Jurassic squid got murdered mid-meal, leaving this epic fossil behind

This was the ultimate Jurassic seafood platter.

During the early Jurassic period, a squid-like creature was in the midst of devouring a crustacean, when it was interrupted by another marine beast, possibly a shark, that chomped into its squishy side and killed it, a new study finds.

The shark swam away, but the crustacean and the squid-like animal — a 10-armed and two-finned creature called a belemnite — sank to the bottom of the sea, where they fossilized together over the subsequent eras in what is now Germany.

The resulting 180 million-year-old fossil is "unique," one of about "10 specimens of belemnites with [well-preserved] soft tissues worldwide," study lead researcher Christian Klug, curator of the University of Zurich's Palaeontological Museum and a professor at its Palaeontological Institute, told Live Science in an email.

The specimen also shows how predators sometimes become prey themselves. "Predators tend to be happy when they are eating, forgetting to pay good attention to their surroundings and potential danger," Klug said. "That might explain why the belemnite got caught, but there is no proof for that."

Related: Image gallery: Photos reveal prehistoric sea monster

The fossil also inspired a new term: pabulite, from the Latin words "pabulum" and "lithos," which mean "food" and "stone," respectively. Palubite refers to meal "leftovers" that never enter the predator's digestive system and later fossilize — in this case, that leftover would be the belemnite, the researchers wrote in the study.

A pabulite can "provide evidence for incomplete predation," which is likely what happened here, the researchers wrote in the study. In fact, it's possible that the shark purposefully targeted the belemnite's squishy parts, rather than its pointy hard tip, known as the rostrum. Vertebrate predators likely learned to avoid the hard-to-digest rostra, and as a result may have "bit off the soft parts, which were poorly protected," the researchers wrote in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Remarkable" specimen

Amataur fossil collector Dieter Weber discovered the specimen in 1970 in a small quarry near Holzmaden, a small village near Stuttgart in southwestern Germany. Study co-researcher Günter Schweigert, curator of Jurassic and Cretaceous invertebrates at the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart (SMNS), saw the specimen in 2019 while visiting Weber's collection, and SMNS purchased it soon after.

