James Webb Telescope spots galaxies from the dawn of time that are so massive they 'shouldn't exist'

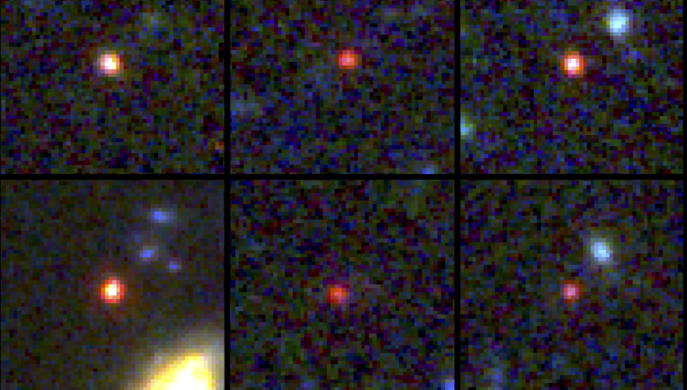

The James Webb Space Telescope spotted six gigantic galaxies, each roughly the size of our own Milky Way, that formed at a bafflingly fast pace — taking shape just 500 million years after the Big Bang.

The James Webb Space Telescope has discovered a group of galaxies from the dawn of the universe that are so massive they shouldn't exist.

The six gargantuan galaxies, which contain almost as many stars as the Milky Way despite forming only 500 to 700 million years after the Big Bang, have been dubbed "universe breakers" by the team of astronomers that spotted them.

That's because, if they're real, the discovery calls our entire understanding of galaxy formation into question.

Related: James Webb telescope reveals the 'bones' of a distant galaxy in stunning new image

"It's bananas," co-author Erica Nelson, an assistant professor of astrophysics at the University of Colorado Boulder and one of the researchers who made the discovery, said in a statement. "You just don't expect the early universe to be able to organize itself that quickly. These galaxies should not have had time to form."

Scientists don't know exactly when the first clumps of stars began to merge into the beginnings of the galaxies we see today, but cosmologists previously estimated that the process began slowly taking shape within the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang. Currently accepted theories suggest that 1 to 2 billion years into the universe's life, these early protogalaxies reached adolescence — forming into dwarf galaxies that began devouring each other to grow into ones like our own.

Because light travels at a fixed speed through the vacuum of space, the deeper we look into the universe, the more remote light we intercept and the further back in time we see. By using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to peer roughly 13.5 billion years into the past, the astronomers found that enormous galaxies had already burst into life very quickly after the Big Bang, when the universe was just 3% of its current age.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers say the galaxies are so massive, they are "in tension with 99 percent of the models for cosmology." This means that either the models need to be altered, or scientific understanding of galaxy formation requires a fundamental rethink.

"The Milky Way forms about one to two new stars every year," Nelson said. "Some of these galaxies would have to be forming hundreds of new stars a year for the entire history of the universe. If even one of these galaxies is real, it will push against the limits of our understanding of cosmology."

Right now, all evidence points to these celestial objects being galaxies, but the astronomers haven't ruled out that some of them could be enormous quasars or supermassive black holes.

"This is our first glimpse back this far, so it's important that we keep an open mind about what we are seeing," co-author Joel Leja, an assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics at The Pennsylvania State University, said in a statement. "While the data indicates they are likely galaxies, I think there is a real possibility that a few of these objects turn out to be obscured supermassive black holes. Regardless, the amount of mass we discovered means that the known mass in stars at this period of our universe is up to 100 times greater than we had previously thought. Even if we cut the sample in half, this is still an astounding change."

Previous imaging of the early universe by the Hubble Space Telescope didn't detect the giant galaxies, but JWST is about 100 times more powerful than Hubble.

The $10 billion JWST launched to a gravitationally stable location beyond the moon's orbit — known as a Lagrange point — in December 2021. The space observatory was designed to read the earliest chapters of the universe's history in its faintest glimmers of light — which have been stretched to infrared frequencies from billions of years of travel across the expanding fabric of space-time.

The astronomers say their next step will be to take a spectrum image of the giant galaxies — providing them with accurate distances and a better idea of the chemical makeup of the anachronistic monsters hiding at the beginning of the universe.

The findings were described Feb. 22 in the journal Nature.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.