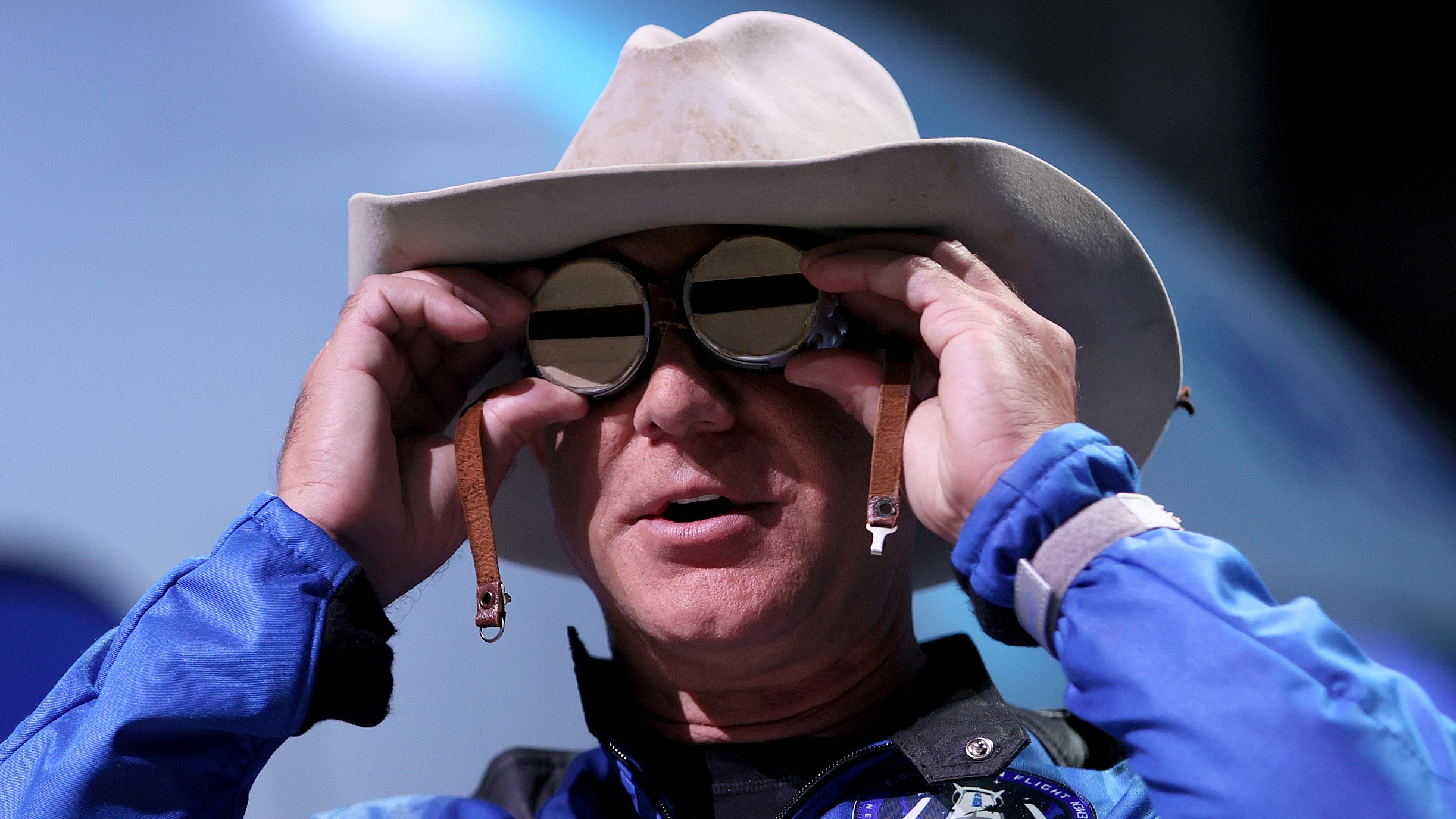

Jeff Bezos went to the edge of space. Does that make him an astronaut?

The former Amazon CEO took only 14 hours of flight training.

Now that Jeff Bezos has reached the edge of space, does that mean the world's richest man is an astronaut?

The claim, made by the spaceflight company belonging to the former CEO of Amazon, has been met with skepticism by some experts.

