Jousting: Origins and history of the medieval sport

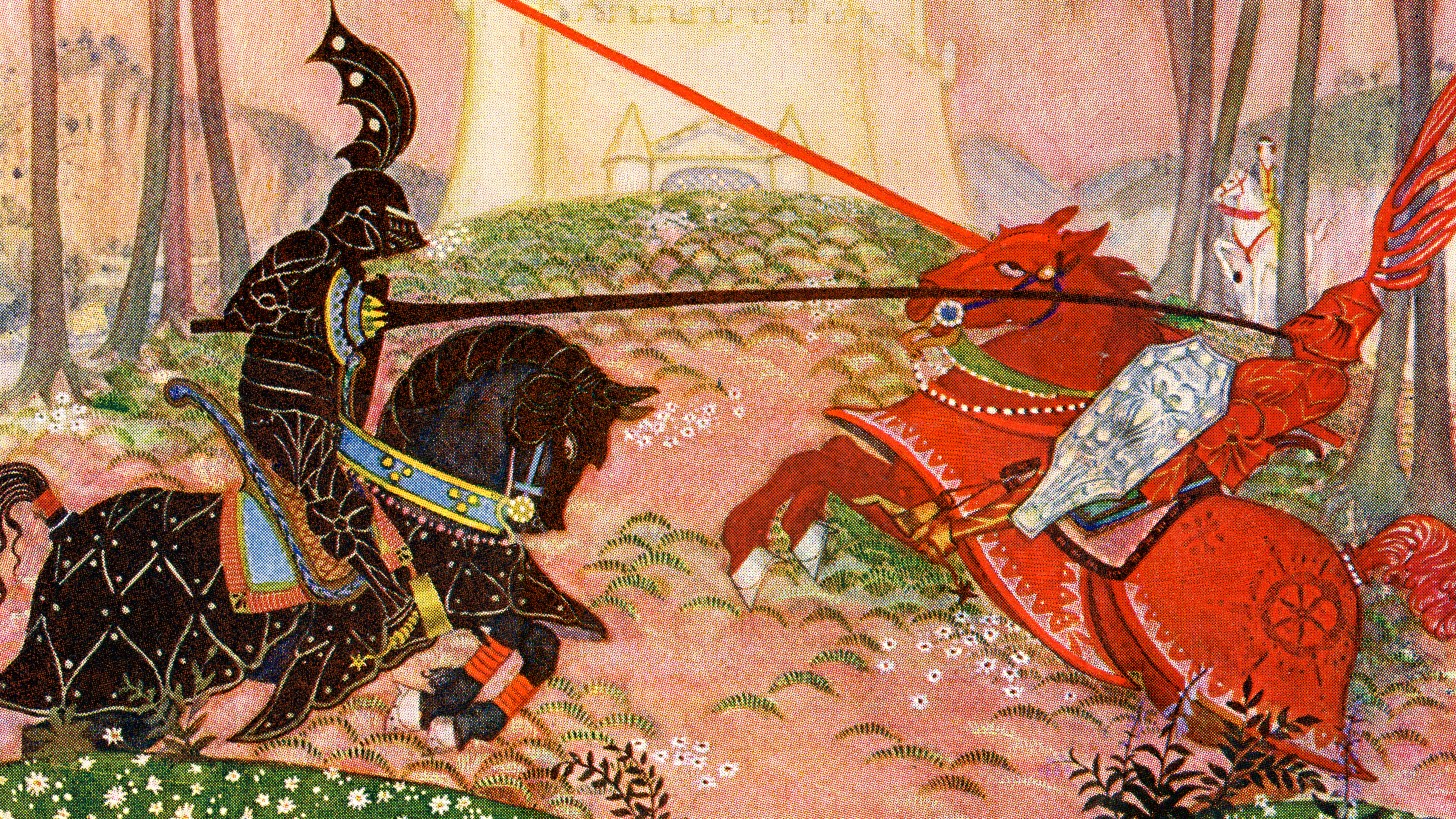

Jousting was a medieval tournament that saw knights compete against each other on horseback.

