Biden to reveal first James Webb Telescope image today. Here's what to expect.

The image will offer a view up to 13 billion years into our universe's past

President Joe Biden will reveal the first full-color image from the James Webb Space Telescope today, and it will be the deepest and highest resolution image of the universe ever captured.

Dubbed the "Webb's First Deep Field," the image will offer a view that peers up to 13 billion years into our universe's past, obtained from the faint, gravitationally warped light of ancient galaxies. The image, to be unveiled by the President today (July 11) at 5:00 p.m. EDT (2100 GMT), is one of five images taken by the telescope that are slated for public release on Tuesday (July 12) at 10:30 a.m. EDT (1430 GMT).

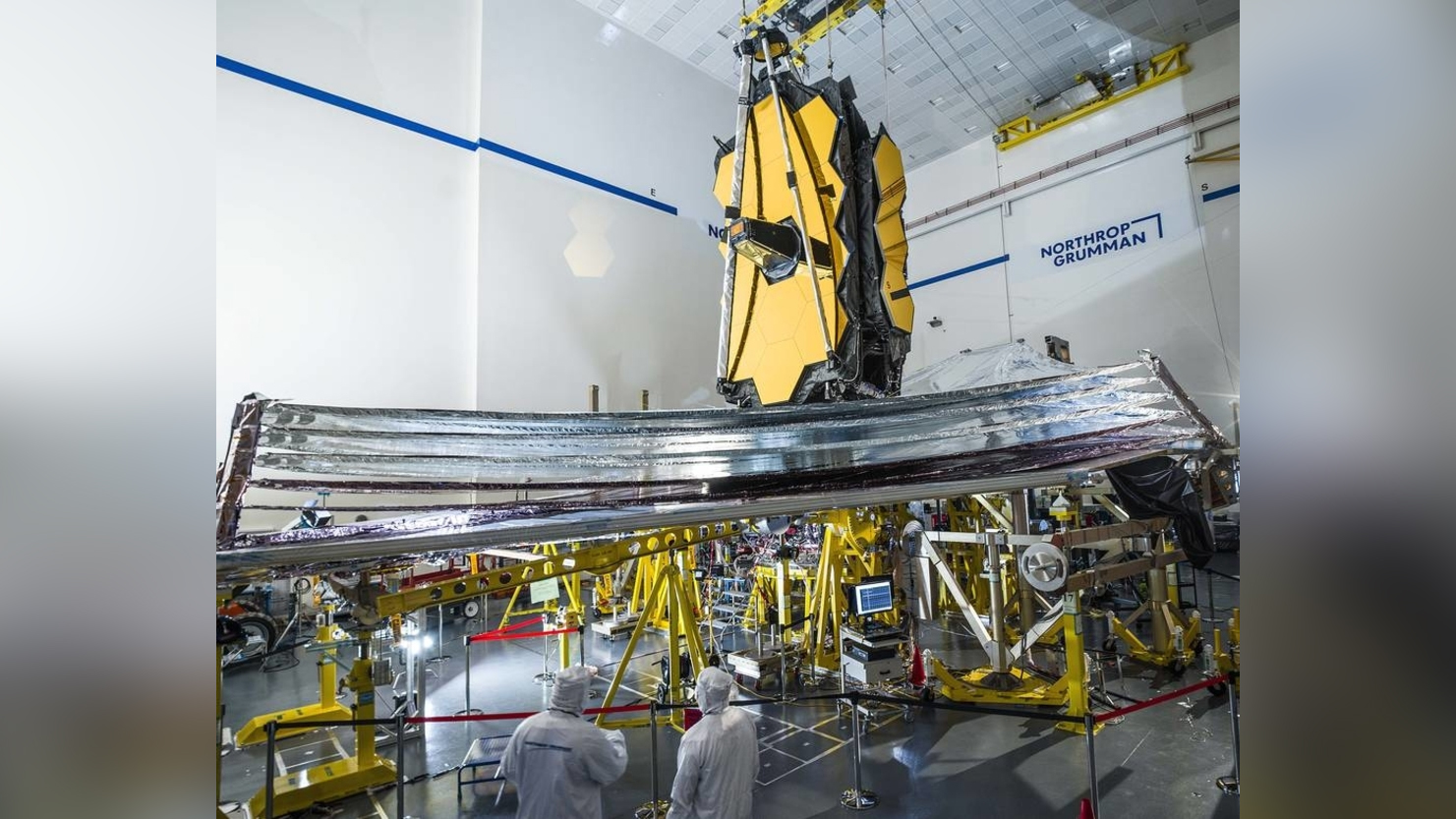

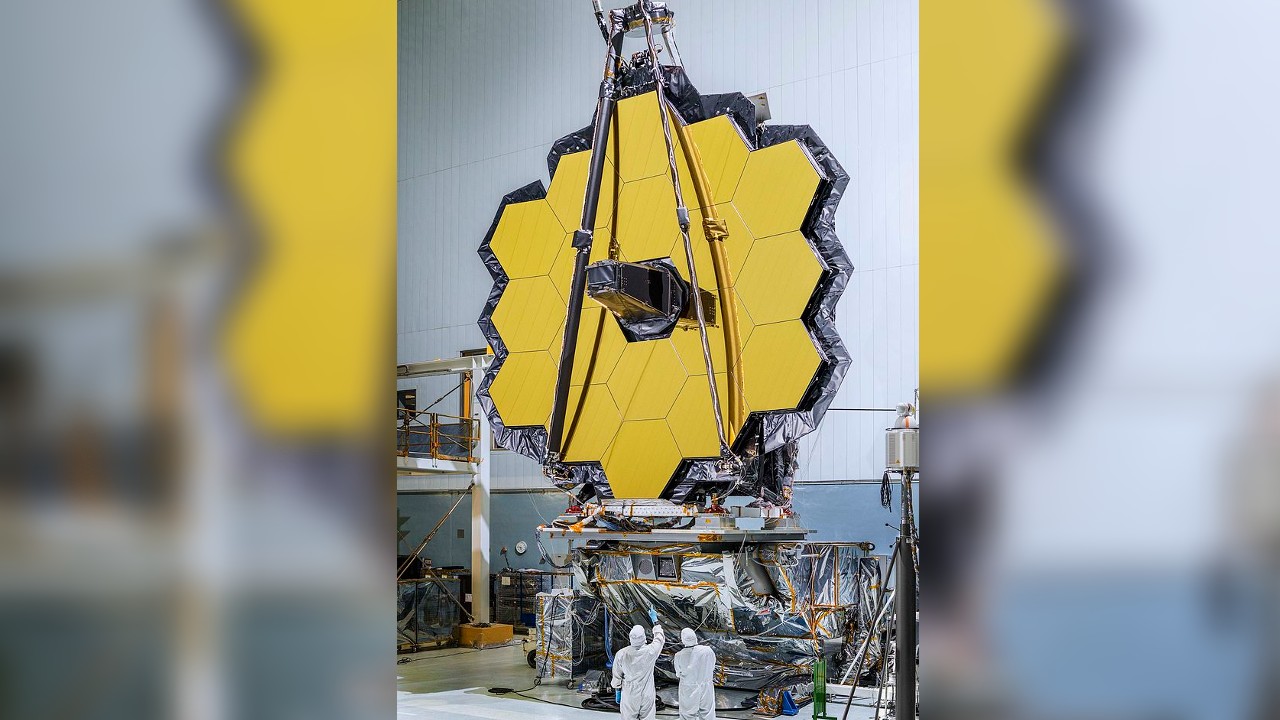

About 100 times more powerful than the Hubble Space Telescope, the $10 billion space observatory was launched to a gravitationally stable location beyond the moon's orbit — known as a Lagrange point — in December 2021. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is the most advanced space telescope ever built, with the ability to peek inside the atmospheres of far-away exoplanets and read the earliest chapter of the universe's history in its faintest glimmers of light — which have been stretched to infrared frequencies from billions of years of travel across the expanding fabric of space-time. Six months of painstaking setup and calibration have seen the telescope's instruments and its 21-foot-wide (6.5 meter) diameter gold-plated mirror readied for operation (its progress was briefly interrupted after receiving a frightening, but thankfully non-damaging hit from a micrometeoroid sometime between May 23 and May 25).

Related: James Webb telescope reaches 'perfect' alignment ahead of debut science images

Now, JWST's first batch of spectacular images are just a day from release, and the handful of scientists who were given a sneak preview say they have been blown away.

"What I have seen moved me, as a scientist, as an engineer, and as a human being," NASA's deputy administrator, Pam Melroy, said in a June 29 press conference.