"Our astronauts have completed training and are a go for launch," Blue Origin, the suborbital spaceflight company owned by Bezos, announced on Twitter yesterday evening (July 19). Less than 10 hours later, at 9:22 a.m. EDT, Bezos and three other passengers — Mary "Wally" Funk, an 82-year-old aviator; Oliver Daemen, an 18-year-old son of a Dutch hedge fund CEO; and Bezos' brother Mark — finished their successful, slightly more than 10-minute flight by touching down in a puff of dust not far from the New Shepard rocket's launch site in West Texas, Live Science reported.

Related: Photos: Blue Origin's New Shepard mission to space

At the highest point of its ascent, Bezos' passenger capsule crossed the Kármán line, the boundary 62 miles (100 kilometers) above sea level that some scientists use to demarcate where Earth's atmosphere ends and outer space begins.

It could seem like an open and shut case, then: The richest man on the planet went to outer space, so he must be an astronaut. But it takes more than the crossing of a boundary to earn the title, space experts said.

"'Training'" Scott Manley, a space commentator, tweeted as a reply to Blue Origin. "Remember Wally [Funk] has more flight experience than any astronaut in space right now." Funk has logged 19,600 flight hours on a variety of aircraft and has taught more than 3,000 people to fly.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Funk, who prepared to be an astronaut as part of the 1961 Mercury 13 program but was excluded from spaceflight by NASA because of her gender, is the only member of the crew with any flight training.

Usually, to qualify as an applicant for a NASA training program, astronauts must have a master's degree in a STEM field and either two years of relevant professional experience or 1,000 hours of logged pilot-in-command time on a jet aircraft. After meeting this first requirement, they must pass a strenuous physical evaluation before embarking on a two-year-long basic training course, in which they learn everything from how to pilot a spacecraft to how to communicate in Russian with the Russian Mission Control Center, according to NASA.

Once they have passed basic training, NASA astronauts are assessed for suitability before being assigned to a mission, which they may take up to several years to prepare for before ever taking flight. International Space Station crews tend to train for two years in order to spend six months in space.

In 2017, more than 18,000 people applied to NASA's astronaut class of 2017, but only 12 were selected for further training.

Related: What does it take to become an astronaut?

In contrast, Bezos and his crew received just 14 hours of training over two days before they blasted off, during which they were prepared for nominal, "off nominal" and emergency procedures inside the passenger capsule, Blue Origin lead flight director Steve Lanius said during a July 18 news conference.

Aside from Funk's prior experience, these 14 hours constituted the only training the crewmembers received.

Charles Bolden, a former NASA administrator and astronaut, said that to be considered astronauts, candidates must be prepared to fly the vehicle and work in emergency situations — tasks that the New Shepard, as an autonomous craft, is designed to prevent its passengers from performing.

"When you talk about tourism, you want to try to take the interaction of the human out of the play as much as you can, so you can have a tourist," Charles Bolden, a former NASA administrator and astronaut, told CBS News before the launch. "I was surprised that they were walking up the steps. The most stressful thing they will do today, physically, is get in the vehicle."

The blurring of the definition of "astronaut" to include a trained professional, a space tourist or really anyone who happens to be momentarily floating above our heads could become a more frequent focus for linguistic debate in the future, as more and more tourists embark on suborbital flights.

NASA's official definition is hardly helpful at settling the score; it refers to an astronaut as both a crewmember aboard a spacecraft and someone who makes "space sailing" — which derives from the Greek word for astronaut — their profession.

And then there's the debate about where space begins. Some people say it starts at the Kármán line, where the atmosphere becomes too thin to sustain a normal aircraft in flight. Others contend that the line may be as far up as 93 miles (150 km). By one definition, Bezos could be an astronaut. By the other, he isn't even a space tourist.

"I am reasonably certain there is no single compelling definition for 'the edge of space,'" Edwin Turner, professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University, told Business Insider.

Turner says that a popular definition of space should be the lowest altitude a craft can complete one orbit of the Earth at (without needing to boost itself) before it is slowed by atmospheric friction and dragged back to Earth.

This may mean that an aircraft of one size or shape could arrive in space earlier than another, or that the line may be shifted by changes to the atmosphere, he added.

Perhaps going by definitions alone is unhelpful. After his brief suborbital joyride, the best way to consider whether ‘astronaut’ belongs on the Amazon CEO’s CV might be to ask whether he is now qualified to work as one. If that answer is a no, the job, and the title, should probably be left to the pros.

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.