Jousting was the main event of tournaments that were seen throughout much of Europe during the medieval period and beyond. Warriors have practiced for war since ancient times, but the tournament as it later became known first emerged in north-west France, in the late 11th-century.

Mounted contests known as jousts became very popular during the 13th century and eventually became the most popular spectacle. Though competing knights wore thick armour to protect their head and torso, jousting remained a dangerous sport. causing injury and even death.

Origins of jousting

In the early tournaments, hundreds of knights fought in two teams in open countryside, often supported by footsoldiers. The name is probably first mentioned in 1114 and comes from the turning or wheeling maneuvers involved, according to David Crouch in his book "Tournament" (Hambledon and London, 2005). The aim was to capture opposing knights for ransom and as well as providing good training it was a way to make money.

Individual combats with lances were called jousts, probably from the Latin juxtare, "to meet together" and Middle French joster, "to encounter." They sometimes took place at this period before the main battle, reflecting real life when champions challenged each other between two armies. The earliest reference is in the preliminary jousting before a tournament at Tournai in 1095, when Count Henry of Brabant was killed, according to Crouch.

The popularity of jousting grew during the first half of the 13th century, partly because of royal bans on the team tournaments, first in England and then in France. Initially they were often part of Round Tables, which were gatherings that alluded to King Arthur. It may also owe "much to the numerous descriptions in literature of judicial duels (usually between a hero and a villain)," writes Maurice Keen in his book "Chivalry" (Yale University Press, 1984).

Jousting also allowed participants to show off their skills in front of other jousters and also spectators, without being attacked by several others. They included more parading and pageantry and the growing influence of chivalry was reflected in the participation of ladies, jousters sometimes carrying their token, or favor. The German Ulrich von Liechtenstein supposedly rode on his jousting tour of the Holy Roman Empire in 1226 dressed as Lady Venus, recall Richard Barber and Juliet Barker in "The Tournament" (The Boydell Press, 1989).

The Burgundian dominions of the Low Countries "were also the home of the bourgeois tournament", writes Keen.

How were jousting lances made?

Lances appear to have been often made of ash wood, although Geoffrey Chaucer mentions cedar wood, say David Edge & John Miles Paddock "Arms and Armour of the Medieval Knight" (Bison Books Ltd, 1988). Two Tudor lances in the Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds, England, are made from pine and probably fir.

The lance was about 12 feet (3.6m) long and during the 14th century was increasingly furnished with a circular steel vamplate to protect the hand. Behind this was a ring around the shaft that tucked into the armpit to prevent the lance slipping backwards on striking the opponent. This ring developed into the graper, a crown of small spikes that bit into a wooden core held in a ‘lance rest’ on the steel breastplates of armor from the 15th century onwards.

For jousts of war , a sharp steel head was used, to demonstrate courage and skill.or jousts during peacetime, a blunted head was used or else a steel coronel of small prongs that spread the force of the blow.

In the 15th century lances lengthened to about 14 feet (4.27m), according to Miles and Paddock. These were larger in front of and behind the hand, and tapered in shape at both ends. By the Early Modern period jousting lances had generally shortened and were fluted on the outside. They were sometimes hollow inside or jointed so they would shatter more easily.

Did jousts end in a fight to the death?

Many jousts were run to show off skill and win points. Despite blunted weapons increasingly being used, accidents happened. In 1252 at Walden, England, a knight was killed when a sharp lance was used by mistake, according to Crouch. Sometimes foul play was suspected. In other contests tempers sometimes boiled over.

Jousts with sharp lances were obviously more dangerous: Barber and Barker describe how in 1438 in Paris John Astley ran Piers de Massy through the head with his lance, killing him. Such jousts were favored during truces such as between England and Scotland or France.

In the 14th and 15th centuries challenges to duels with sharp weapons were sent out during peacetime, often to fulfil a vow; Lord Scales had a gold chain with a forget-me-not tied round his leg by the English ladies as sign of his vow, writes Keen.