A NASA teaser, released Friday (July 8), revealed that the highly-anticipated images from the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope will not only take viewers on a tour of the stars but also introduce them to a distant gas planet, the dust-strewn nurseries where stars and planets are born, and two collections of galaxies — one of which will be the deepest and earliest snapshot of the universe's past ever taken.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The five cosmic targets of the images contained in tomorrow's release — picked by an international committee of representatives from NASA, the European Space Agency, the Canadian space agency and Baltimore's Space Telescope Science Institute — have been carefully selected to highlight the diverse capabilities of the new telescope.

The image President Biden will unveil will be of SMACS 0723, a massive foreground cluster of galaxies with a gravitational pull so powerful that it warps both space-time and the path that light subsequently travels through it. This warping effect means that the foreground galaxy acts as a gigantic magnifying lens for fainter light behind it that is more distant — and therefore older. By studying this light, which left its source soon after the universe formed, scientists hope to learn more about the beginnings of the cosmos, and possibly even catch a glimpse of the elusive photons that came from the very first stars to ever exist. Though the JWST will seek out diverse cosmic targets, it is the hunt for this light that inspired the telescope's designers to build it.

Another soon-to-be-released image of mind-bending galactic proportions will be a quintet of five galaxies of which four are "locked in a cosmic dance of repeated close encounters," according to the NASA teaser. Studying the chaotic orbit of planets in these galaxies, known as "Stephan's Quintet," could give scientists some important insights into how gravity behaves at very large scales. It could also provide clues into the nature of dark matter — the mysterious cosmic glue that has never been directly detected but is thought to make up most of the universe's mass.

Related: In a historic launch, the Webb Telescope blasts off into space

The subject of another image is the Carina Nebula, a dust and gas cloud that is 7,600 light-years from Earth, measures 50 light-years wide, and is one of the brightest and most active star-forming regions ever discovered. It is home to many stars much larger than our sun; one of them, Eta Carinae, underwent an enormous explosion that began in 1837. The star briefly became the second brightest object in the night sky, eventually transforming into the Homunculus Nebula. Studying this region could give scientists some crucial insights into the beginnings of our solar system's life, and may predict its spectacular finale.

The fourth snapshot will be the first full-color spectrum of WASP-96b, a giant, mostly gaseous exoplanet that's half the mass of Jupiter and is located nearly 1,150 light-years from Earth. First discovered in 2014, WASP-96b is so close to its sun that a single solar orbit takes just 3.4 Earth days.

This proximity to its star also means the exoplanet is scorchingly hot and highly unlikely to harbor life, but scientists are nonetheless hoping to use the inhospitable gas giant as a testing bed for the telescope's life-finding capabilities.

Like other space telescopes, the JWST can detect the atmospheric compositions of distant planets through a method known as the transit technique. When a planet passes in front of its star, light from the star is absorbed and later reemitted by molecules in the planet's atmosphere, giving off certain signatures depending on which molecules are present. If these signatures indicate the presence of methane or carbon dioxide, that could hint at the presence of alien life. And unlike NASA's Hubble and Spitzer Space telescopes, the JWST can detect possible transit signatures across a much wider range of the light spectrum, enabling it to perform more comprehensive atmospheric scans.

The last of the images features the Southern Ring Nebula, also known as the "Eight-Burst" for its figure-eight appearance. Positioned around 2,000 light-years from Earth, the nebula is an expanding cloud of gas and dust that a red dwarf star shed during its death throes . As the nebula's dust particles are particularly rich in heavy elements such as carbon, these remnants could one day go on to form new stars and planets, making the nebula a fascinating study subject for exploring the cosmic cycle of death and rebirth.

While the images are intended primarily to showcase what the JWST can do, rather than be studied themselves, they provide a first glimpse of the telescope's remarkable capabilities and hint at groundbreaking discoveries to come. After applying through a competitive process, scientists have already booked the telescope's first year of observations to study diverse cosmic topics, such as the origins of supermassive black holes; the temperature of dark matter; how planets get their water; the baffling inconsistency of the universe's measured rate of expansion; and how the first stars formed.

"The James Webb Space Telescope will give us a fresh and powerful set of eyes to examine our universe," Eric Smith, a program scientist at NASA, wrote in a blog post. "The world is about to be new again."

You can watch Biden's unveiling of the JWST's First Deep Field at 5:00 p.m. EDT on NASA TV and view the image simultaneously on NASA's website.

The release of the remaining four images will take place on July 12 at 10:30 a.m. EDT, and you can follow that here at Live Science or on NASA's website. NASA Science Live will host an additional Q&A event on July 13 at 3 p.m. EDT (1900 GMT), to answer questions about the new images.

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.