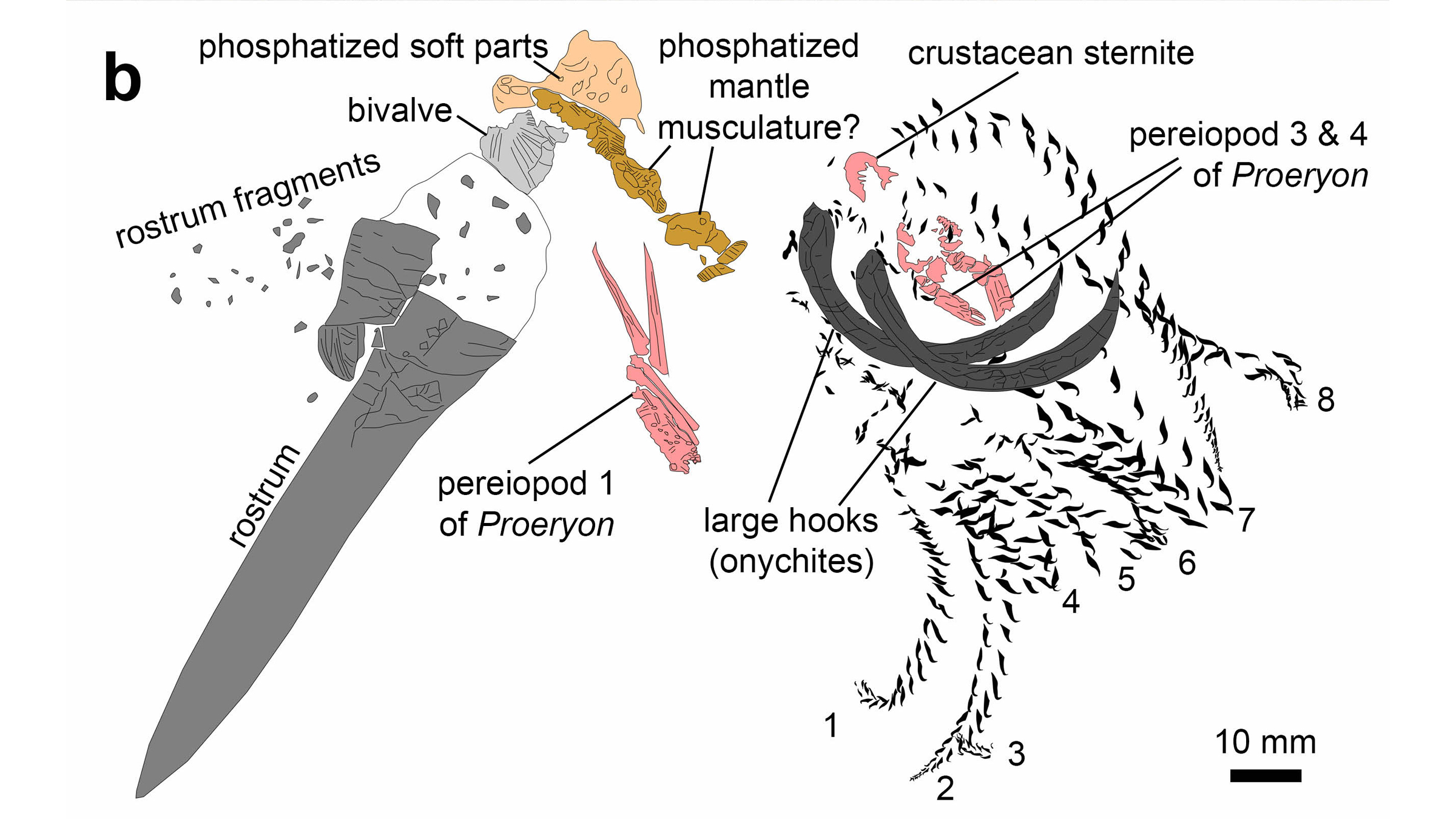

Researchers immediately got to work studying the specimen. The belemnite, they discovered, was the well-known species Passaloteuthis laevigata, whose fossilized remains have been found in Europe and Morocco in rocks dating to the Toarcian age (183 million to 174 million years ago). P. laevigata was a small creature, with a nearly 4-inch-long (9.3 centimeters) bullet-shaped rostrum; each of its 10 arms were up to 3.5 inches (9 cm) long and carried double rows of arm-hooks. These hooks, 400 in all, would have helped P. laevigata grip slippery prey, Klug said.

"In this individual, two arms were modified, bearing large hooks," Klug noted, "We guess that these were used for mating and possibly only males had them, while in females, all 10 arms were similar, but we have no proof for that yet."

Belemnites are now extinct, but fossils reveal that they had an internal shell surrounded by muscles and skin, Klug said. These strong horizontal swimmers actively preyed on sealife, including fish and crustaceans, and in turn were eaten by sharks and dolphin-like predators known as ichthyosaurs, he said.

So, it's no surprise that this belemnite was chomping on a crustacean from the genus Proeryon, which had a broad and flat lobster-like body and long, slender claws, Klug said. However, the Proeryon was poorly preserved, so "we think that these are remains of an old skin (a molt)," he wrote in the email. "Crayfish remove much of the calcium from the shell before they molt, because they later put it into the new skin."

Related: Release the kraken! Giant squid photos

Cephalopods (a group that includes octopuses, squid and nautiluses) "do love to eat this old skin," Klug added. "Much of it is lying really between the arms of the belemnite, quite close to its mouth, so it is likely that the belemnite was actually feeding on it."

Although parts of the belemnite are well preserved, including its rostrum and arms, much of its body is missing. This is why "we must conclude that a larger predator ate most of the belemnite," Klug said.

What ate the belemnite?

