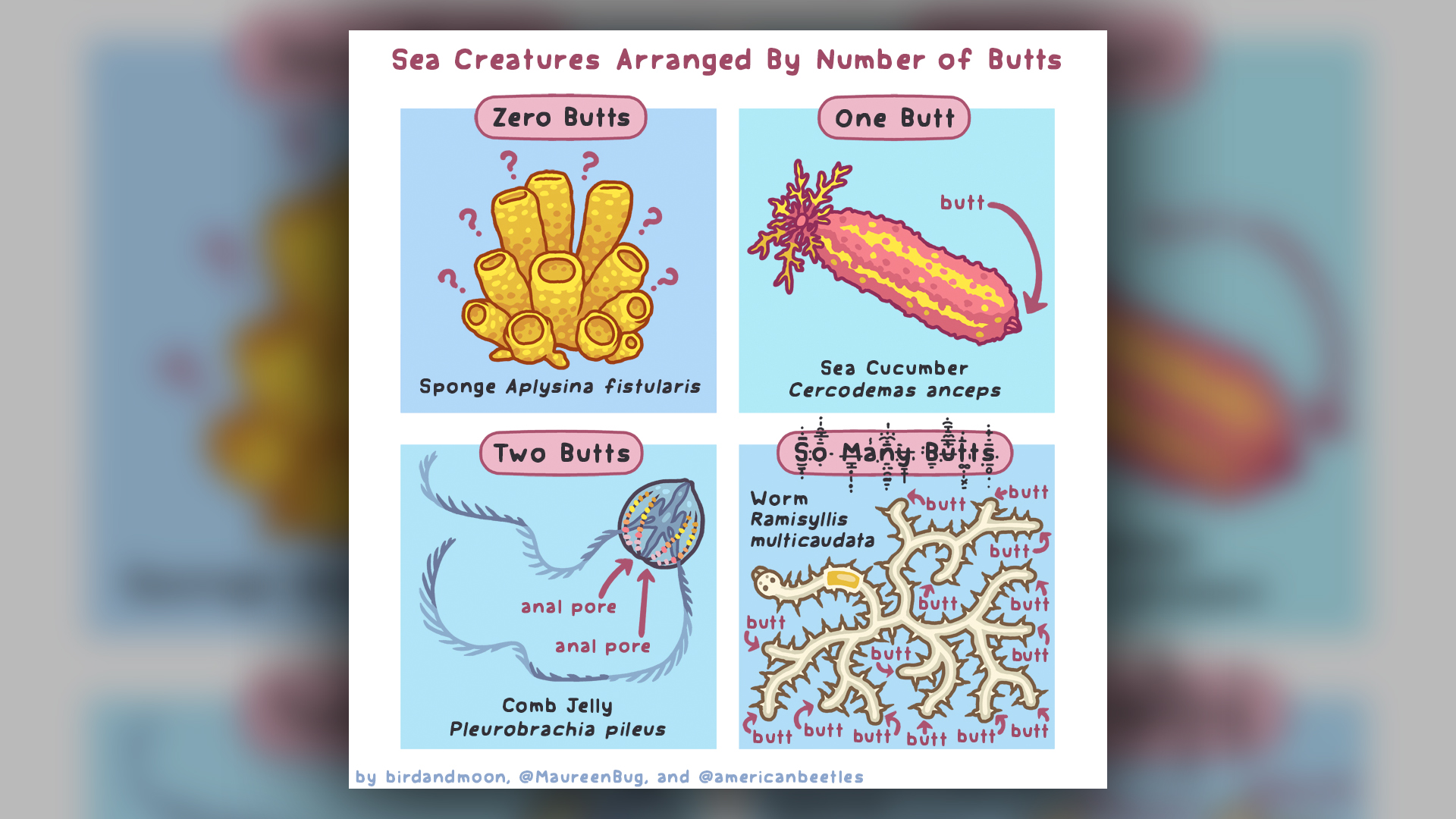

Cartoonist and writer Rosemary Mosco, one of InverteButtWeek's co-creators, shared a comic about a beetle that poses as an ant's butt. Another of Mosco's comics, created in collaboration with microbial biologist Maureen Berg and Ainsley Seago, a curator of Invertebrate Zoology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, celebrated "the beautiful butts of the sea," Mosco wrote in a tweet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Focusing on invertebrate butts is a cheeky way to share facts about the complex lives of creatures we tend to loathe or ignore," Mosco told Live Science in an email. "Invertebrates are endlessly fascinating, and butts are a fine gateway into this wonderful world."

The seeds for #InverteButtWeek were planted in January, co-organizer and freelance illustrator Franz Anthony told Live Science in an email. That's when Maite Aguado, a marine biologist and a professor at the Georg-August-Universität Göttingen in Germany, tweeted on Jan. 19 about the branching worm Ramisyllis kingghidorahi, which Aguado and her co-authors had recently described in the journal Organisms Diversity & Evolution.

The sight of this many-butted worm provoked conversations about the number of butts that animals can have — "they seem to go from zero, usually one, sometimes two, and then suddenly a bajillion," Anthony said. That in turn led to the creation of a group chat among artists and illustrators who appreciated butt jokes, and the plan to invoke the power of the internet to celebrate the wonderful world of invertebrate butts grew from there.

"We originally wanted to talk about animal butts in general, but decided to focus on invertebrates," Anthony explained. "Invertebrate bodies are so different from ours, even the definition of what a butt is becomes a philosophical question — is it the exit hole, the rump surrounding the hole, or simply the rear end of the animal? Even defining the 'rear' is a challenge in invertebrates, many animals like clams or corals don't have a face or walk forwards," he said. Anthony explored this quandary in the graphic "What is a butt?" which he tweeted on March 1.

With the powers of @spissatella & @RosieRiots's science by my side, we present:The Butt Political Spectrum ™What is A Butt? How do you even define a butt?Tag yourself I'm Butt Chaotic#InverteButtWeek pic.twitter.com/inLEU9ODWVMarch 1, 2022

"I hope that this hashtag brings people some joy in these weird times," Anthony said. "And I hope that people learn to appreciate the weird and forgotten sides of nature, not just the fuzzy friends and flashy flowers we see on a daily basis."

For everyone who appreciates invertebrate butts, that enjoyment doesn't have to end after #InverteButtWeek is over. As biologist and photographer Klaus Stiefel tweeted on March 2, when he shared footage of a butt-breathing sea cucumber, "It's always #invertebuttweek in front of my lens."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.