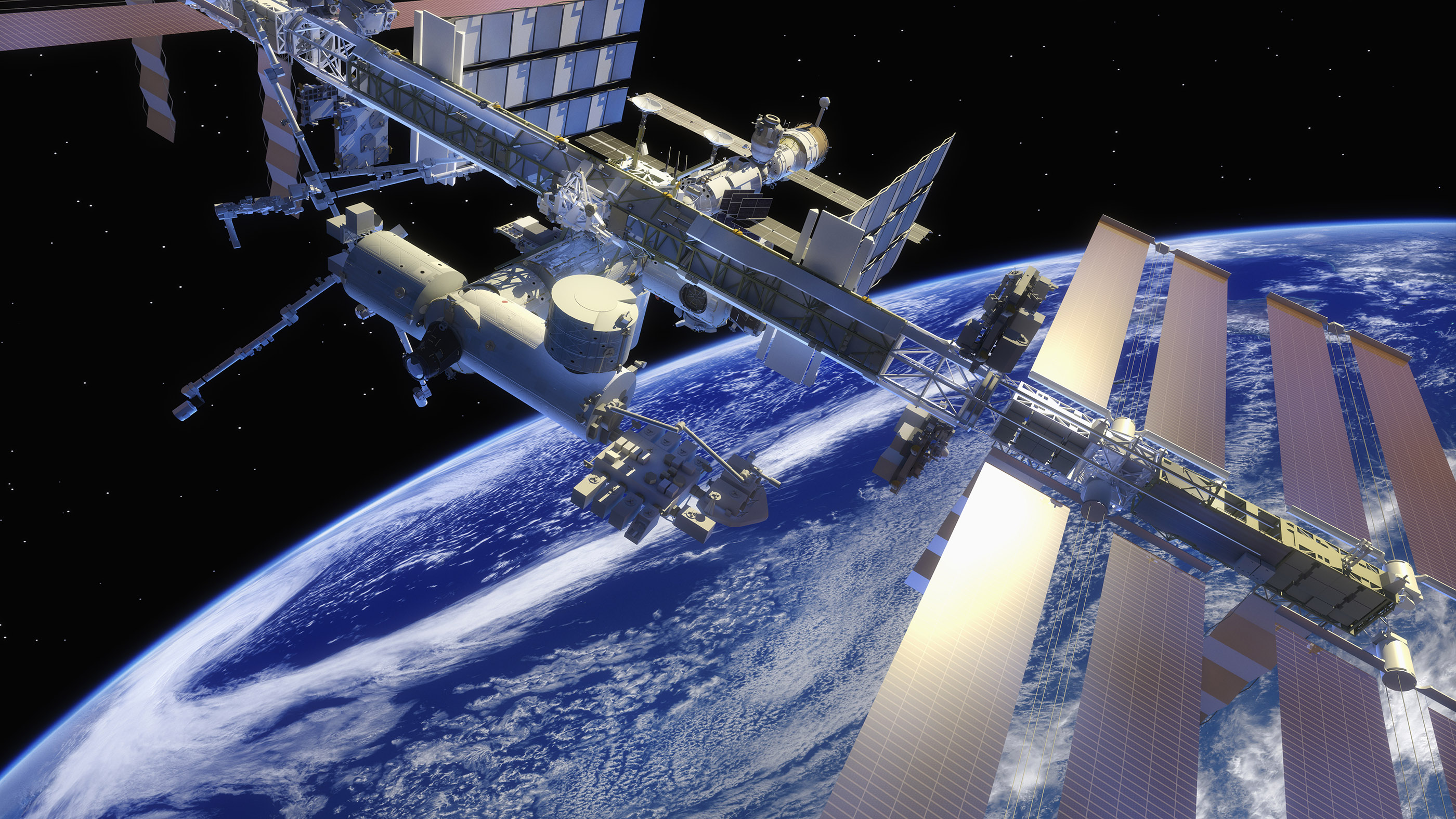

Russia's missile test could have easily obliterated the International Space Station

