Jupiter will be at its closest to Earth today (Sept. 26) in 59 years

Despite occurring on similar time scales, Jupiter's opposition and its perigee very rarely coincide, making this a rare unmissable chance to view the massive planet.

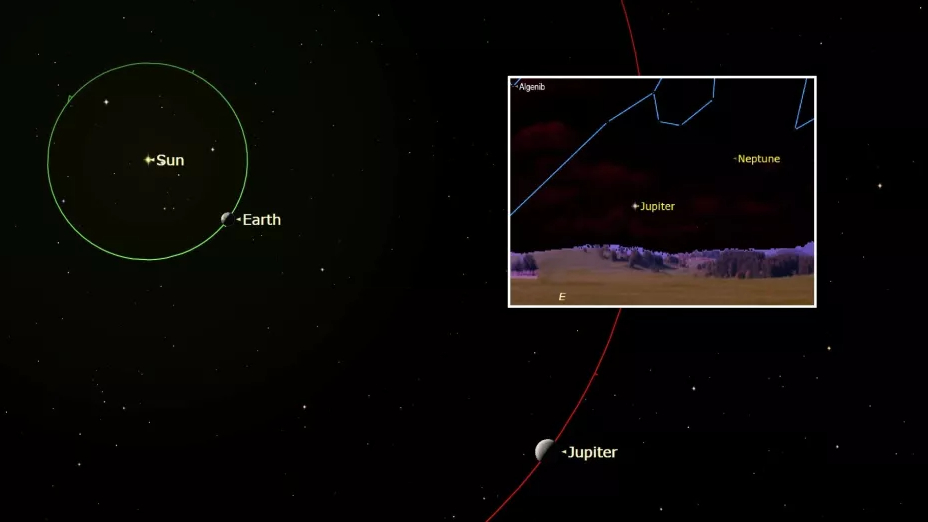

Jupiter will be directly opposite the sun as seen from Earth on Monday (Sept. 26), allowing skywatchers to see the solar system's largest planet in incredible detail during an event known as opposition.

During the opposition Jupiter, Earth, and the sun are aligned in such a way that both planets are on the same side of the star with Earth sitting between these two massive bodies. As the gas giant reaches opposition while rising from the east at the same time the sun sets in the west, it will also be at its closest approach to Earth , known as perigee. This closest approach will bring Jupiter to around 367 million miles from Earth, the gas giant's closest to our planet since 1963.

During opposition the planet will be in the Pisces constellation and be visible for most of the night, rising when the sun sets and disappearing when the sun rises. You can watch an online webcast of Jupiter at opposition on Tuesday (Sept. 27) beginning at 4:30 p.m. EDT (2030 GMT) thanks to the Virtual Telescope Project.

Related: Jupiter is at its closest to Earth in 59 years, NASA says

According to In-The-Sky.org, Jupiter will be visible overnight from New York between 7:33 p.m. EDT (2333 GMT) on Sept. 26 and 06:08 a.m. (1008 GMT) on Tuesday (Sept. 27). The planet will appear from an altitude of 7 degrees above the eastern horizon moving to 49 degrees above the southern horizon (its highest point ) at 12:51 a.m. EDT (0451 GMT) on Tuesday (Sept. 27) morning before sinking below the western horizon. For skywatchers living in New York City, The Gothamist has collected some tips on how to view the planet from NYC specifically.

Wherever you happen to be, the best way to see Jupiter in opposition will be with binoculars or a telescope from a dark and dry area with high elevation. Good binoculars should be enough to see the banding across the center of the gas giant and even some of its larger moons. Viewing with a large telescope should allow the planet's 'Great Red Spot — a storm so wide it could swallow two Earths side-by-side.

Despite occurring on similar time scales, Jupiter's opposition and its perigee very rarely coincide, making this a rare unmissable chance to view the massive planet. Jupiter moves in opposition roughly every 13 months at which time it is larger and brighter in the sky than usual.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As Earth takes its 365-day orbit around the sun, it also makes its closest approach to Jupiter once every 12 months; Jupiter's orbit around our star takes 12 times as long to complete.

While the separation of over 350 million miles between Earth and the gas giant which may seem anything but 'close,' the greatest distance between our planet and Jupiter is around 600 million miles (960 million km).

Jupiter is about 484 million miles (778 kilometers) from the sun, over five times the average distance between the Earth and the star. This massive distance from the sun means that Jupiter’s close approach will only make a small difference to its size in the night sky.

If you miss Jupiter at opposition this year, the next chance to see this astronomical event will be on Nov. 3, 2023.

Whether you're new to skywatching or have been it at for years, be sure not to miss our guides for the best binoculars and the best telescopes to spot Jupiter and other celestial wonders. For capturing the best Jupiter pictures you can, check out our recommendations for the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Originally published on Space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. who specializes in science, space, physics, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, quantum mechanics and technology. Rob's articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University