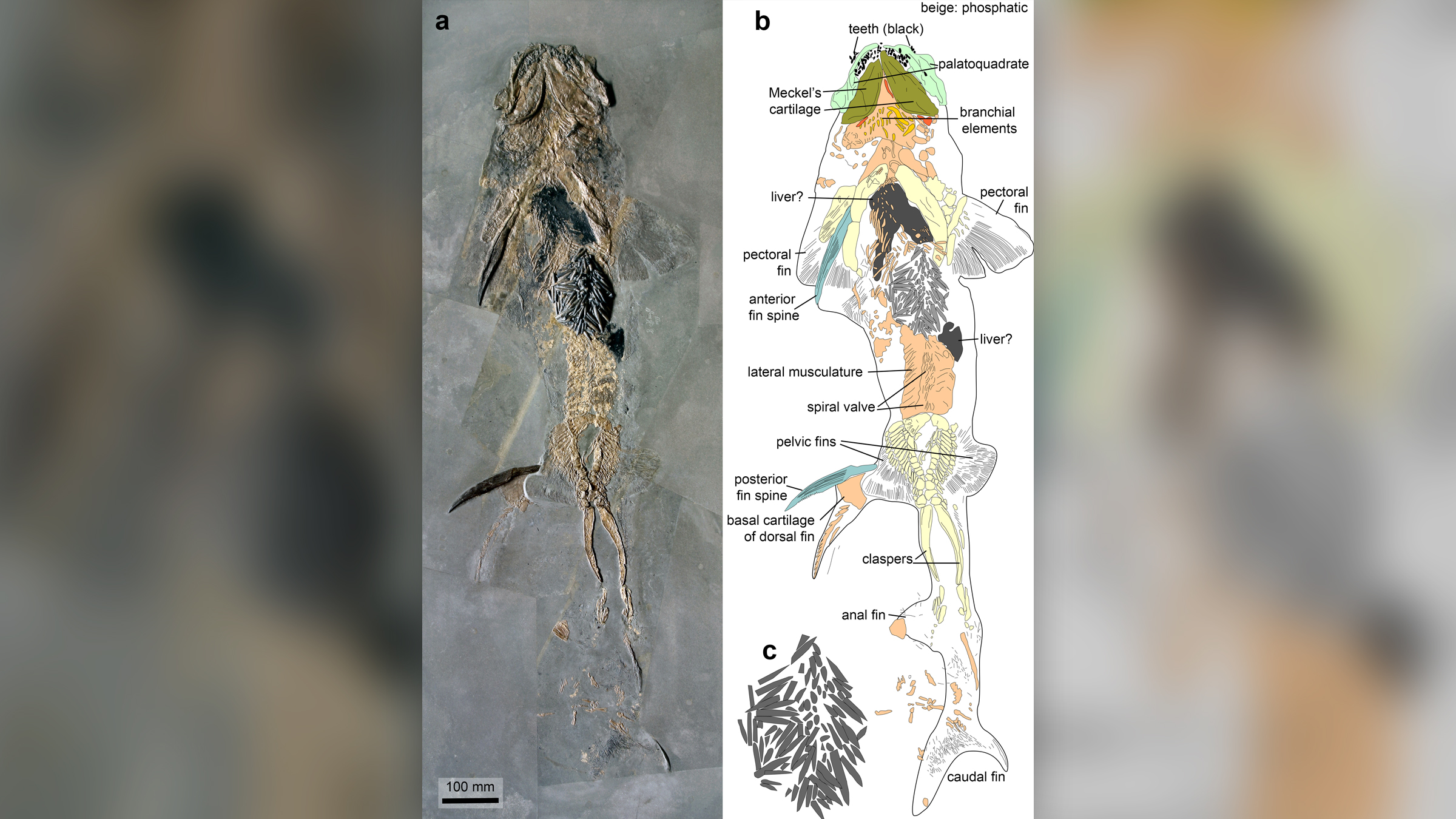

A prime candidate for the belemnite's "killer" is the early Jurassic shark Hybodus hauffianus. A previously described H. hauffianus fossil was stuffed with belemnite remains, including dozens of rostra.

That particular H. hauffianus "possibly ran into a swarm of belemnites and got too enthusiastic about it: It ate about 200 of them but forgot to bite off the rostra, thereby clogging its stomach, which eventually killed it," Klug said.

Other suspects include large predatory fish, such as Pachycormus and Saurorhynchus, the marine crocodile Steneosaurus, and the ichthyosaur Stenopterygius, whose fossilized stomach remains contain belemnite mega-hooks, the researchers wrote in the study.

The study was published online April 29 in the Swiss Journal of Palaeontology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.