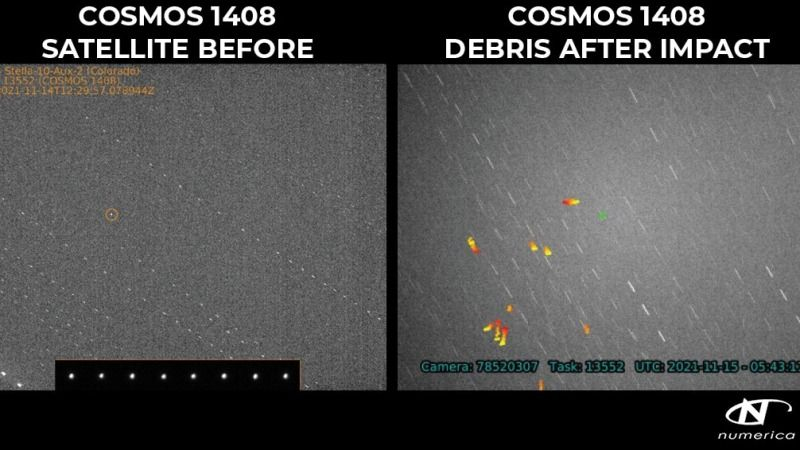

A Russian missile test blasted a Kosmos spy satellite into more than 1,500 pieces of space debris.

In the wee morning hours of Tuesday (Nov. 16), the seven-person crew of the International Space Station (ISS) awoke in alarm. A Russian missile test had just blasted a decommissioned Kosmos spy satellite into more than 1,500 pieces of space debris — some of which were close enough to the ISS to warrant emergency collision preparations.

The four Americans, one German and two Russian cosmonauts aboard the station were told to shelter in the transport capsules that brought them to the ISS, while the station passed by the debris cloud several times over the following hours, according to NASA.

Ultimately, Tuesday ended without any reported damage or injury aboard the ISS, but the crew's precautions — and the NASA administrator's stern response to Russia — were far from an overreaction. Space debris like the kind created in the Kosmos break-up can travel at more than 17,500 mph (28,000 km/h), NASA says — and even a scrap of metal the size of a pea can become a potentially deadly missile in low-Earth orbit. (For comparison, a typical bullet discharged from an AR-15 rifle travels at just over 2,200 mph, or 3,500 km/h).

Related: See stunning images of Russia from space

"It doesn't take a very large hole to basically explode the space station," John Crassidis, a SUNY Distinguished Professor at the University at Buffalo in New York who works with NASA to monitor space debris, told Live Science.

Indeed, a hole measuring just 0.5 inches (1.3 centimeters) wide could cause irreparable structural damage that could completely "wipe out the space station," Crassidis said.

This is a huge concern as the amount of orbital debris — or "space junk" — around Earth has grown at an exponential rate over the past 60 years, Crassidis said. NASA currently tracks more than 27,000 pieces of orbital debris that measure larger than a softball, and uses computer models to estimate the positions of millions of smaller pieces of junk that are too tiny to be seen.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If a piece of space debris has anything greater than a 1 in 10,000 chance of hitting a passing satellite or spacecraft, NASA employs avoidance maneuvers to physically move the jeopardized craft out of harm's way, Crassidis said. This is a tricky balancing act, he added, as moving a satellite out of the path of one piece of debris could unintentionally send it into the path of a different piece of debris — such is the scale of the clutter up there.

Since 1999, the ISS has changed course 25 times to avoid known debris. To protect the station from smaller, unknown pieces of clutter, the craft is covered in more than 100 impact shields known as Whipple Shields, which serve as "sacrificial bumpers" to take incoming hits instead of the ISS wall, according to NASA.

Multiple dents and dings on the ISS exterior show that the station has been hit with debris before; in June 2021, a piece of debris even plowed a hole into one of the station's robotic arms — a metal apparatus with a diameter of just 14 inches (35 cm). Luckily, it inflicted very little damage and the arm resumed operations immediately.

However, where the ISS itself is well protected from incoming projectiles, the astronauts who crew and maintain it are not — and that is where the biggest risk lies. According to Crassidis, even an encounter with the smallest piece of orbital debris could instantly kill an astronaut working on the outside of the ISS during a space-walk.

"Space suits are not protected at all," Crassidis said. "Imagine a marble going 17,000 miles per hour [27,000 km/h] at you — it would go right through you, like a bullet."

Unfortunately, Crassidis added, there are no international laws preventing nations from conducting low-orbit missile tests like the one Russia just did. He fears that it may take an astronaut getting seriously injured or even killed before the world takes the space junk problem seriously.

While the immediate danger to the ISS from Russia's missile test has passed for now, the debris from the blast could remain a hazard for years or even decades to come, Tim Flohrer, head of the European Space Agency's (ESA) Space Debris Office, told Live Science's sister site Space.com. Satellites will almost certainly have to take avoidance actions to steer clear of the junk cloud, and the ISS continues to pass near it every 90 minutes.

NASA will monitor the debris cloud as closely as possible. For the ISS to be critically impacted by a tiny, un-trackable piece of the satellite would be like winning an "unlucky lottery," Crassidis said — unlikely, but not impossible.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.