It is easy to confuse jousting to win renown with the judicial duel, a combat fought in the presence of the church to settle a dispute between two persons. It was believed that God would give victory to the man who was in the right. For those of rank it was fought in full armor on horseback and it continued until one of the combatants was killed or yielded.

How dangerous was jousting?

Jousting was dangerous: with the two horses coming together at speeds of around 50-60 miles per hour per hour (80-96 kilometers per hour) . A central dividing barrier, known as a tilt, is not mentioned until 1429 and even after that some contests were still run in the open fieldso colliding, or damaging the knees from passing too closely, was a real danger.

At Le Hem in France in 1278 two jousters rode "so close that they crashed together, chest to chest, both man and horse", recounts an eyewitness in Nigel Bryant’s translation in "The Tournaments at Le Hem and Chauvency (The Boydell Press, 2020).

From the 14th century special armor pieces began to be appear, the first being the helm, which Edge and Paddock describe as becoming frog-mouthed: the lower edge of the eye-slit began to jut forward like the prow of a ship, to deflect a lance and help protect against the splinters of wood that flew everywhere if the lance shattered.

Once solid breast and back plates began to be worn during the later 14th century, the helm could be strapped or stapled down to prevent it being snapped back from the impact of a lance. Later helms had a web of adjustable laces and straps inside attached to a padded hood to hold and cushion the head. The jousting shield could be laced to the breastplate and a large gauntlet called the manifer protected the left hand.

From the 15th century onwards, jousting armor became thicker and heavier and some courses involved extra pieces called ‘reinforces’ for the left side: the elbow (pasguard) and shoulder and throat (grandguard), which meant the shield could be left off. Manifer, pasguard and grandguard overlapped upwards so as not to catch a lance point. On Henry VIII’s 1540 armor a spare set was to hand in case of damage, notes Ian Eaves in his article "The Tournament Armours of King Heny VIII of England" (Livrustkammaren, Journal of the Royal Armoury, 1993).

Despite all these safeguards it could still be lethal, as Henry found out. "Twice, in 1524 and 1536, his love of jousting brought him within inches of death - even for kings it was a dangerous sport", remarks Thom Richardson in his book "The Armour & Arms of Henry VIII" (Royal Armouries Museum, 2002).

Henri II of France died in 1559 when a splinter of lance pierced his eye-slit and Charles IX was seriously injured in 1561, which largely contributed to the decline in jousting in France, according to Zeev Gourarier in his article "From the game of ‘catching the brass ring’ to the roundabout" (Livrustkammaren, Journal of the Royal Armoury, 1991-2).

Violent impacts could result in strained or broken backs or limbs, piercing wounds or bad falls despite the thickly sanded lists (the jousting arena). King Duarte of Portugal’s treatise of about 1434 advises that, even in training, progress "from light to heavy lance must be gradual to avoid the risk of rupture, back-ache, headache, or pains in the legs and hands", says Sydney Anglo in his article "Jousting- the earliest treatises" (Livrustkammaren, Journal of the Royal Armoury, 1991-2).

Jousting rules

The Statute of Arms of 1292 shows that some rules were in use in England for the tournament and tried to reduce unruly behavior especially by squires and spectators. Barber and Barker assert that actual rules only survive from the 15th century onwards "and it is all too easy for these to influence our view of what went on in earlier tournaments."

Several runs would be agreed, perhaps followed by sword combat on foot. During the 15th century we see lavish spectacles such as the pas d’armes, in which several knights held a piece of ground against all comers. Detailed challenges could be sent out sometimes as much as a year ahead. The various agreed combats might be represented by the defendants' colored shields, a challenger selecting one by tapping it. Many different types of joust arose in different countries, run with or without a barrier.

Heralds recorded names and scores, unhorsing obviously winning most points. Striking coronel to coronel was very difficult and striking the helmet crest noteworthy; breaking your lance cleanly on your opponent also earned points. "There are a number of prohibited attaints", points out Anglo, "hitting the head or neck of the opponent’s horse, his saddle-bow, bridle hand, thigh or any place below it." The survival of later scoresheets, called cheques, gives an insight.

"Statistics derived from these figures show that fifty to sixty five percent of the lance courses run did not score a hit on either side," says Claude Gaier in his article "Arms and Armour used in Lists Contests in the Bungundian Principalities during the XVth Century" (Livrustkammaren, Journal of the Royal Armoury, 1993).

Later surviving rules also highlight a man's credentials for taking part. "Lack of hereditary qualification, or marriage below one’s estate, were the commonest ‘reproaches’ against would be jousters", writes Maurice Keen.

When did jousting end?

Jousting continued into the 16th century as an elaborate spectacle. Henry VIII was a lifelong sportsman and in Germany Emperor Maximilian had invented many runs including some to heighten excitement as safety increased; these included shields on springs that burst into fragments when struck and one joust run without body armor except for a chest plate, coffins being brought into the lists!

The elaborate pas d’armes and specialized armor increasingly separated jousting from real war, yet great jousters were often adept at both. However, by the end of the 16th century warfare was changing. Lances were ineffective against bodies of infantry with pikes backed up by musketeers, this being reflected in the tournament where groups fought with pikes over a barrier in the foot tourney. Some jousts continued into the early 17th century but were replaced by the carrousel, which emphasized horsemanship and display.

The disappearance of armor from the battlefield in the late 17th century now made it hugely expensive, say Barber and Barker. Tilting at the quintain (a dummy) or a dummy head and spearing a hanging ring survived into the 19th century (the latter still Maryland’s ‘Official State Sport’). In 1778 a tournament was held by Lord Cathcart in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, recounts Walter J. Karcheski, Jr in "Combats of Columbia: American Tournaments up to the Atlantic City Horse Show of 1935" (Livrustkammaren, Journal of the Royal Armoury, 1991-2). The 19th-century medieval revival saw the Eglinton tournament in Ayrshire, Scotland, in 1839, although the British weather nearly ruined the proceedings. Jousting is seen in films and on TV both accurately and inaccurately and has been re-enacted by enthusiastic groups of modern knights and squires. Hopefully it will live on.

Additional Resources

The Royal Armouries, Leeds has a large collection of Jousting armor, a great deal of which can be viewed on their site. Sudeley Castle and Gardens has an interesting article containing 9 things you may not have known about jousting which can be found here. Finally, Juliet Barker's "The Tournament in England, 1100-1400," (The Boydell Press, 2003) is an excellent work on the history of the English Tournament.

Bibliography

- David Crouch "Tournament" (Hambledon and London, 2005)

- Maurice Keen "Chivalry" (Yale University Press, 1984)

- Richard Barber and Juliet Barker "The Tournament" (The Boydell Press, 1989)

- David Edge & John Miles Paddock "Arms and Armour of the Medieval Knight" (Bison Books Ltd, 1988)

- Nigel Bryant "The Tournaments at Le Hem and Chauvency" (The Boydell Press, 2020)

- Ian Eaves "The Tournament Armours of King Henry VIII of England" (Livrustkammaren, Journal of the Royal Armoury, 1993).

- Thom Richardson "The Armour & Arms of Henry VIII" (Royal Armouries Museum, 2002)

- Zeev Gourarier "From the game of ‘catching the brass ring’ to the roundabout" (Livrustkammaren, Journal of the Royal Armoury, 1991-2)

- Sydney Anglo "Jousting- the earliest treatises" (Livrustkammaren, Journal of the Royal Armoury, 1991-2)

- Claude Gaier "Arms and Armour used in Lists Contests in the Bungundian Principalities during the XVth Century" (Livrustkammaren, Journal of the Royal Armoury, 1993)

- Walter J. Karcheski, Jr "Combats of Columbia: American Tournaments up to the Atlantic City Horse Show of 1935" (Livrustkammaren, Journal of the Royal Armoury, 1991-2)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Christopher Gravett is a former senior curator at the Royal Armouries of the Tower of London. He is now an historical consultant, and the author of "The Medieval Knight", (Osprey Publishing, 2020) and "Bosworth 1485" (Osprey Publishing, 2021) among a number of other works on the subjects of knights and medieval warfare.